George Westinghouse

George Westinghouse | |

|---|---|

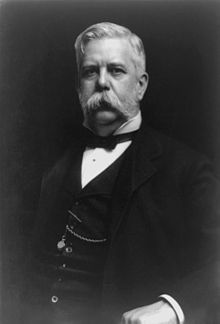

Westinghouse in 1884 | |

| Born | October 6, 1846 Central Bridge, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 12, 1914 (aged 67) New York City, U.S. |

| Known for | Founder of the original Westinghouse Electric Corporation, the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, and others |

| Spouse |

Marguerite Erskine Walker

(m. 1867) |

| Children | 1 |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

George Westinghouse Jr. (October 6, 1846 – March 12, 1914) was a prolific American inventor, engineer, and entrepreneurial industrialist based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He is best known for his creation of the railway air brake and for being a pioneer in the development and use of alternating current (AC) electrical power distribution. During his career, he received 362 patents for his inventions and established 61 companies, many of which still exist today.

His invention of a train braking system using compressed air revolutionized the railroad industry around the world. He founded the Westinghouse Air Brake Company in 1869.[1] He and his engineers also developed track-switching and signaling systems, which lead to the founding of the company Union Switch & Signal in 1881.

In the early 1880s, he developed inventions for the safe production, transmission, and use of natural gas. This sparked the creation of a whole new energy industry.

During this same period, Westinghouse recognized the potential of using alternating current (AC) for electric power distribution. In 1886, he founded the Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Westinghouse's electric business directly competed with Thomas Edison's, who was promoting direct current (DC) electricity. Westinghouse Electric won the contract to showcase its AC system to illuminate the "White City" at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The company went on to install the world's first large-scale, AC power generation plant at Niagara Falls, New York, which opened in August 1895.

Ironically, among many other honors, Westinghouse received the 1911 Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers "for meritorious achievement in connection with the development of the alternating current system".[2]

Early years

[edit]

George Westinghouse was born in 1846 in the village of Central Bridge, New York (see George Westinghouse Jr. Birthplace and Boyhood Home), the son of Emeline (Vedder) and George Westinghouse Sr., a farmer and machine shop owner.[3] The Westinghouse ancestors came from Westphalia in Germany, moving first to England and eventually emigrating to the US. The family name had been anglicized from Wistinghausen.[4][5]

From his youth, Westinghouse displayed a talent for machinery and business. He was encouraged by his father and was assigned tasks in the Westinghouse Company workshop. The company produced farm equipment such as the Westinghouse Farm Engine.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, the then 14-year-old attempted to run away from home to enlist, but was stopped by his father. In June 1863 his parents allowed him to enlist, first in the 12th Regiment of the New York National Guard and then in the 16th Regiment of the New York Cavalry. He earned a promotion to the rank of corporal before being honorably discharged in November 1863. A month later he joined the Union Navy. He served as an Acting Third Assistant Engineer on the gunboat USS Muscoota and then on the ship USS Stars and Stripes through the end of the war.[6] These ships were used to blockade Southern port cities. After his discharge in August 1865, Westinghouse returned to his family and enrolled at Union College in Schenectady, but he quickly lost interest and dropped out during his first term.[7]

He further developed his skills in his father's company shop. Westinghouse was just 19 when he received his first patent for a rotary steam engine.[8] At age 21, he invented a car replacer, a device used to guide derailed railroad cars back onto the tracks, and a reversible "frog", a rail junction piece used to switch trains between different tracks.[9] In 1868, Westinghouse moved with his wife to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to access better and less expensive steel for the manufacture of his railroad frogs, and there he began to develop his recently invented railroad air brake concept.

Railroad air brakes and signaling/switching systems

[edit]

During his travels, Westinghouse had witnessed the aftermath of a collision where engineers on two trains, approaching each other on the same track, had seen each other but were unable to stop their trains in time due to the existing brake systems. At that time, brakemen had to run along catwalks on the top of the cars, manually applying the brakes. Coordinating that process was tricky and dangerous. It also meant trains could not exceed ten cars in length, and thousands of brakemen died or were maimed each year.[10]

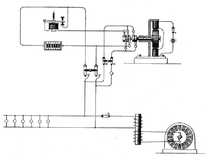

In 1869, at age 23, Westinghouse first publicly demonstrated his revolutionary new railroad braking system in Pittsburgh. It stopped trains using a compressed air system. His first braking system used an air compressor and an air reservoir in the locomotive, with a single compressed air pipe running the length of the train and with flexible connections between cars. That line controlled the brakes, allowing the engineer to apply and release the brakes simultaneously on all cars. A charter for what would eventually become the Westinghouse Air Brake Company was filed in July of that year.

Although the system was successful, as demonstrated when it prevented a serious mishap in front of assembled witnesses,[11] it was hardly fail-safe. Any rupture or disconnection in the air line left the train without brakes. Over the next two years, Westinghouse and his engineers addressed the problem by inverting the process, designing valves so that constant pressure in the lines kept the brakes disengaged. An air reservoir was also placed on each car. With the improved design, any interruption or break in the line automatically caused the train to stop.

