Historic Centre of Lima

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

View of the Cathedral and the main square | |

| Location | Lima, Peru |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 500bis |

| Inscription | 1988 (12th Session) |

| Extensions | 1991, 2023 |

| Area | 259.36 ha (640.9 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 766.7 ha (1,895 acres) |

| Coordinates | 12°3′5″S 77°2′35″W / 12.05139°S 77.04306°W |

The Historic Centre of Lima (Spanish: Centro histórico de Lima) is the historic city centre of the city of Lima, the capital of Peru. Located in the city's districts of Lima and Rímac, both in the Rímac Valley, it consists of two areas: the first is the Monumental Zone established by the Peruvian government in 1972,[1] and the second one—contained within the first one—is the World Heritage Site established by UNESCO in 1988,[2] whose buildings are marked with the organisation's black-and-white shield.[a]

Founded on January 18, 1535, by Conquistador Francisco Pizarro, the city served as the political, administrative, religious and economic capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru, as well as the most important city of Spanish South America.[4] The evangelisation process at the end of the 16th century allowed the arrival of several religious orders and the construction of churches and convents. The University of San Marcos, the so-called "Dean University of the Americas", was founded on May 12, 1551, and began its functions on January 2, 1553 in the Convent of Santo Domingo.[5]

Originally contained by the now-demolished city walls that surrounded it, the Cercado de Lima features numerous architectural monuments that have survived the serious damage caused by a number of different earthquakes over the centuries, such as the Convent of San Francisco, the largest of its kind in this part of the world.[2][6] Many of the buildings are joint creations of artisans, local artists, architects and master builders from the Old Continent.[2] It is among the most important tourist destinations in Peru.

History

[edit]

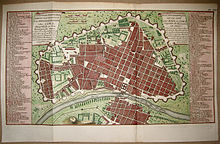

The city of Lima, the capital of Peru, was founded by Francisco Pizarro on January 18, 1535, and given the name City of the Kings.[7][8] Nevertheless, with time its original name persisted, which may come from one of two sources: Either the Aymara language lima-limaq (meaning "yellow flower"), or the Spanish pronunciation of the Quechuan word rimaq (meaning "talker", and actually written and pronounced limaq in the nearby Quechua I languages). It is worth nothing that the same Quechuan word is also the source of the name given to the river that feeds the city, the Rímac River (pronounced as in the politically dominant Quechua II languages, with an "r" instead of an "l"). Early maps of Peru show the two names displayed jointly.

Under the Viceroyalty of Peru, the authority of the viceroy as a representative of the Spanish monarchy was particularly important, since its appointment supposed an important ascent and the successful culmination of a race in the colonial administration. The entrances to Lima of the new viceroys were specially lavish. For the occasion, the streets were paved with silver bars from the gates of the city to the Palace of the Viceroy.[citation needed]

In 1988, UNESCO declared the historic centre of Lima a World Heritage Site for its originality and high concentration of historic monuments constructed during the viceregal era.[2][7] In 2023, it was expanded with two exclaves to include the Quinta and Molino de Presa and the Ancient Reduction of Santiago Apostle of Cercado.[2]

Since the 2010s, Spanish–Peruvian real estate company Arte Express has been granted ownership of a number of buildings in the area, having been since restored.[9][10] In 2021, as part of renovation works made in preparation for the bicentennial celebrations of that year, the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima installed 206 different QR codes across different landmarks of the centre that, when scanned, open a video that details the selected building's history.[11]

On January 18, 2024, the city's 489th anniversary, president Dina Boluarte announced a "special regime" that targets the area in order to allow restoration and repair works to take place.[12] On January 17, 2025, the municipal authorities relaunched Lima, Ciudad de los Reyes, a patronage aimed at the promotion of the restoration of the city's cultural heritage sites.[13]

List of sites

[edit]The World Heritage Site, divided into three zones,[2] features a number of landmarks.

Historic Centre of Lima

[edit]The main zone is that of the Historic Centre of Lima (266.17 ha; buffer zone: 806.71 ha),[2] which features the following:

List of Landmarks included within the UNESCO World Heritage Site

| |||

| Name | Location | Notes | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balconies of Lima | Various | Over 1,600[citation needed] were built in total in both the viceregal and republican eras of the city. They have been crucial in UNESCO's declaration of the historic centre as a World Heritage Site.[2] |  |

| Acho Bullring | Jr. Marañón 569 Jr. Hualgayoc 332 |

It is the oldest bullring in the Americas[7] and the second-oldest in the world after La Maestranza, in Spain. It opened on January 30, 1766, and has a seating capacity of 13,700 people. A watch tower overlooks the bullring since 1858.[14] |  |

| Aero Club del Perú | Jr. Unión 718, 722, 726, 732 | The building was owned by Juan Bautista Palacios, Knight of the Order of Santiago, and rented by the Aero Club del Perú since 1935, who used it as its headquarters. It eventually ceased to be used by the club and was later turned into a commercial gallery. |  |

| Alameda Chabuca Granda | The promenade is built in the site of the former Polvos Azules marketplace, itself occupying the former site of the Venetian Palace. Named after singer-songwriter Chabuca Granda, it features an auditorium and a large sculpture. | ||

| Alameda de los Descalzos | One of the best-known places in the district, around it stand a number of churches and the former residence of Micaela Villegas. |  | |

| Archbishop's Palace | Jr. Junín & Carabaya | The home of the Archbishop of Lima, it was turned into an episcopal seat in 1541 by Pope Paul III and rebuilt in 1924 by architects Claude Sahut and Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski as part of the city works commissioned by Augusto B. Leguía in preparation of the centennial celebrations of the Battle of Ayacucho.[15] |  |

| Banco Internacional del Perú (1923) | Jr. Sta. Rosa | The building dates back to 1923 and formerly served as the headquarters of the bank of the same name. It is one of several buildings owned by Arte Express.[9] |  |

| Banco Internacional del Perú (1942) | Plazoleta de la Merced | The property was purchased in 1942, where the bank constructed its building, designed by architects Rafael Marquina y Bueno and José Álvarez Calderón, to house its agency. In 2011, its structure was remodelled to house two shopping malls: Oechsle and Plaza Vea.[16] |  |

| Banco Italiano | Jr. Lampa & Ucayali | The building, a property of the bank of the same name, was inaugurated on April 21, 1929, coinciding with both the 40th anniversary of the bank's creation and the founding of Rome.[17] It was designed by architect Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski.[18] |  |

| Banco del Perú y Londres | Jr. Azángaro & Huallaga | Named after the bank of the same name, it was designed by architect Julio Ernesto Lattini in 1905.[19] The work was commissioned by the bank's director, José Payán.[20] It was later acquired by the Banco Popular del Perú.[21] After the bank declared bankruptcy in the 1990s, it was acquired by Congress and is currently known as the Edificio Luis Alberto Sánchez, named after the APRA politician. |  |

| Banco Wiese | Jr. Carabaya & Cuzco | Originally the seat of a bank of the same name, it was designed by Enrique Seoane Ros and inaugurated on December 6, 1963, in a ceremony attended by president Fernando Belaúnde. Around 2002, the bank building was remodelled to accommodate a Metro supermarket.[16] | — |

| Basilica and Convent of Saint Augustine | Jr. Camaná & Ica | Located in front of a public square of the same name, it has been run by the Augustinian friars since its foundation, and belongs to the Province of Our Lady of Grace of Peru. |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Saint Dominic | Jr. Camaná & Conde de Superunda | The 16th century complex, originally named after Our Lady of the Rosary, is named after Saint Dominic. It is also the site where the Royal University of Lima was founded in 1551, and was elevated to basilica in 1930. A square named after María Escobar is located across the street.[22] |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Saint Francis | Jr. Áncash & Lampa | The 17th century complex is named after Francis of Assisi. It is the site of the Museum of Religious Art and of the Zurbarán Room, as well as an underground network of galleries and catacombs that served as a cemetery during the Viceregal era. |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Saint Peter | Jr. Azángaro & Ucayali | The 17th century complex, formerly named after Saint Paul and featuring a college of the same name, is named after Saint Peter since 1767. It is the burial site of Viceroy Ambrosio O'Higgins, as well as the site of the heart of the Viceroy Count of Lemos.[23] |  |