During the next decade, building on his earliest inventions, Westinghouse expanded his interest to railway signaling and track-switching systems. Previously, signaling relied on oil lamps and track switching was performed manually. Westinghouse's designs changed all that. In 1882, Westinghouse founded the Union Switch and Signal Company to manufacture, market, install, and maintain these innovative control systems, which were eventually adopted by railroads around the world.[12][13]

Natural gas

[edit]By 1883, Westinghouse had become interested in natural gas. Gas had recently been discovered in nearby Murrysville, Pennsylvania, and it attracted a lot of attention, in part because of a spectacular flaming blowout of the Haymaker Well in 1878. After visiting the well and recognizing its commercial potential, he undertook drilling for gas on his estate Solitude (today's Westinghouse Park) in Pittsburgh.

Early in the morning of May 21, 1884, the drilling crew struck a pocket of gas at a depth of 1500 feet, and the resulting blast of dirt and water blew the top off the derrick. It took Westinghouse a week to devise a method to cap the flow of gas. He was encouraged to develop a system to deliver gas to heat and light area homes and businesses.[15] Eventually, several natural gas derricks towered above his estate's Victorian-era gardens.[14] In modern times there is no above-ground trace left of these derricks.

That year, Westinghouse acquired a dormant utility charter for "The Philadelphia Company", and over the next three years, he developed devices and secured more than 30 patents for this technology. He used the Philadelphia Company to develop gas wells and to promote gas usage both for commercial and residential purposes. By 1886, the Philadelphia Company owned 58 wells and 184 miles of distribution piping in the Pittsburgh area, and by 1887, it served over 12,000 private homes and 582 industrial customers throughout the state.[16]

In 1889, as his involvement with the generation and distribution of electricity was surging, Westinghouse resigned as president of the Philadelphia Company, but he remained on its board. Growth in the natural gas business slowed in the 1890s, hindered by supply problems and ongoing safety concerns related to gas distribution in homes and businesses. However, the Philadelphia Company continued to grow, spawning enterprises such as Equitable Gas and Duquesne Light.

Electric power distribution

[edit]

In the early 1880s, Westinghouse's interest in railroad switching and natural gas distribution led him to become involved in the then-new field of electrical power distribution. Electric lighting of streets using arc lighting was already a growing business with many companies building systems powered by either locally generated direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC). At the same time, Thomas Edison was launching the first DC electric utility designed to light homes and businesses with his patented incandescent bulb.

In 1884, Westinghouse began developing his own DC domestic lighting system and hired physicist William Stanley to help work on it. In 1885, Westinghouse became aware of the concept of an electrical transformer introduced by Frenchman Lucien Gaulard and Englishman John Gibbs. Guido Pantaleoni, an Italian engineer in his employ, alerted Westinghouse to their already-patented transformer and a deployed system capable of transmitting electricity for many miles near London, Turin, and Rome. They had found that AC electricity could be "stepped up" in voltage by a transformer for transmission and then "stepped down" by another transformer for lower voltage consumer use.[17] This innovation made it possible for large, centralized power plants to generate electricity and supply it over long distances to both cities and places with more dispersed populations. This was a huge advantage over the low voltage DC systems being marketed by Edison’s electric utility, which limited generating stations to a transmission range of about a mile due to losses cause by the low voltages and high currents used. Westinghouse recognized AC's potential to achieve greater economies of scale as a way to create a truly competitive electrical system, instead of simply piecing together a barely competitive DC lighting system just different enough to get around Edison’s patents.[18]

In 1885 Westinghouse imported several Gaulard–Gibbs transformers and a Siemens AC generator, to begin experimenting with AC networks in Pittsburgh. Stanley, assisted by engineers Albert Schmid and Oliver B. Shallenberger, dramatically improved the Gaulard–Gibbs transformer design, creating the first practical and manufacturable transformer.[19] In 1886, with Westinghouse's backing, Stanley installed the first multiple-voltage AC power system in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. The demonstration lighting system was driven by a hydroelectric generator that produced 500 volts AC, which was then stepped down to 100 volts to light incandescent bulbs in homes and businesses. That same year, Westinghouse founded the "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company";[20] in 1889 he renamed it the "Westinghouse Electric Corporation".

War of the currents

[edit]The Westinghouse company installed thirty more AC-lighting systems within a year, and by the end of 1887 it had 68 alternating current power stations compared to 121 DC-based stations Edison had installed over seven years.[21] This competition with Edison led, in the late 1880s, to what became known as the "war of currents". Thomas Edison and his company joined and promoted a spreading public perception that the high voltages used in AC distribution were unsafe and deadly. Edison even suggested that a Westinghouse AC generator should be used in the State of New York's new electric chair.