| Basilica and Convent of Our Lady of Mercy | Jr. Unión & Sta. Rosa | The 16th century complex is named after Our Lady of Mercy, who serves as the patroness of the Peruvian Armed Forces. Its Churrigueresque style dates back to the 18th century. The public square next to it was the location of one of José de San Martín's proclamations of the independence of Peru in 1821.[24] |  |

| Caja de Depósitos y Consignaciones | Jr. Huallaga 400 | Designed by Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski, the building was completed in 1917 and housed the private bank of the same name until its nationalisation in 1963.[25] It was subsequently donated by the Peruvian government to the National Superior Autonomous School of Fine Arts on September 27, 1996. |  |

| Casa de la A.A.A. | Jr. Ica 323 | The building houses a theatre company and cultural institution founded on June 13, 1938. |  |

| Casa Alarco | Jr. Callao 482 | The house is named after the family of the same name, and features two commemorative plaque at its entrance. They commemorate the lives of Antonio Alarco Espinosa, who died at the battle of Callao,[26] and Juana Alarco de Dammert, who was born there in 1842. |  |

| Casa Aliaga | Jr. Unión 225 | The building—the oldest in the city—dates back to May 1536, belonging to Conquistador Jerónimo de Aliaga and built on top of a pre-Columbian sanctuary. It was destroyed by the earthquake of 1746 and rebuilt by Juan José Aliaga y Sotomayor. In the 19th century a series of works were carried out.[27] |  |

| Casa Arenas Loayza | Jr. Junín 270 | Unlike many other similar residences from the mid-19th century, its plan does not develop around a central patio or in general around any axis. Its interior is decorated with plasterwork with a floral motif. The ground floor is mostly intended for longitudinal shops. |  |

| Casa Aspíllaga | Jr. Ucayali 391 | Named after politician Ántero Aspíllaga Barrera, who lived there. It was first registered in 1685, and its current design corresponds to a 19th-century neoclassical republican style. It was acquired by the state in 1953 and administered by the Foreign Ministry. It currently functions as the Inca Garcilaso Cultural Centre. |  |

| Casa Barbieri | Jr. Callao & Rufino Torrico | Originally the property of the Cabildo of Lima prior to the 1748 earthquake and then of the counts of Villar de Fuentes, it was purchased by Manuel Fernando Barbieri Sprinborn in the 1920s, who renovated it. A devout Catholic, he died at home, having been cared for by the nuns of the convent San José, in Barrios Altos. These nuns inherited the building in 1975 and later put it up for sale.[28] |  |

| Casa Barragán | Jr. Unión & Av. Emancipación | Named after Genaro Barragán Urrutia, who had it built, it was best known for housing the Palais Concert, an entertainment venue inspired by the Café de la Paix in Paris that featured a bar, coffee shop and cinema that attracted the city's intellectuals during the early 20th century. The bar closed in 1930, and the building was subsequently repurposed as a mall that included a nightclub, the Discoteca Cerebro, until it was ultimately purchased by Ripley S.A. in 2011, opening its department store a year later. |  |

| Casa Bodega y Quadra | Jr. Áncash 209, 213 & 217 | Located on the remains of a terrain that dates back to the Viceroyalty of Peru, it illustrates the daily life of people during the Spanish and Republican era of the city. It is named after the final family that owned it during the 17th century. |  |

| Casa Bolognesi | Jr. Cailloma 125 | Located at the birthplace of Francisco Bolognesi, it currently functions as a house museum dedicated to the War of the Pacific and the battle where he died in 1880. |  |

| Casa Candamo | Jr. Carabaya & Ucayali | The building dates back to the mid 19th century, and is named after Manuel Candamo, who lived there. Candamo was twice president of Peru in 1895 and from 1093 to 1904. |  |

| Casa de Correos y Telégrafos | Jr. Conde de Superunda 170 | Originally the city's post office since 1872, it now hosts two museums: one dedicated to philately, inaugurated in 1931, and another one dedicated to Peruvian cuisine, opened in 2011. |  |

| Casa Courret | Jr. Unión 459 | Designed by architect Enrique Ronderas, this building housed the studio of photographer Eugène Courret until 1906, when he was succeeded by Adolphe Dubreuil. The studio was one of the most prolific of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the photographs taken there formed the archive that served as a graphic encyclopedia for the history of the city.[29] |  |

| Casa de la Columna | Jr. Conde de Superunda | Originally a cloister that formed part of the nearby Convent of Saint Dominic, it currently serves as the residence of over 200 people that have inhabited the building for generations since the 19th century.[30] | — |

| Casa de la Cultura Criolla | Jr. Moquegua 376 | The 18th century building was the residence of songwriter Rosa Mercedes Ayarza for the final 29 years of her life. In 2022, a museum named after her was inaugurated in 2022, featuring a section dedicated to Ayarza and other sections detailing the history of the building, among other things.[31] |  |

| Casa de Divorciadas | Jr. Carabaya 641 | Built in the 18th century, it originally functioned as a residence for divorced women.[32] It is currently operated by de Charity of Lima.[33] |  |

| Casa Dubois | Jr. Unión 780 | Also known as the Casa de Piedra, it was designed by Jacob Wrey Mould and built using materials brought from New York City and Scotland.[34] During the centennial celebrations in 1921, due to the lack of space in the city, the Dubois family offered to house the visiting Pontificial delegation, who were guarded by the presidential guard during their stay.[35] It currently houses the Cinestar Excelsior, a movie theatre. |  |

| Casa de los duques de San Carlos | Jr. Junín 387 & Azángaro | The house is named after the noble family that owned it, and during the Peruvian War of Independence, it housed Simón Bolívar in 1823 upon his arrival to Lima to consolidate the country's independence. It was declared a National Monument in 1972 and is currently the residence of 30 families and the location of a restaurant.[36] |  |

| Casa Federico Elguera | Jr. Huallaga 458–466 | The 19th-century building originally served as a residence, later modified to house several families. Its best known inhabitant was politician Federico Elguera, who served as mayor of Lima from 1901 to 1908. A plaque in his honour is found next to the entrance, while the building has been repurposed as a commercial gallery.[37] |  |

| Casa Fernandini | Jr. Ica 400 | The building was designed by Claude Sahut in an eclectic style for the miner Eulogio Fernandini and his family. It is currently a museum where cultural activities take place regularly. |  |

| Casa de Goyeneche | Jr. Ucayali 358 | The 959.20 m2 two-storey building was built during the 18th century and is named after the family that formerly owned it. After passing through a series of different owners, it was ultimately acquired by the Banco de Crédito del Perú in 1971.[38] |  |

| Casa Grau | Jr. Huancavelica 170 & 172 | For 12 years, the building served as the residence of Peruvian War hero Miguel Grau. It currently functions as a house museum dedicated to his memory. |  |

| Casa Gutiérrez | Jr. Unión & Cuzco | The 16th century building is named after Pedro Gutiérrez, the tailor who owned it in 1537. In 1872, it was remodelled by José Jiménez (also being known as the Casa Jiménez), making most of the building look like it did when it was first built. It was renovated in 1940 by the Compañía de Seguros Atlas in honour of the city's 450th anniversary. Restoration works were carried out in the 1980s under the direction of architect José Correa Orbegoso. |  |

| Casa Gutiérrez de Coca | Jr. Carabaya 460 | Also known simply as the Casona Coca, the building dates back to 1780, being significantly modified up until the 19th century.[39] It is one of many buildings restored by Arte Express.[9] | — |

| Casa Harth | Jr. Azángaro & Junín | The building, which dates back to 1755,[9] was owned by Antonio de Querejazu y Mollinedo, who served as oidor and belonged to one of the richest families of the city. It was eventually acquired by Teodoro Harth and his company, founded in 1854, receiving its current name.[40] It was purchased by Arte Express in 2019.[40] |  |

| Casa L'eau Vive | Jr. Ucayali 370 | The building is the property of the Archdiocese of Lima and houses the L’Eau Vive del Perú restaurant since 1982, operated by a group of nuns from Peru, Vietnam, Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Kenya. Due to its religious nature, it is in charge of feeding locals in need.[41] |  |

| Casa de la Literatura Peruana | Jr. Áncash & Carabaya | Originally a train station named after the adjacent church, the building has since been converted into a cultural centre that was inaugurated on October 20, 2009. |  |