Westinghouse also had to deal with another AC rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, which had constructed 22 power stations by the end of 1887[21] and by 1889 it had acquired another competitor, the Brush Electric Company. Thomson-Houston was expanding its business while trying to avoid patent conflicts with Westinghouse, arranging deals such as agreements over lighting company territory, paying royalties to use the Stanley transformer patent, and allowing Westinghouse to use its Sawyer–Man incandescent bulb patent.

In 1890, the Edison company, in collusion with Thomson-Houston, arranged for the first electric chair to be powered with a Westinghouse AC generator. Westinghouse tried to block this move by hiring the best lawyer of the day to (unsuccessfully) defend William Kemmler, the first man scheduled to die in the chair.

The War of Currents ended in 1892 when financier J. P. Morgan forced Edison General Electric to switch to AC power and then pushed Edison out of the company he had founded.[22] Edison General Electric company was merged with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric, a conglomerate controlled by the board of Thomson-Houston.[23]

Development and competition

[edit]During this period, Westinghouse continued to pour money and engineering resources into the goal of building a completely integrated AC system — obtaining the Sawyer–Man lamp by buying Consolidated Electric Light, and developing components such as an induction meter,[24] and obtaining the rights to inventor Nikola Tesla's brushless AC induction motor along with patents for a new type of electric power distribution, polyphase alternating current.[25][26] The acquisition of a feasible AC motor gave Westinghouse a key patented element for his system, but the financial strain of buying up patents and hiring the engineers needed to build it meant that the development of Tesla's motor had to be put on hold for a while.[27]

In 1891, Westinghouse's company was in trouble. The near collapse of Barings Bank in London triggered the financial panic of 1890, causing investors to call in their loans.[28] The sudden cash shortage forced the company to refinance its debts. The new lead lenders demanded that Westinghouse cut back on what looked to them like his excessive spending on the acquisition of other companies, research, and patents.[28][29]

Also in 1891, Westinghouse built a hydroelectric AC power plant, the Ames Hydroelectric Generating Plant near Ophir, Colorado which supplied AC power to the Gold King Mine 3.5 miles away. This was the first successful demonstration of long-distance transmission of industrial-grade alternating current power and utilized two 100 hp Westinghouse alternators, one working as a generator producing 3,000-volt, 133-Hertz, single-phase AC, and the other used as an AC motor.[30]

In May 1892, Westinghouse Electric won the bid to power and illuminate the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago with alternating current, substantially underbidding General Electric to get the contract.[31][32][33] To meet the contract's demands, he had to quickly develop a new type of incandescent lightbulb based on the Sawyer–Man patent he had obtained, ensuring it did not infringe on the Edison patent design.

By the beginning of 1893, Westinghouse engineer Benjamin Lamme had made great progress in developing an efficient version of Tesla's induction motor. In that work he was aided by his sister and fellow Westinghouse engineer Bertha Lamme Feicht. Westinghouse Electric started branding their complete polyphase AC system as the "Tesla Polyphase System", announcing Tesla's patents gave them patent priority over other AC systems and stating their intention to sue any patent infringers.[34]

This World's Fair devoted a building to electrical exhibits. It was a key event in the history of AC power, as Westinghouse demonstrated the safety, reliability, and efficiency of a fully integrated alternating current system to the American public.[35]

Westinghouse's demonstration of their ability to build a complete AC system at the Columbian Exposition was instrumental in the company getting the contract for building a two-phase AC generating system, the Adams Power Plant, at Niagara Falls, NY, in 1895. The company was subcontracted to build ten 5,000 horsepower (3,700 kW) 25 Hz AC generators at this plant.[36] Westinghouse's Niagara Power Station No. 1, as it was then called, remained in operation in the Niagara transformer house until the plant closed in 1961.[37]

At the same time, a contract to build the three-phase AC distribution system the project needed was awarded to General Electric.[38] The early to mid-1890s saw General Electric, backed by financier J. P. Morgan, engaged in costly takeover attempts and patent battles with Westinghouse Electric. The competition was so costly that in 1896 a patent-sharing agreement was signed between the two companies. The agreement stayed in effect until 1911.[39]

Following the success of the first Niagara Falls plant, the Rankine Generating Station, also known as The Canadian Niagara Power Generating Station, the Canadians contracted with Westinghouse for eleven 25 Hertz generators of the same Tesla-inspired design, rated for a total generating capacity of 100 MW. That facility opened in 1905 in Niagara Falls, Ontario.

Other Westinghouse projects: steam engines, maritime propulsion, and shock absorbers

[edit]Despite continuing success in his other businesses, Westinghouse's main interest shifted to electric power. At the outset, the available generating sources were hydro turbines where falling water was available, and reciprocating steam engines where it was not. Westinghouse felt that existing reciprocating steam engines were clumsy and inefficient, and he wanted to develop rotating engines that would be more elegant. His first patent had been a rotary steam engine, but it proved impractical at the time.

In 1884, the British engineer Charles Algernon Parsons began experimenting with steam turbines, starting with a 10-horsepower (7.5 kW) turbine. In 1895, Westinghouse bought rights to the Parsons turbine, and his engineers improved its technology and increased its scale. In 1898, Westinghouse demonstrated a 300-kilowatt generating unit, replacing reciprocating engines in his air-brake factory. The next year, he installed a 1.5-MW 1200 rpm unit for the Hartford Electric Light Company.

Westinghouse also developed steam turbines for maritime propulsion. The basic problem was that large turbines ran most efficiently at around 3000 rpm, while an efficient propeller operated only at about 100 rpm. This required reduction gearing, but designing reduction gearing that could operate at both high rpm and at high power was difficult since any slight misalignment would shake the powertrain to pieces. Westinghouse and his engineers invented an automatic self-alignment system that finally made turbine power practical for large vessels.[40]

In 1889, Westinghouse purchased several mining claims in the Patagonia Mountains of southeastern Arizona and formed the Duquesne Mining & Reduction Company. He hoped to invent a better way to mine and extract copper from "lean" ores that were not particularly rich in the metal. Success is this venture would have helped him compete in the electrical businesses that used much copper.[41] He was unsuccessful in this project: no new copper reduction process was found and the mine was not profitable. He had founded the town of Duquesne to use as his company headquarters; it is now a ghost town. Duquesne grew to over 1,000 residents and the mine reached its peak production in the mid-1910s.[42][43]

Westinghouse also began to work on heat pumps that could provide heating and cooling. When Westinghouse claimed he was after a perpetual motion machine, the British physicist William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), one of his many correspondents, told him that such a machine would violate the laws of thermodynamics. Westinghouse replied that might be the case, but it made no difference. If he couldn't build a perpetual motion machine, he would still have a heat pump system that he could patent and sell.

After the broader introduction of the automobile, Westinghouse invented a compressed air shock absorber for their suspension systems.[44] The shock absorber was among the last of the 362 patents he received, and it was awarded posthumously, two years after his death.

Labor relations

[edit]Westinghouse was the first industrial employer in the United States to give workers a five-and-a half day work week, starting in June 1881. Saturdays were made half holidays to promote community involvement and personal development.[45][46] Westinghouse had observed the practice while visiting England.

The planned community of Wilmerding, Pennsylvania was home to many Westinghouse employees, and it was also the headquarters of several companies, particularly Westinghouse Air Brake. Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing was located a mile further down the Turtle Creek valley east of Pittsburgh. The worker houses were outfitted with running water, electricity, gas, and often space for small gardens. Homeownership was facilitated through periodic salary deductions. There was a pension and an insurance system. Factories were well-lit, ventilated, and were outfitted with medical facilities and personnel for treating injuries. All these accommodations, at Westinghouse's expense, were considered highly innovative at the time, especially in contrast to the conditions endured by workers in the nearby steel mills.[45][47]

Westinghouse was broadly admired by his workers. Privately, they referred to him as "the Old Man".[48][49] An indication of his progressive attitude was that when Westinghouse engineers invented things, they were allowed to keep their names on the patents, though assigning rights to use them to the company. Westinghouse viewed this as part of the dignity of man and part of his intellectual property.[50] Westinghouse, unlike Edison, did not put his name on all company patents as co-inventor.[51]

Westinghouse was not in favor of labor unionization. He did not reject workers who belonged to a union,[46] but he did not like collective bargaining arrangements where his workers might strike for issues not related to conditions at his own factories.[52] There was only one strike at any Westinghouse company while he was in charge. It was a 1903 action at Westinghouse Machine Company, which was rushing to illuminate the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair.[53] Westinghouse responded by immediately hiring replacements for those employees who walked out.[54] Despite that action, American labor and union organizer Samuel Gompers is reputed to have said "If all business leaders and moguls treated their employees as well as George Westinghouse, there’d be no need for any labor unions".[55] [56]

A series of short movies showing conditions in and around Westinghouse factories was made in 1904 and exhibited at the St. Louis World's Fair.[57]

Personal life, later life, and death

[edit]

In 1867, Westinghouse met Marguerite Erskine Walker on a train, and they married in August of that year. They were married for 47 years,[59] and had one son, George Westinghouse III, who in turn had six children.[60]

From 1871, George and Marguerite Westinghouse maintained a large home in Pittsburgh called Solitude, building up from an existing house on land purchased by George in 1871. They were part of a social class of very rich local industrialists and money managers including neighbors and associates Henry Clay Frick, Henry J. Heinz, William Thaw, Andrew Mellon, and Richard Beatty Mellon, and the brothers Andrew Carnegie and Thomas Carnegie.[61] Their guests included Nicola Tesla, Lord Kelvin, and congressman (and future president) William McKinley.