| Casa de Manuel Atanasio Fuentes | Jr. Sta. Rosa 360 | Named after Manuel Atanasio Fuentes, the writer and journalist who lived there, it housed the General Directorate of Public Instruction during the early 20th century. A plaque installed in 1935 is dedicated to his memory. |  |

| Casa Marcionelli | Jr. Carabaya 955 | Built by Swiss businessman Severino Marcionelli, it housed his offices, a consulate of Switzerland, and was eventually burned down in 2023, with only the first floor's façade remaining.[42][43] |  |

| Casa del Mariscal Ramón Castilla | Jr. Cuzco 210, 218 & 224 | The building, later known as the Casa de Castilla, was purchased by Ramón Castilla in 1840. It was declared a national monument in 1972, then owned by the Montori family. It was due to be demolished in 1976, until housing minister Gerónimo Cafferata Marazzi announced on November 17 that the run-down structure would not be demolished, but instead restored.[44] |  |

| Casa Mendoza | Jr. Junín 429 | The building was owned by Francisco Mendoza Ríos y Caballero in 1857, owned by his descendants until 1943, when it was sold to the Viuda de Piedra e hijos company.[45] |  |

| Casa de Moneda | Jr. Junín 781 | The building's houses the national mint of the country, whose origin dates back to 1565. |  |

| Casa del Oidor | Jr. Junín & Carabaya | The building was built on two of the four plots that made up one of the 117 blocks into which Lima was initially divided. Also damaged and rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake,[46] it is best known for the large balcony that runs through its façade.[47] |  |

| Casa O'Higgins | Jr. Unión 554 | Named after Bernardo O'Higgins, who lived and died there, it is currently operated by the Riva-Agüero Institute. |  |

| Casa de Osambela | Jr. Conde de Superunda 298 | Built on the former grounds of a novitiate of the Dominican Order that was destroyed during the 1746 earthquake, it is currently the headquarters of the Academia Peruana de la Lengua and the regional office of the Organization of Ibero-American States. |  |

| Casa de Pilatos | Jr. Áncash 390 | Built in the late 16th century, it was occupied by various families of the aristocracy of Lima for most of its history,[48][49] being purchased by the government during the 20th century. It currently functions as the de facto headquarters of the Constitutional Court. |  |

| Casa Pygmalión | Jr. Unión 471 | Designed by the Masperi Brothers, the building was commissioned by the Moreyra y Riglos family.[50][51] The building served as a clothing store during the early 20th century, importing clothes and fabric from Europe. |  |

| Casa Rehder | Jr. Unión 483 | The building bears the sign of the prominent department store that existed during the early 20th century. It was purchased in 1955 by Fred Noetzli and succeeded by the Casa Mercaderes S.A., of the same purpose. It changed hands again in 1962.[52] |  |

| Casa de Ricardo Palma | Jr. Ayacucho 358, 364 | The house, located in the third block of the street, is the birthplace of Peruvian writer Ricardo Palma (1833–1919) and his residence during the first five years of his life.[53] It features a bronze plaque dedicated to his memory, added to the building in 1920.[54] It currently functions as a clothing store.[55][56][57] |  |

| Casa Rímac | Jr. Junín 323[58] | Formerly the headquarters of the Compañía International de Seguros del Perú, it continues to bear the name of the company. The Spanish–Peruvian real estate company Arte Express acquired the building, establishing it as its headquarters.[9] |  |

| Casa Riva-Agüero | Jr. Camaná 459 | This house was constructed in the 18th century by the Riva Agüero family, whose last member, the intellectual José de la Riva-Agüero, donated it to the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. It currently serves as the headquarters of the university's Riva-Agüero Institute, where its archive and library are located. |  |

| Casa de San Martín de Porres | Jr. Callao 534 | The house is the birthplace of Martín de Porres, a member of the Dominican Order who was beatified in 1837 and canonised in 1962. It currently functions as a museum dedicated to his life, also serving as a soup kitchen and meeting place for people in need.[59] |  |

| Casa de ejercicios de Santa Rosa de Lima | Jr. Sta. Rosa 448 | The building serves as a spiritual retreat and a museum dedicated to its history, as well as that of Rose of Lima, after which it's named.[60] |  |

| Casa de la Torre | Jr. Ayacucho & Junín | The house is named after Manuel C. de la Torre,[61] who lived there and fought in the Morro de Arica during the War of the Pacific. A plaque installed in 2021 is dedicated to his memory. |  |

| Casa de las Trece Monedas | Jr. Áncash 536 | The building belonged to the López-Flores family, Counts of Puente Pelayo, owing its name to the thirteen coins featured in the family's coat of arms. It currently operates as the National Afro-Peruvian Museum. |  |

| Casa de las Trece Puertas | Jr Áncash & Lampa | Its name comes from the number of doors it has, a total of thirteen. It originally had nine doors when it was built during the 17th century, eventually growing due to the number of businesses housed in the building. Destroyed during the 1746 earthquake, the current building was built in the Rococo style[62] between 1864 and 1872, acquired by the Provincial Council of Lima in 1975 and ultimately restored from 2007 to 2009.[63] |  |

| Casa Welsch | Jr. Unión & Ica | The Art Nouveau-style building is named after the German retail company of the same name.[64] The company's history dates back to the 19th century, although its building was inaugurated on December 11, 1909. Its architects were Raymundo and Guido Masperi. In 1942, due to the anti-German sentiment caused by World War II, its Longines clock was replaced by an IBM one instead after the building was attacked. The store ultimately closed in 1991.[65] |  |

| Catacombs of Lima | Basilica and Convent of St. Francis | The extensive underground network was built c. 1600[66] and functioned as a cemetery until 1810,[67] with some 25,000 bodies lying within.[68] It was reopened in 1950,[67] currently working as a museum. |  |

| Church and Monastery of the Immaculate Conception | Av. Abancay & Jr. Huallaga | Originally founded in 1573, it was once one of the largest and most important in the city, although it has been modified as its terrain was reduced over time, most notably to build a supermarket during the 19th century and then due to the widening of Abancay street. The current church building dates back to the late 17th century, the work of Fr. Diego Maroto.[69] |  |

| Church and Monastery of Saint Rose of the Nuns | Jr. Ayacucho & Sta. Rosa | Built in the 17th and 18th centuries, it consists of the church and monastery next to the house in which Saint Rose of Lima lived and spent the last three months of her life until her death in her room on August 24, 1617. Said room has since been converted into a chapel.[70] |  |

| Church of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph | Jr. Camaná & Moquegua | Built in 1678,[71] it functioned as a shelter for orphaned and abandoned youth owned by a couple, eventually becoming a religious complex through donations. |  |

| Church of the Tabernacle | Jr. Carabaya 220 | Also known as the Sagrario Metropolitano de Lima, it is located between the Archbishop's Palace and the Cathedral. It dates back to 1665 and hosts a large number of records within its archive. |  |

| Church of Saint Anne | Italy Square | Named after the former hospital, it is one of two candidates for the location of Rímac, the oracle that give the city its name. It gave the adjacent square its name until 1910, when it was renamed in honour of a statue to Antonio Raimondi, an Italian–Peruvian geographer and scientist. |  |

| Church of Saint Camillus | Jr. Áncash & Paruro | Named after the order based there, it was rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake and currently houses a health centre. Inside of the church is a statue by Juan Martínez Montañés.[72] |  |

| Church of the Sacred Heart | Jr. Azángaro 776 | Rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake, it was inaugurated on April 6, 1766. It is the only Catholic temple in Peru and Latin America with an elliptical plan, similar to those of Austria, and is designed in the Rococo limeño style. |  |

| Church of Saint Lazarus | Av. Francisco Pizarro & Jr. Trujillo | Built in 1586, it was the first church built in the area. Since then it has been rebuilt several times after being damaged due to the many earthquakes the city has experienced. Up until the 19th century, the church gave the neighbourhood of San Lázaro its name, until it separated from Lima District as Rímac District.[73] |  |

| Church of Saint Liberata | Jr. 22 De Agosto 100 | The church was first built in 1716, with the Cruciferous Fathers of Good Death taking charge of its administration from 1745 to 1826. Its name comes from the patron saint of Sigüenza, the hometown of then Viceroy Diego Ladrón de Guevara. |  |

| Church of Saint Sebastian | Jr. Chancay & Ica | It is the third parish to be built in Lima, founded in 1554. Its altarpiece dates back to the 18th century, and its fountain dates back to 1888. |  |

| Church of the Trinitarians | Jr. Áncash 790 | The land was originally occupied by the Beaterio de las Trinitarias, which became a convent. The church originated as part of that monastery and was completed in 1722. |  |

| Church of Our Lady of Copacabana | Jr. Chiclayo 400 | Rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake with funds from its resident brotherhood and from local devotees, it is shaped like a Latin cross, with short arms and a dressing room behind the front wall. |  |

| Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel | Jr. Junín & Huánuco | The church was originally established as a retreat for poor girls at the beginning of the 17th century, becoming a monastery in 1625. The restoration works that followed the earthquakes 1687 and 1940 made major changes in its floor plan. |  |

| Church of Our Lady of Patronage | Jr. Manco Cápac 164 | The beguinage and the first chapel were completed in 1688, while the temple as a whole was only completed in 1754. In 1919, the beguinage was transformed into the convent of the Dominican nuns of the Most Holy Rosary. |  |

| Church of Our Lady of the Rosary | Jr. Trujillo | The 16th-century church is also known as the "Chapel of the Bridge" after the bridge located one block away. It is best known for its 50 m2 area, which makes it the smallest in the country and a popular tourist attraction.[74] |  |

| Church of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary | Av. Garcilaso de la Vega 1131 | Built in 1606, it had to be restored after the earthquakes of 1687 and 1746, and a fire in 1868.[75] A statue donated by the city's French colony was placed in the public square in front of the church as part of the centennial celebrations of 1921. |  |

| Church of Saint Marcellus | Av. Emancipación & Jr. Rufino Torrico | The church dates back to 1551, being one of the oldest in the city. It was granted the title of parish by Saint Turibius of Mogrovejo thirty-four years after the arrival of the Augustinians.[76] A small square of the same name is located across the street. |  |

| Club Nacional | Plaza San Martín | Founded on October 19, 1855, it has been the meeting place for the Peruvian aristocracy throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, as its members are members of the most distinguished and wealthy families in the country. |  |

| Club de la Unión | Jr. Unión 364 | Founded on October 10, 1868, it is headquartered at the palace of the same name, itself inaugurated in 1942. Its founders include notable historical figures of the history of Peru, many of which served during the War of the Pacific. |  |

| Convent of Our Lady of the Angels | Alameda de los Descalzos | The convent was founded in 1595 by the Franciscan Order and under the auspices of Archbishop Toribio de Mogrovejo. In 1981, a museum was opened in its premises. |  |

| Convent of the Venturous Mary Magdalene | Plaza Francia | Ownership of the Dominican convent passed on to the Charity of Lima after Peru's independence. The Pontifical Catholic University of Peru was inaugurated in this building, and its first classes were dictated in the same place.[77][78] |  |

| Diario El Comercio | Jr. Lampa & Santa Rosa | The building, which houses the newspaper of the same name, is located at the site of a single-storey building that also served as the headquarters of the newspaper, which was burned down by a mob in 1919 alongside the director's residence. It was rebuilt from 1921 to 1924 with a new fortress-inspired design. |  |

| Edificio Aldabas-Melchormalo | Jr. Azángaro & Huallaga | Also known simply as the Edificio Aldabas, the Art Deco building dates back to 1933. |  |

| Edificio Atlas | Jr. Huancavelica & Caylloma | Built for an insurance company of the same name, it won the Gold Medal from the Municipality of Lima for Best Building of 1955, awarded on the Fiestas Patrias. |  |

| Edificio Belén | Av. Uruguay & Jr. Camaná | The Tambo de Belén, one of the first buildings in the country, was designed by Rafael Marquina y Bueno built in 1930. A residential building, it was the home to figures such as Honorio Delgado.[79] It was one of many buildings restored by real estate company Arte Express.[9] |  |

| Edificio Beytia | Jr. Azángaro & Ucayali | The multi-purpose building once served as one of the sites of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[80] |  |

| Edificio Boza | Plaza San Martín | The neo-colonial building was designed by José Álvarez-Calderón and Emilio Harth Terré. It was inaugurated in the 1930s and is one of the largest buildings that surround the public square. |  |

| Edificio Cine Metro | Plaza San Martín | A project by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, it was designed by architect José Álvarez Calderón (with contributions by Guillermo Payet and Schimanetz Fernando) and inaugurated in May 1936 with a capacity of 1390 people. It was renovated in 1956 to install an air conditioning system and ultimately closed in 2000.[81] |  |

| Edificio de la Compañía Peruana de Teléfonos | Jr. Santa Rosa 159 | The building was made to house the telephone company of the same name. Polish–Peruvian architect Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski oversaw the modernisation of the façade in 1929. It is currently owned by Arte Express. |  |

| Edificio El Buque | Jr. Junín & Cangallo | Named after its resemblance to a ship, it was built in the 19th century in a 1,131 m² plot. Originally sporting marble staircases with bronze handrails and wooden balconies, it was built with the purpose of being the first housing complex after independence, being able to house 70 families in total. It has since been declared inhabitable, the result of a series of fires in 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2022 that neighbours blame on the drug addicts that sneak into the building through a hole made in a wall.[82] |  |

| Edificio Encarnación | Jr. Apurímac 224 & Carabaya | The area was originally the location of a monastery of the same name, the first to be founded in the city, on March 25, 1558. The city's growth led to its reduction in size, and eventually its move to Brazil Avenue after it was irreparably damaged by the 1940 earthquake and the fire it caused.[83] The building itself dates back to 1947, when it was commissioned by the Compañía de Seguros Italia to be built by Flores y Costa SA. The cabaret in its basement, known as the Embassy, was one of its best-known features.[84] It is currently owned by Arte Express.[9] |  |

| Edificio Fénix | Av. Colmena & Jr. Carabaya | The building was built in 1934 to house La Fénix Peruana, an insurance company, in the terrain formerly occupied by the Monastery of the Incarnation, after which another building is named. It was acquired by Arte Express in 2005.[9][85] |  |

| Edificio Fernando Belaúnde Terry | Jr. Huallaga 364 | The building, a property of the National Congress, houses the a bookstore in its entrance and the Library of Congress of Peru in its basement. |  |

| Edificio Ferrand | Av. Uruguay | The building, designed by Rafael Marquina y Bueno, was where one of the first Ford del Perú S.A. stores in the country was opened, and also served as the residence of the German consul and delegation before relations were severed due to World War II. Therefore, it was the meeting place for people who supported Adolf Hitler and his system of government. Between both buildings is the first block of what would have been known as Paraguay Avenue, whose path would've continued towards the Plaza Bolognesi, but was abandoned.[79] The Ferrand is one of the buildings purchased by Arte Express.[9] |  |

| Edificio Giacoletti | Plaza San Martín | The building dates back to 1912, and originally featured Art Nouveau decorations on its façade, which were removed in the 1940s. A fire burnt down most of the building in 2018.[86] |  |

| Edificio Gildemeister | Jr. Azangaro 235, 259 | Built between 1927 and 1928 by the Compañía General de Construcciones del Perú and designed by Werner Benno Lange, it was one of the first five-storey buildings of the city and had two elevators: the first for the owner and the second for the rest of its occupants. It is named after Gildemeister y Cia, the sugar production company based in a mill in La Libertad.[38] |  |

| Edificio Guardia Real | Plaza Mayor | One of the buildings that surround the main square of the city, its façade was modified alongside the rest of the buildings to the south and west of the square during the early 20th century. |  |

| Edificio Italia | Jr. Sta. Rosa 191 | The building is named after the Compañía de Seguros Italia, an insurance company, who commissioned its construction to Fred T. Ley's construction firm.[87] It is one of several buildings owned by Arte Express.[9] |  |

| Edificio Javier Alzamora Valdez | Av. Abancay & Colmena | Formerly the headquarters of the Ministry of Education, it's the main location of the Superior Court of Justice of Lima, part of the Judiciary of Peru.[88] It also houses a theatre named after Felipe Pardo y Aliaga. |  |