By 1893, they had constructed Erskine Park in Lenox, Massachusetts, which they used as a summer home, in part as a respite from the gritty industrial environment of Pittsburgh. It was named for the family of Marguerite's grandparents.[62]

In 1898, the Westinghouses leased and then in 1901 purchased the Blaine House mansion in Washington D.C. Marguerite Westinghouse was reputed to host frequent and lavish entertainments there.[63] In 1918, his former Pittsburgh home, Solitude, was razed and the land given to the City of Pittsburgh to establish Westinghouse Park. The house in Erskine Park was sold by the family in 1917 and subsequently demolished.

In 1894, the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization of Union Civil War veterans, held a week-long convention in Pittsburgh. George Westinghouse, being a veteran himself, hosted an evening of dinner and entertainment for more than 5,000 attendees at the newly constructed, but not yet active main buildings of the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company in East Pittsburgh. He took on the expenses of the necessary building preparations and all the expenses of transporting people to and from the site by rail.[64]

Pride in his achievements with the airbrake is reflected in the comment published in 1904: "If some day they say of me that with the airbrake I contributed something to civilization, something to the safety of human life, it will be sufficient."[65]

George Westinghouse remained a captain of American industry until 1907 when the financial panic of 1907 led to his resignation from control of the Westinghouse Electric company. By 1911, he was no longer active in business, and his health was in decline. [66] Westinghouse died on March 12, 1914, in New York City at age 67. He was initially interred in Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, NY then removed on December 14, 1915. As a Civil War veteran, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, along with his wife Marguerite, who survived him by three months. She had also been initially interred in Woodlawn but removed and reinterred at the same time as George.[67]

Honors and awards

[edit]George Westinghouse was deeply appreciated by his colleagues and employees. For example, Nicola Tesla, with whom he developed the AC polyphase system of electric power distribution spoke of him in 1938 as follows: "George Westinghouse was, in my opinion, the only man on this globe who could take my alternating-current system under the circumstances then existing and win the battle against prejudice and money power. He was a pioneer of imposing stature, one of the world's true noblemen, of whom America may well be proud and to whom humanity owes an immense debt of gratitude."[68]

List of Honors and Awards adapted from Ref.[69]

- In 1874, he was awarded the Scott Legacy Medal by the Franklin Institute.

- In 1884, he was awarded the Order of Leopold by Leopold II, King of the Belgians.

- In 1884 and 1889, he received the Order of the Royal Crown of Italy from Umberto I.

- In 1895, he was made a member of France's Legion of Honor.

- In 1905, the American Engineering Societies honored him with the John Fritz Medal.

- In 1906, the Berlin Royal Technical University awarded him an honorary doctorate of engineering.

- In 1910, he was elected president of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- In 1911, he was awarded the AIEE Edison Medal.

- In 1913, he became the first American to receive the Grashoff Medal from Germany.

- In 1915, Westinghouse High School, located in Pittsburgh, a mile from his former mansion, was named in his honor.

- In 1918, Solitude, his Pittsburgh home, was purchased by the Engineers Society of Western Pennsylvania and given to the city of Pittsburgh to establish Westinghouse Park. (The mansion was razed the following summer.)

- In 1930, the George Westinghouse Memorial, funded by 50,000 of his employees, was placed in Schenley Park in Pittsburgh.

- In 1932, the George Westinghouse Memorial Bridge was opened in 1932 to carry US Route 30 over the Turtle Creek Valley where his many companies had flourished. Its plaque reads:

|

- In 1936, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers organized a commemorative forum: Presenting the Career and Achievements of George Westinghouse on the 90th Anniversary of his Birth.

- Since 1953, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers has awarded a George Westinghouse Medal in the power field of mechanical engineering. Since 1972 there has been a gold medal and also a silver medal (for younger engineers).[70]

- In 1986, the George Westinghouse Jr. Birthplace and Boyhood Home in Central Bridge, New York, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[71]

- In 1989, Westinghouse was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

- December 1, 2018 was declared Westinghouse Park Centennial Day by Pittsburgh Mayor, William Peduto

- In 2019, The Westinghouse Park 2nd Century Coalition was organized.

- In 2021, Westinghouse's 175th birthday (his "dodransbicentennial") was celebrated, Westinghouse Park was certified as an arboretum and also determined eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

- In 2023, the Westinghouse Legacy 501.c3 organization[72] a 501(c)(3) non-profit, was established to promote the man and his accomplishments. It is building an online archive of information about George Westinghouse and advocating for on-going projects in the Pittsburgh park that bears his name, including the implementation of the city's master development plan for the park and development of long-term program of archeological research.

Timeline

[edit](Adapted from Library of Congress)[73]

- 1846: George Westinghouse born.

- 1865: George Westinghouse obtains first patent for rotary steam engine.

- 1867: Marries Marguerite Erskine Walker.

- 1869: George Westinghouse receives patent for the air brake. Westinghouse Air Brake Company organized with George Westinghouse as president.