| Edificio Jesús Nazareno | Jr. Sta. Rosa | Built during the 20th century, the multi-purpose building houses a number of stores, private residences and a McDonald's restaurant. |  |

| Edificio Mercury | Jr. Sta. Rosa | Built during the 20th century, it currently serves as an office building for the Ministry of Economy and Finance. |  |

| Edificio Ostolaza | Av. Tacna & Jr. Huancavelica | The multi-purpose building was designed by architect Enrique Seoane Ros in 1951 and completed in 1953. It received the Chavín Award upon its completion.[89][90] |  |

| Edificio Rímac III | Jr. Sta. Rosa | The multi-purpose building houses a number of offices, including those of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. | — |

| Edificio San Demetrio | Jr. Ocoña 160 | The building was designed by architect José Álvarez Calderón in 1946 and built by the construction firm of R. Vargas Prada and Guillermo Payet. The building is named after San Demetrio SA, the company that commissioned its construction.[91] It is one of several buildings owned by Arte Express.[9] |  |

| Edificio San Luis | Av. Wilson | The building dates back to the late 1930s. Its abandonment led to its acquisition and restoration by Scipion Real Estate, who intend to build a modern construction in the area next to the original building, known as Zepita after the street of the same name.[92][93] |  |

| Edificio Sudamérica | Plaza San Martín | The office building, named after insurance firm Seguros La Sudamericana, was designed by architect José Álvarez Calderón and built by construction firm Fred T. Ley y Cía, being inaugurated in 1941.[94] It is one of several buildings owned by Arte Express.[9] |  |

| Edificio Wiese | Jr. Carabaya 501-515 | Also known as the Casa Wiese, the six-storey neoclassical building dates back to 1922. It is currently owned by Arte Express, who worked on the Urban Hall, an establishment located at the building's corner with the Jirón Santa Rosa.[9] It is named after Augusto Wiese de Osma, the businessman who commissioned its construction.[95] |  |

| Equestrian statue of Francisco Pizarro | Pasaje Santa Rosa | The statue of the Spanish Conquistador was donated by the widow of its sculptor and inaugurated in 1935, as part of the city's fourth centennial celebrations. Originally located next to the Cathedral,[96] it was moved to the Plaza Pizarro in 1952,[97] and finally to the Parque de La Muralla in 2003 without its pedestal. In 2025, it was again returned next to the Plaza Mayor prior to the city's 490th anniversary.[98] |  |

| Government Palace | Jr. Junín | Originally built to be the residence of Francisco Pizarro, it was rebuilt under the presidency of Oscar R. Benavides by architects Claude Sahut and Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski, with construction works finishing in 1937. The palace currently serves as the residence of the President of the Republic, and features a memorial obelisk at its entrance. |  |

| Gran Hotel Bolívar | Plaza San Martín | Part of a program to modernise Lima, the hotel was constructed on what was state property. The hotel was inaugurated on December 6, 1924, as part of the centennial celebrations commemorating the Battle of Ayacucho. |  |

| Hotel Comercio | Jr. Áncash & Carabaya | The hotel, located next to Government Palace, is best known for a murder that took place on June 24, 1930,[99] and for the Bar Cordano, located on its first floor and visited by almost every president since its inception.[100] |  |

| Hotel Maury | Jr. Carabaya & Ucayali | A three-star hotel, it is considered one of the oldest hotels in both Peru and the Pacific coast, having been founded in 1835. It was rebuilt in 1945, giving the building its current modernist appearance. |  |

| Jurado Nacional de Elecciones | Av. Nicolás de Piérola 1080 | The headquarters of the government organisation, it features a museum dedicated to the electoral history of Peru in the 19th and 20th centuries. |  |

| La Prensa | Baquíjano 745 | The building housed the newspaper of the same name, which did not survive the economic crisis of the 1980s. The building was subsequently sold to Supermercados Monterey, a local supermarket chain, in 1986. After its closure in 1993, it became a commercial building. |  |

| Legislative Palace | Plaza Bolívar | Built during the presidency of Óscar R. Benavides on the site of one of the buildings once occupied by the University of San Marcos, it started hosting the Congress of Peru in 1938. |  |

| Lima Stock Exchange Building | Jr. Carabaya & Sta. Rosa | The building, inaugurated in 1950, housed the Lima Stock Exchange from 1997 to 2022 until its acquisition by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which has since repurposed the building. |  |

| Maternidad de Lima | Jr. Sta. Rosa 941 | The maternity hospital was established through a supreme decree on October 10, 1826, moving to its current location in 1934 after a series of location changes. |  |

| Metropolitan Cathedral | Jr. Carabaya & Huallaga | Built alongside the city in 1535, its current form was built between 1602 and 1797, and is dedicated to John the Apostle. Its interior features a gold-plated altar, as well as the tomb of Francisco Pizarro. A Te Deum mass is traditionally held annually as part of the national day celebrations. Another custom restarted by Cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani, is to celebrate mass every Sunday at 11:00 a.m. In 2005, Mayor Luis Castañeda oversaw a project of illuminating the exterior of the cathedral with new lights. |  |

| Monastery of Saint Clare | Jr. Jauja 449 | The first building is from 1606, but the current temple is from the 19th century, occupying a large part of the extensive block in which it is located. A former mill of the same name is located across the street from the monastery. |  |

| Municipal Palace | Jr. Unión | Built in 1939, the building serves as the city hall, housing the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima. |  |

| Museo Central | Jr. Lampa & Ucayali | The building is located on land acquired by the Central Reserve Bank of Peru in 1922 to occupy the bank's first premises, inaugurated on January 2, 1929. It currently functions as a museum and art centre. |  |

| Museo del Congreso y la inquisición | Jr. Junín 548 | Located in the neighbourhood of Barrios Altos, the building served as the former headquarters of the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and later as the seat of the Peruvian Senate until 1939. The museum dedicated to both occupants was opened on July 26, 1968. |  |

| National Agrarian Confederation | Jr. Sta. Rosa 327 | The modern building houses the organisation of the name name, created in 1974 in the aftermath of the Peruvian Agrarian Reform by peasants who supported the measure. |  |

| National Library of Peru | Av. Abancay | Founded by José de San Martín in 1821, it was looted during the military occupation of the city during the War of the Pacific and was almost completely destroyed in a fire on May 10, 1943. It has since been restored and is open to the public. |  |

| Old San Bartolomé Hospital | Jr. Sta. Rosa | The former premises of San Bartolomé Hospital were in use from its foundation in 1651 until 1988, when it was moved to its current site in Alfonso Ugarte Avenue. |  |

| Pasaje Olaya | The pedestrian alleyway is named after José Olaya, who was executed by firing squad for being a spy for pro-Independence forces on June 29, 1823. |  | |

| Pasaje Santa Rosa | The pedestrian alleyway is named after Saint Rose of Lima. It features a memorial to the last kuraka of Lima since 1985. It serves as a space for public displays. |  | |

| Paseo de Aguas | Rímac District | It was built between 1770 and 1776 by Viceroy Manuel de Amat y Juniet and inaugurated in a reduced scale from what was originally planned. During the 1950s, it was the site of a local festival and it has since been restored. |  |

| Pinacotheca of Lima | Plaza Francia | The museum was inaugurated in 1925, under the presidency of Augusto B. Leguía and under the mayoralty of Pedro José Rada y Gamio. Located at the former Hospicio Bartolomé Manrique, it is named after Peruvian painter Ignacio Merino, and also serves as the largest collection of his paintings. |  |

| Plaza Bolívar | Formerly known as the site of the Tribunal of the Inquisition, it has been extensively modified throughout its history and currently houses an equestrian statue of Simón Bolívar and a tomb to an unknown soldier. |  | |

| Plaza de la Democracia | Since 2006, it is located on the former site of the Bank of the Nation Building designed by Enrique Seoane Ros, which burned down in the year 2000 during the Four Quarters March.[101] Its former address is Av. Nicolás de Piérola 1045. |  | |

| Plaza Italia | Barrios Altos | Formerly known as Saint Anne's Square, it was the second square built by the Spanish during the colonial era and later served as one of the four squares where the independence of Peru was declared in the city. |  |

| Plaza Luis Alberto Sánchez | Av. Nicolás de Piérola | Located across the street from the park of the University of San Marcos, it is named after the APRA politician who served as the university's rector three times. It is also known as "Culture Park" (Parque de la Cultura).[102] |  |

| Plaza Mayor | The site of the foundation of the city, it also served as the location of one of José de San Martín's proclamations of the independence of Peru in 1821.[24] |  | |

| Plaza Perú | Jr. Conde de Superunda & Unión | The site was originally the site of the residence of a brother of Francisco Pizarro, eventually becoming a square in Pizarro's honour featuring an equestrian statue of his that was moved from the Cathedral in 1952. The statue was again moved in 2003, with the square acquiring its current appearance soon after. |  |

| Plaza San Martín | The square was built to coincide with the centennial celebrations that took place in 1921, having replaced a train station and featuring an equestrial monument to José de San Martín, the work of Spanish sculptor Mariano Benlliure. |  | |

| Quinta Heeren | Barrios Altos | Originally named after the nearby church of the same name, it is named after Óscar Heeren. From 1901 to 1940, the quinta was the headquarters of the embassies of Japan, Belgium, Germany, France and the United States.[82] |  |

| Royal Hospital of Saint Andrew | Jr. Huallaga 846 | The first hospital in both the country and South America,[103] it is also linked to the National University of San Marcos and its early history of healthcare studies in Peru, and once housed a number of mummies of the Inca Empire's nobility, including that of Pachacuti.[103] |  |

| Sanctuary and Monastery of the Holy Trinity | Jr. Cuzco 340 | Dating back to 1584, it was the second large establishment of its type established in the city, founded by Lucrecia de Sánsolas. As with other buildings in the city, it had to be restored after the earthquake of 1746. During the 20th century, it was again intervened, although this time its size was reduced. |  |

| Sanctuary and Monastery of Las Nazarenas | Av. Tacna & Jr. Huancavelica | The complex was built during the 18th century after the original building had to be demolished as it was irreparably damaged during the earthquake of 1746. It is the location of the Lord of Miracles, an icon venerated by local Catholics during festivities that take place every October. |  |

| Sanctuary of Saint Rose of Lima | Av. Tacna | Inaugurated in 1992, it's located in the remains of Saint Rose of Lima's house, including the well used by her family. It is therefore also the location of the miracles attributed to her. |  |

| Stone of Taulichusco | Pasaje Santa Rosa | Since 1985, the stone serves as a memorial to Taulichusco, the last Kuraka of Rímac Valley prior to the arrival of the Spanish. |  |

| Teatro Colón | Plaza San Martín | Its construction began in 1911, being inaugurated on January 18, 1914. Until the 1980s, the theatre functioned normally until it became and started airing adult films, being ultimately closed in 2000. Five years later, an NGO aimed at rehabilitating the building began operating. |  |

| Teatro Municipal | Jirón Ica | The home to the country's National Symphony Orchestra, it was inaugurated on July 28, 1920. It was bought by the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima in 1929 and renamed to its current name through a Mayor's Resolution of June 15 of that year. Damaged in a fire in 1988, it has since been restored and reopened to the public. |  |

| Teatro Segura | Jirón Huancavelica | First built in 1615, it is considered the oldest theatre in Latin America. This original open-air theatre was destroyed by an earthquake in 1746 and rebuilt a year later. The theatre was later reformed in 1822 and 1874. The actual construction was built in 1909 under the name of "Teatro Municipal". The name was changed in 1929 to "Teatro Manuel Ascencio Segura". Among its premises is a theatre museum. |  |

| Telefónica del Perú | Av. Nicolás de Piérola & Jr. Contumazá | The building was designed by José Álvarez Calderón in 1938 and inaugurated in 1940, housing the company of the same name. Its design was inspired by its counterpart in Madrid.[9] It was purchased in 2021 by Arte Express at a cost of S/. 10.6 million (around €2.4 million),[104] who agreed to allow that the first third floors continue to be used by its original owner, in order to rent its different floors to different state-owned institutions.[9] |  |

| Torre Tagle Palace | Jr. Ucayali 363 | Built during the early 18th century using materials from Spain, Panama and other Central American countries,[105] it was purchased by the government in 1918 and currently serves as the main headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. |  |

| University of San Marcos Campus and adjacent park | Av. Colmena 1222 | Formerly a Jesuit novitiate, the building and park are the property of the University of San Marcos, where its cultural centre and crypt are located. The park was built in 1870, with a clock tower being built by the German colony as part of the centennial celebrations in 1921. At noon, their bells play notes of the national anthem. |  |

| University of San Marcos' Royal College | Jr. Andahuaylas 348 | Formerly known as Royal College of San Felipe, it dates back to the Spanish era, having housed a military barracks and an art school before currently housing three departments of the university. |  |

| Walls of Lima | Parque de la Muralla | Formerly surrounding what is now known as the Cercado de Lima, a few remains can be seen at the park that runs alongside the Rímac River. | |

Landmarks included within the buffer zone of the World Heritage Site

| |||

| Chinatown | Jr. Ucayali, blocks 7 & 8 | The neighborhood was founded in the mid-19th century by Chinese immigrants, but it was heavily damaged in the late 19th century by the War of the Pacific and further declined in the following decades. It experienced a revival starting in the 1970s and is now a thriving resource for Chinese-Peruvian culture. Its main feature is the monumental arch at its entrance. |  |

| Casa del Maestro | Paseo Colón | Designed by architect Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski, it was built in 1920 and originally known as the Casa Wiese, as it the residence of banker Augusto Wiese Eslava, who founded the bank named after him.[77] |  |

| Casa Dibos | Av. Nicolás de Piérola & Jr. Cañete | Also known as the Casa Victoria Larco de García,[106] the French-inspired building was designed by Claude Sahut and built in 1908. Its owners were Eduardo Dibos Pflucker and his wife Guillermina Dammert Alarco, the daughter of Juana Alarco de Dammert. The building was one of the first to be built in the new avenue.[106] |  |

| Casa García y Lastres | Av. Nicolás de Piérola 412 & Jr. Chancay | Named after its owner, it was designed by Claude Sahut and built in 1915.[107] |  |

| Casa Gonzales de Panizo | Av. Nicolás de Piérola & Jr. Cañete | The French-inspired building was designed by Claude Sahut, and currently functions as a children's therapy institute. The building was one of the first to be built in the new avenue.[106] |  |

| Casa Malachowski[106] | Av. Nicolás de Piérola & Jr. Inclán | The building was designed by Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski and built in 1914. It was purchased in 2013 by Arte Express and named after its architect.[106] |  |

| Casa Mariátegui | Jr. Washington 1946/1938 | The museum is dedicated to the life and work of writer José Carlos Mariátegui, as well as that of his wife Anna Chiappe and partner Victoria Ferrer. Mariátegui moved into the house in 1925, where he spent the final years of his life. |  |

| Casa Matusita | Av. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega 1390 | Dating back to the Spanish era, the house is reportedly haunted, although some conspiracy theories suggest that these urban legends were disseminated by the CIA to prevent the building's use for espionage, due to the fact that the U.S. embassy was located across the street at the time. |  |

| Casa Menchaca[108] | Av. 9 de Diciembre 209 | The house was built in 1920 and designed by French architect Claude Sahut. Known for its azulejos, it served as the diplomatic mission of the Empire of Japan prior to World War II.[109] |  |

| Casa Molina | Av. 9 de Diciembre & Wilson | Named after its owner, Dr. Wenceslao Molina,[110] It was designed by French architect Claude Sahut and dates back to 1912.[111] |  |

| Casa Ostolaza | Av. Nicolás de Piérola & Tacna | The building was built in the early 20th century for the Porvenir insurance company. It was purchased in 2013 by Arte Express and annexed to two other homes and an terrain, being thus renamed the Edificio Popular y Porvenir.[106] It currently houses a supermarket.[112] |  |

| Casa del Pueblo | Av. Alfonso Ugarte 1012 | The building serves as the main headquarters of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance, a political party. In addition to its political functions, it also provides social services, incling education, healthcare and soup kitchen. |  |

| Casa Sal y Rosas | Paseo Colón & Jr. Washington | Designed in 1912 by Víctor Mora, it was inaugurated five years later. It owes its name to Francisco Sal y Rosas Valega, one of its owners, whose widow, Ignacia Rodulfo López Gallo, inherited the house. In this place the owner married General César Canevaro, Peruvian hero of the War of the Pacific. |  |