- 1872: Automatic air brake invented.

- 1878: First foreign air brake company started at Sevran, France.

- 1881: Westinghouse Machine Company formed. The Westinghouse Brake Company, Ltd., in London, England, founded.

- 1881: The air brake company institutes Saturday half-holiday.

- 1882: Union Switch and Signal Company organized.

- 1884: The Westinghouse Brake Company, Ltd., in Hanover, Germany, founded.

- 1886: Westinghouse Electric Company, later known as the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, formed.

- 1889: Ground broken for air brake factory at Wilmerding, PA.

- 1890: Westinghouse began manufacture of electric railway motors.

- 1893: Westinghouse Electric company lights Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

- 1895: Main works for Electric and Manufacturing Company built in East Pittsburgh.

- 1896: Generators built by Westinghouse turn the waters of Niagara Falls into electric power.

- 1898: Westinghouse Company, Ltd., in St Petersburg, Russia organized.

- 1899: The British Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company, Ltd., formed in London, England, with another plant in Manchester.

- 1901: Societe Anonyme Westinghouse organized with offices in Paris, and works in Le Havre and Freinville. The Westinghouse Electricitats-Actiengesellschaft organized in Berlin.

- 1903: Canadian Westinghouse Company, Ltd., founded. Relief Department (disability benefits, medical and surgical services) founded.

- 1904: The American Mutoscope & Biograph Co. films motion pictures of the Westinghouse Works.[57] Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis—Westinghouse Co. displays several large exhibits, holds screenings of the AM&B films, and supplies power generators and equipment for the exposition's service plant.

- 1905: Electrification of the Manhattan Elevated Railways and the New York subway system.

- 1907: George Westinghouse loses control of his companies.

- 1911: George Westinghouse severs all ties with his companies.

- 1914: George Westinghouse dies.

- 1918: George Westinghouse receives his final patent, 4 years after his death.

Companies and geographical distribution

[edit]During his lifetime, the companies of George Westinghouse were widely distributed in the Pittsburgh region. Their locations, and the locations of several other major industrial enterprises, are numbered in the image and are itemized here:[74]

- Westinghouse Air Brake: 25th Street and Liberty Avenue

- Westinghouse Air Brake: Allegheny City

- Westinghouse Air Brake: Wilmerding

- Union Switch & Signal and Westinghouse Electric: Garrison Alley

- Union Switch and Signal: Swissvale

- First Westinghouse home and gas wells: "Solitude"

- Haymaker gas wells: Murrysville

- Other gas wells: Murrysville

- Fuel gas line: Murrysville to Pittsburgh

- Edgar Thomson Works of Carnegie Steel: Braddock

- Carnegie Steel Company: Homestead

- Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing: East Pittsburgh

- Westinghouse Machine Company

- Westinghouse Foundries: Trafford

References

[edit]Patents

[edit]Below is a sampling of U.S. patents for inventions by George Westinghouse. Many of the same inventions were also patented in foreign countries, including Austria, Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Spain, and Switzerland. Many other patents were filed in the names of his companies or various of his engineers.

- U.S. patent 34,605, 1862, grain and seed winnowers; patent awarded to father George Westinghouse Sr.

- U.S. patent 50759A, 1865, improvement in rotary steam-engines; 1st patent awarded to George Westinghouse Jr.

- U.S. patent 61967A, 1867, improved railroad switch and car replacer; device to help put derailed train car back on track

- U.S. patent 76365A, 1868, improved railway frog; device for switching trains between tracks

- U.S. patent 88929A, 1869, improvement in steam-power-brake devices; the air brake

- U.S. patent 106,899, 1870, improvements in steam engine and pump

- U.S. patent 109,695, 1870, improvement in atmospheric car-brake pipes

- U.S. patent 144,006, 1873, improvement in steam and air brakes

- U.S. patent 136,631, 1873, improvement in steam-power-brake couplings

- U.S. patent 149,901, 1874, improvement in valves for fluid brake-pipes

- U.S. patent 159,533, 1875, pneumatic pump

- U.S. patent 223,201, 1879, improvement in auxiliary telephon exchanges

- U.S. patent 223,202, 1879, automatic telephone switch for connecting local lines by means of main line

- U.S. patent 218,149, 1879, improvement in fluid-pressure brake apparatus

- U.S. patent 246,053, 1881, interlocking switch and signal apparatus

- U.S. patent 280,269, 1883, fluid-pressure regulator

- U.S. patent 301,191, 1884, system for conveying and utilizing gas under pressure

- U.S. patent 306,566, 1884, means for detecting leaks in gas mains

- U.S. patent 314,089, 1885, system for the protection of railroad-tracks and gas-pipe lines

- U.S. patent 330,179, 1885, means for detecting and carrying off leakage from gas mains