| Cementerio Presbítero Maestro | Jirón Áncash | Inaugurated on May 31, 1808, it is the oldest cemetery in the city. It functions as a museum, housing some of the most important characters of the city and country's history, with 766 mausoleums and 92 historical monuments in total. |  |

| Cementerio El Ángel | Jirón Áncash | It was inaugurated on June 27, 1959, due to the need of the city to have a new funerary space, since the capacity of the main cemetery had reached its maximum in 1955. It also houses a number of important figures of the city's history. |  |

| Centre for Military Historical Studies | Av. 9 de Diciembre 150 | Originally the Peruvian Pavilion at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, it was disassembled and rebuilt in Peru. It housed the National Institute of Hygiene and later a Traffic Command until 1960, when it was donated to the Armed Forces. |  |

| Church of Our Lady of Cocharcas | Jr. Huánuco & Puno | The church building was first built as a chapel by Sebastián Alonso in 1864. Its current Baroque façade dates back to the 18th century, having been last modified in 1994, when its structure was expanded.[113] |  |

| Church of Our Lady of Monserrate | Jr. Callao & Tayacaja | Originally a Benedictine hospice founded in 1601, it is located in the street through which the Viceroys ceremonially entered Lima. As such, it served as the resting place for the Viceroy Prince of Squillace prior to his entrance to the city.[114] |  |

| Church of Saint Catherine of Siena | Barrios Altos | The church's construction dates back to 1589, when attempts were made by María de Celis to establish a monastery by requesting a licence which was granted but did not materialise due to her death. Her efforts were continued by Saint Rose of Lima starting in 1607, with the complex completed in 1624, some years after her death. |  |

| Cine Grau | Av. Grau | The Art Deco building, once one of the city's traditional movie theatres, was closed by the authorities of La Victoria District due to the illegal prostitution taking place within its premises.[115][116] |  |

| Cine Ritz | Av. Alfonso Ugarte 1437 | The movie theatre was originally inaugurated in 1935 as a regular cinema. In 2022, it was closed by the municipal authorities for illegally showing adult films.[117][118] |  |

| Cine Tacna | Av. Tacna & Jr. Moquegua | The building of the same name was designed by Alejandro Alva Manfredi,[119][120] and its movie theatre opened in April 1948 under the auspices of Paramount International Corporation Teatros, operating until 2006.[81] |  |

| Cine Tauro | Jr. Washington | The defunct movie theatre, originally planned as a multi-purpose building, was built in 1959 by Peruvian architect Walter Weberhofer. The theatre started showing pornographic films the 1990s and has been thus temporarily closed on several occasions. |  |

| Cine Teatro Conde de Lemos | Jr. Huánuco 889 | The first theatre of Barrios Altos, it was inaugurated in 1948 next to the Plaza Buenos Aires,[121] in the former premises of San José alleyway and functioned until 1995.[122] It was acquired by the city's municipality, who repurposed the building as a neighbourhood unit in 2022, with cultural, recreational and medical services within its premises.[123][124] | — |

| Colegio de la Inmaculada | Av. Nicolás de Piérola 351 | The early 20th-century building that currently houses Federico Villarreal National University originally housed the private Catholic school until 1967, when it moved to its current premises in La Molina District. |  |

| College of Our Lady of Guadalupe | Avenida Alfonso Ugarte | The college has played an important function in the doctrinal, intellectual and political life of Peru, such as during the War of the Pacific. Many of its alumni have stood out in different professional fields. |  |

| Comisaría El Sexto | Avenida Alfonso Ugarte | Formerly a prison, it is operated by the National Police of Peru since 1986. Within its premises is an organised collection of items of the Peruvian conflict. |  |

| Cuartel Barbones | Barrios Altos | Originally located next to the city gate named after it, it was originally established as an Indian hospital of the Bethlehemite Brothers that was destroyed during the earthquake of 1687. After independence, it was repurposed into a military barracks. | — |

| Edificio Cooperativa Santa Elisa | Jr. Caylloma | Formerly the headquarters of the Cooperativa de Ahorro y Crédito Santa Elisa, it was abandoned during the late 20th century, becoming a meeting point what was then the Peruvian counterculture. A fire spread through the building in 2018,[125] and it was later acquired by Arte Express,[9] who planned to restore the building by 2021,[126] but this has not taken place due to the squatters that occupy the building.[127] |  |

| Edificio Crillón | Av. Nicolás de Piérola 589 | Currently an office building, it hosted one of the most emblematic hotels in the city from 1947 until 1999, hosting well-known figures of the era, including foreign actors and musicians. |  |

| Edificio Ferrand (1948) |

Av. Wilson | The eight-storey building was designed by architects Fernando Belaúnde Terry and Alejandro Alva Manfredi.[128] It was built opposite of Elguera Square, incorporating its orientation. The International Petroleum Company was based from its second to sixth floors.[129] |  |

| Edificio Manuel Vicente Villarán | Paseo Colón & Jr. Washington | Named after jurist and politician Manuel Vicente Villarán, the building dates back to 1924 and was designed by Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski. |  |

| Edificio República | Paseo de los Héroes Navales | Built during the 1940s, it was the first building of its kind to be built in Lima. When it first opened, its first floor was occupied by shops, the second to fifth floor by offices, and the final three floors by apartments.[130] Its air conditioning system was manufactured by Carrier Corporation and installed by Pedro Martinto, S.A.[130] Until 1974, it housed the embassy of the United Kingdom on its fifth floor.[131] |  |

| Edificio Rímac | Av. Roosevelt 101/157 & Jr. Unión 1177/1199 | Designed by architect Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski, it was the first multi-family building in the city and also where one of its first Otis elevators was installed. It was owned by Manuel Prado Ugarteche between 1939 and 1945. |  |

| Edificio Rizo Patrón | Av. Colmena & Wilson | The building was designed by architect Enrique Seoane Ros and inaugurated during the late 1940s. |  |

| Edificio de la Sociedad de Ingenieros | Av. Nicolás de Piérola & Jr. Camaná | The building was made in 1924 to house the Peruvian Engineers Association. Its construction took place under the supervision of Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski.[132] |  |

| Edificio Tacna-Colmena | Av. Colmena & Tacna | This 23-story building, topped by a private access penthouse with a pool, was built from 1959 to 1960, the first to have anti-seismic features in the country. It housed a cinema and a bank on its first floor, and was the residence of Mariano Prado, son of former president Manuel Prado Ugarteche. |  |

| Edificio Wilson | Plaza Elguera | Designed by Enrique Seoane Ros, it was built from 1945 to 1946. The modernist building currently has a commercial and residential use.[133][134] |  |

| Fort of Santa Catalina | Jr. Inambari 790 | The fort is one of the few remaining examples of military viceregal architecture that continues to exist in Peru. Built at the beginning of the 19th century, it served as the barracks for the artillery units of the army and the police forces. |  |

| Hospital Arzobispo Loayza | Av. Alfonso Ugarte 848 | Founded in 1549 in Barrios Altos as a hospital for local Indians, it moved to its current premises in 1924, the work of Claude Sahut. |  |

| Hospital Dos de Mayo | Avenida Miguel Grau | It is considered the first hospital of the republican history of the country, and was preceded by the Royal Hospital of Saint Andrew, itself the oldest hospital of the Viceroyalty of Peru.[103] |  |

| Hospital San Bartolomé | Av. Alfonso Ugarte 825 | It was founded during the viceregal era, to care for freed blacks. In 1961 it was transformed into a maternal and children's hospital, moving to its current location in 1988. |  |

| Hotel Savoy | Jr. Callao & Caylloma | Designed by Italian architect Mario Bianco Zanaldo,[135][136] construction took place between 1954 and 1957 on the property owned by Jewish-Peruvian textile businessmen Isaac and José Varón Eskenazi.[136] It became known as the "bullfighter's hotel" due to the fact that said performers usually stayed there when visiting the city to perform in Acho.[136] Its attendance declined starting in the 1980s due to the economic crisis and subsequent armed conflict, eventually declaring bankruptcy and closing its doors in 1992.[136][137] |  |