- U.S. patent 342,552, 1886, system of electrical distribution

- U.S. patent 342,553, 1886, induction coil

- U.S. patent 357,295, 1887, commutator for dynamo electric machines

- U.S. patent 366,362, 1887, electrical converter; a type of transformer

- U.S. patent 373,035, 1887, system of electrical distribution

- U.S. patent 357,295, 1888, electric meter (with Philip Lange)

- U.S. patent 399,639, 1889, system of electrical distribution

- U.S. patent 400,420, 1889, fluid-meter

- U.S. patent 425,059, 1890, fluid-pressure automatic brake mechanism

- U.S. patent 427,489, 1890, alternating current electric meter

- U.S. patent 437,740, 1890, fluid-pressure automatic brake

- U.S. patent 676,108, 1890, electric railway system

- U.S. patent 446,159, 1891, switch and signal apparatus

- U.S. patent 454,129, 1891, pipe-coupling

- U.S. patent 499,336, 1893, draw-gear apparatus for cars

- U.S. patent 497,394, 1893, conduit electric railway

- U.S. patent 543,280, 1895, incandescent electric lamp

- U.S. patent 550,465, 1895, electric railway

- U.S. patent 579,506, 1897, current-collecting device for railway-vehicles

- U.S. patent 579,525, 1897, system of circuits and apparatus for electric railways

- U.S. patent 595,007, 1897, elevator

- U.S. patent 595,008, 1897, electric railway

- U.S. patent 609,484, 1898, fluid pressure automatic brake

- U.S. patent 645,612, 1899, method of distributing energy

- U.S. patent 672,114, 1900, draft appliance for railway cars

- U.S. patent 672,117, 1900, draw-gear and buffing apparatus

- U.S. patent 687,468, 1900, draw-gear and buffing apparatus

- U.S. patent 727,039, 1900, automatic fluid pressure brake apparatus

- U.S. patent 773,832, 1903, controlling system for electric motors

- U.S. patent 922,827, 1908, gearing

- U.S. patent 972,421, 1908, turbine

- U.S. patent 1,031,759, 1912, vehicle supporting device; a shock absorber

- U.S. patent 1,185,608, 1916, automobile air spring

- U.S. patent 1,284,006, 1918, automatic train control (filed by his executors)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Becerra-Fernandez, Irma; Rajiv Sabherwal (2014). Knowledge Management: Systems and Processes. Taylor & Francis. p. 241. ISBN 9781317503026 – via Google Books.

- ^ "George Westinghouse". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ "Westinghouse__George.html". PSU.edu. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 11.

- ^ Variants of the name used by descendants include Wistinhausen, Wistenhausen and Wistenhaus.

- ^ Register of Commissioned Officers of the United States Navy. 1865. p. 209.

- ^ Huber, William R. (2022). George Westinghouse, Powering the World. McFarland & Co. p. 17.

- ^ George Westinghouse article at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ He later patented the device. It was issued as U.S. patent 76,365 in April 1868, when he was 22. It was reissued as U.S. patent RE3584 in August 1869.

- ^ "The Life of a Brakeman – The Neversink Valley Museum of History & Innovation". Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 29.

- ^ Witzel, Morgen, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of the History of American Management (1st ed.). Continuum – via Credo Reference.

- ^ Geisst, Charles R., ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of American Business History (1st ed.). Facts on File – via Credo Reference.

- ^ a b Pittsburgh and Allegheny Illustrated Review. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: J. M. Elstner & Co. 1889. p. 32.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 69.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 73.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 78.

- ^ Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age by W. Bernard Carlson. Princeton University Press. 2013. p. 89.

- ^ "William Stanley – Engineering Hall of Fame". Edison Tech Center. 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Steam Hammer, Westinghouse Works, 1904". World Digital Library. May 1904. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ a b Bradley, Robert L. Jr. (2011). Edison to Enron: Energy Markets and Political Strategies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 50. ISBN 978-1118192511. Retrieved 7 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Skrabec, Quentin (2007). George Westinghouse: Gentle Genius. New York: Algora Pub. p. 97. ISBN 978-0875865089. OCLC 123307869.

- ^ Bradley, Robert L., Jr. (2011). Edison to Enron: Energy Markets and Political Strategies. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-47091-736-7, pp. 28–29

- ^ Seifer, Marc (24 October 2011). Marc Seifer, Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla, p. 1713. Citadel. ISBN 9780806535562.

- ^ Klooster, John W. (2009). John W. Klooster, Icons of Invention: The Makers of the Modern World from Gutenberg to Gates, p. 305. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780313347436.

- ^ Jonnes, Jill (19 August 2003). Jill Jonnes, Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World, Edison Declares War. Random House Publishing. ISBN 9781588360007.

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 127.

- ^ a b Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age by W. Bernard Carlson. Princeton University Press. 2013. p. 130.

- ^ Jill Jonnes (2004). Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World, Random House, p. 29 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 147.

- ^ Moran 2002, p. 97.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 139.

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 135-137.

- ^ Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, Princeton University Press, p. 167 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Chaim R. Rosenberg (2009). America at the Fair: Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Arcadia Publishing, [ISBN missing] [page needed]

- ^ Harnessing Niagara Edison Tech Center

- ^ Christian, Ralph J.; James Gardner (9 September 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Adams Power Plant Transformer House" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying photos, exterior and interior, from 1978. (2.61 MB)

- ^ Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, Princeton University Press, pp. 167–173

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 190.

- ^ Prout 1921, p. 190.

- ^ Prout, Henry (1921). A Life of George Westinghouse. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-4400-5846-2.

- ^ John and Bette Bosma (April 2006). "Southwest Arizona Ghost Towns Harshaw, Mowry, Washington Camp, Duquesne, Lochiel" (PDF). Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Sherman, James E. & Barbara H. (1969). Ghost Towns of Arizona. University of Oklahoma. ISBN 0806108436.

- ^ Prout 1921, p. 252.

- ^ a b Huber 2022, p. 44.

- ^ a b Prout 1921, p. 294.

- ^ Reis 2008.

- ^ Leupp 1918, p. 247.

- ^ Prout 1921, p. 287.

- ^ Shigehiro Nishimura (August 2012). "The rise of the patent department: A case study of Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company" (PDF). Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Reis, Ed. “A Man for His People.” Mechanical Engineering Magazine October 2008: 32-35

- ^ Leupp 1918, p. 254.

- ^ "Strike May Cripple Fair". New York Times. 12 September 1903.

- ^ Terrell, Ellen (July 2021). "American Dynamo: The Life of George Westinghouse". Library of Congress.

- ^ Wohleber, Curt (1997). ""St. George" Westinghouse". Invention and Technology Magazine.

- ^ Reis 2022Small variations of this quote can be found in various sources.

- ^ a b Library of Congress Essay. "Inside an American Factory: Films of the Westinghouse Works, 1904". Library of Congress.

- ^ Leupp, Francis Ellington (1918). George Westinghouse, His Life and Achievements. Boston, Little Brown and Co.

- ^ Prout 1921, p. 8.

- ^ Westinghouse clan gathers here, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 10, 2008

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 63.

- ^ "Erskine Park". Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ "Blaine Mansion". Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 163.

- ^ Warren, Arthur (6 March 1904). "A Hundred-Thousand-Horse-Power Man". The New York Times.

- ^ Skrabec 2007.

- ^ "Burial Detail: George Westinghouse". ANC Explorer.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 155.

- ^ Reis, Ed (2008). "A Man for His People". Mechanical Engineering. 130 (10). American Society of Mechanical Engineers: 32–35. doi:10.1115/1.2008-OCT-3. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "George Westinghouse Medal". ASME. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 13 March 2009.

- ^ The Westinghouse Legacy 501.c3 organization

- ^ "George Westinghouse Timeline". Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Huber 2022, p. 6.

Bibliography

[edit]- Huber, William R. (2022). George Westinghouse, Powering the World. North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-1-4766-8692-9

- Fraser, J. F. (1903). America at work. London: Cassell. Page 223+.

- Leupp, Francis E. (1918). George Westinghouse; His Life and Achievements Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Prout, Henry G. (1921). A Life of George Westinghouse.

- Skrabec, Quentin (2007). George Westinghouse: Gentle Genius, New York: Algora Publishing ISBN 978-0875865089

- Hubert, P. G. (1894). Men of achievement. Inventors. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Page 296+.

- Jonnes, Jill (2003). Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-75884-3

- Klein, Maury (2009). The Power Makers: Steam, Electricity, and the Men Who Invented Modern America. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1596916777

- Moran, Richard (2002). Executioner's current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the invention of the electric chair. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-72446-6.

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Transactions of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. The electrification of Railways, G. Westinghouse. Page 945+.

- New York Air Brake Company (1893). Instruction book. 1893.

- Westinghouse Air Brake Company. (1882). Westinghouse automatic brake. (ed., Patents on p. 76.)

External links

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Westinghouse Corporation

- Booknotes interview with Jill Jonnes on Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse and the Race to Electrify the World, October 26, 2003.

- ANC Explorer – Westinghouse's grave at Arlington National Cemetery

- Westinghouse Park 2nd Century Coalition

- The Westinghouse Legacy 501.c3 organization

- American company founders

- American electrical engineers

- American industrialists

- American inventors

- American railroad mechanical engineers

- Westinghouse Electric Company

- 1846 births

- 1914 deaths

- Presidents of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers

- Fellows of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers

- Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

- IEEE Edison Medal recipients

- John Fritz Medal recipients

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Union College (New York) alumni

- Businesspeople from Schenectady, New York

- People from Schoharie, New York

- People from Lenox, Massachusetts

- Engineers from New York (state)

- Military personnel from Schenectady, New York

- American people of German descent

- 19th-century American businesspeople

- Union army non-commissioned officers

- Union Navy sailors