| Lima Civic Center & Sheraton Lima Historic Center | Paseo de los Héroes Navales | A complex composed of a multi-purpose building, a hotel and a shopping centre, it was built on top of the former grounds of the Lima Penitentiary, demolished in the 1960s. At 109 meters tall, its tower was the tallest building in the country for 34 years. |  |

| Maison de Santé | Jr. Miguel Aljovin 222 | The hospital was inaugurated on August 15, 1867, by Edmond de Lesseps, then French consul to Peru. It replaced a convent in what was then Mapiri street.[138] |  |

| Mercado La Aurora | Av. Emancipación 668, Jr. Cañete 473 & Jr. Huancavelica 670 | Located in the Monserrate neighbourhood, it was originally a garden that was popular with the locals and owned by the adjacent monastery. The market dates back to the early 20th century. |  |

| Mesa Redonda | Barrios Altos | The area is a popular shopping centre surrounded by Huanta and Cuzco streets, as well as Abancay and Colmena avenues.[139] Known for its informality, its the site of a number of fires, notably that of 2001. |  |

| Museo de Arte italiano | P.° de la República 250 | The only European arts museum of Peru, it was the gift from the Italian colony to the city as part of the centennial celebrations that took place in 1921. Designed by architect Gaetano Moretti, it was inaugurated on November 11 of the same year. |  |

| Museo Metropolitano | Av. 28 July & Wilson | The neoclassical building that houses the museum was designed by French architect Claude Sahut and built in 1924, formerly housing the country's Ministry of Development and Public Works.[140] It was inaugurated on October 10, 2010.[141][142] |  |

| Museo Nacional de la Cultura Peruana | Avenida Alfonso Ugarte | It was founded on March 30, 1946, by the Peruvian historian, anthropologist and indigenist Luis E. Valcárcel. It houses 1,500 pieces, most of which date from the 20th century. The collection includes imagery from Cuzco, mates from Huanta and altarpieces from Ayacucho.[143][144] It was designed in Neo-Inca style by architect Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski.[145] |  |

| Mogrovejo Hospital | Jr. Áncash 1271 | Founded in the viceregal era with a Royal Decree of August 26, 1700, as the "Refuge for Incurables", it is currently an institute for neurology and features a museum dedicated to the human brain. |  |

| Palace of the Exhibition | Paseo Colón | Built for the Lima International Exhibition in 1872, it has housed a number of government entities and currently hosts the Lima Art Museum since 1957. | |

| Palace of Justice | Paseo de los Héroes Navales | The Palace was built in a neoclassical style as its plans were based on those of the Law Courts of Brussels, Belgium, work of Joseph Poelaert. However, it lacks the dome of its Belgian counterpart. |  |

| Parque de la Exposición | Santa Beatriz | Built for the Lima International Exhibition in 1872, it features buildings that were used as pavillions (with Byzantine, Gothic and Seismographic themes) during the event, an open-air amphitheatre, a theatre building, a bust of Fernando Belaúnde, duck ponds and fountains (dedicated to racial harmony, a Roman god and Ricardo Palma). |  |

| Paseo de los Héroes Navales | Built in the 1920s under the government of President Augusto B. Leguía, it was given its current name on October 8, 1979 in commemoration of the centenary of the battle of Angamos. It features a number of landmarks on its immediate surroundings, as well as a number statues on its premises, notably La yunta and Las llamas. |  | |

| Public Ministry of Peru | Avenida Abancay | The building was built in 1952, during the government of Manuel Odría, and is the work of architect Guillermo Payet, who conceived the design according to the modernist movement, occupying an entire block of the avenue at the time of its widening.[146][147] |  |

| Plaza Dos de Mayo | The square was built in 1874 by the Peruvian government to commemorate the Battle of Callao, which took place off the coast of Callao on May 2, 1866, between the navies of Peru and Spain. It serves as the intersection of Colonial, Alfonso Ugarte and Colmena avenues. |  | |

| Plaza Grau | Paseo de la República | It is located at the intersection of the Paseo de la República with the Paseo Colón, Miguel Grau Avenue and the Paseo de los Héroes Navales. Named after Miguel Grau Seminario, the square's monument is dedicated to him. |  |

| Plaza Ramón Castilla | Avenida Alfonso Ugarte | One of three squares in the avenue, a monument dedicated to Ramón Castilla overlooks the square, inaugurated on May 17, 1969. |  |

| Plazuela Aramburú | Jr. Azángaro & Manuel Aljovín | The square is one of the oldest in the city, once a garden belonging to Alonso Ramos Cervantes and his wife, Elvira de la Serna. It was previously known as "Plazuela de Guadalupe" after the church of the same name that was repurposed and eventually demolished in order to build the Palace of Justice.[148] |  |

| Plazuela Federico Elguera | Av. Wilson & Jr. Quilca | Originally named "Salud" after a train station of the same name, it is named after politician Federico Elguera, whose monument is located in the middle of the square. When the city walls still existed, it was located next to one of the gates and was a gathering place for fishermen that came from Callao to sell their products. In addition to the monument, it also features a cross dedicated to the men shot during the occupation of Lima.[149] |  |

| Plazuela Monserrate | Jr. Callao & Tayacaja | The small area serves as the main square of the neighbourhood of the same name, traditionally a focal point of Peru's creole music.[150] |  |

| Quinta Alania | Paseo Colón | Designed by French architect Emile Robert in 1909, the Art Nouveau building follows a T-shaped path and serves as a condominium.[151][152] It was built alongside the avenue as part of the city's expansion programme.[153] |  |

| Quinta Carbone | Barrios Altos | Built on the former grounds of the Chirimoyo orchard, it was built during the early 20th century as a housing project. It features a chapel built in 1922 dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.[154] | — |

| School of Arts and Crafts | Av. Miguel Grau 620 | Built to house the school of the same name, it was inaugurated on September 24, 1905, during an important ceremony. It became a polytechnic in 1951, and is known as the "José Pardo Technological Institute" since 1983.[155][156] |  |

Ancient Reduction of Santiago Apostle of Cercado

[edit]The Ancient Reduction of Santiago Apostle of Cercado (10.2 ha) was added to the World Heritage Site in 2023.[2]

List of Landmarks included within the UNESCO World Heritage Site

| |||

| Name | Location | Notes | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alipio Ponce Vásquez Police School | Av. Sebastián Lorente 769 | Founded in the Quinta Cortés as a mental hospital that operated between 1859 and 1918, it was repurposed as a training academy for the Civil Guard, and continues to be used by the National Police of Peru. |  |

| Bastión de Santa Lucía | Jr. José de la Rivera & Dávalos 491-499 | One of the few remains of the walls of Lima, preserved better than the other remains.[157] | — |

| Cinco esquinas (partial) | In the 19th century, it was a place where Lima's bohemians gathered, becoming a refuge for criminals the following century.[158] It is located at the intersection of Junín, Miró Quesada and Huari streets. It inspired Mario Vargas Llosa's novel of the same name.[159] | — | |

| Santiago Apóstol del Cercado | Jr. Conchucos 720 | Rebuilt after the 1746 earthquake, the barroque church was again affected by the 1940 Lima earthquake, being restored by Emilio Harth-Terré and Alejandro Alva. A figure of the Virgin of Carmel was enshrined in the church during a ceremony attended by then president Augusto B. Leguía on July 16, 1921.[160] |  |

| Plazuela del Cercado | Originally an Indian reduction,[b] it is unique in the continent, as it has a rhomboid shape.[162] | ||

| Santo Cristo de las Maravillas | Av. Sebastián Lorente & Jr. Áncash | Named after the devotion of the same name,[163] it was originally located in front of one of the city gates, which took its name from the church.[164] It was the old starting point for funeral processions to the General Cemetery of Lima, given its location, which precedes the cemetery's foundation in 1808.[163] |  |

Quinta and Molino de Presa

[edit]The Quinta and Molino de Presa (1.62 ha) were added to the World Heritage Site in 2023.[2]

List of Landmarks included within the UNESCO World Heritage Site

| |||

| Name | Location | Notes | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quinta and Molino de Presa | Jr. Chira 344[165] | The 18th century building was built under the government of then viceroy of Peru, Manuel de Amat y Junyent. It comprises a constructed area of 15,159 square metres (163,170 sq ft).[166] |  |

| Callejón de Presa | A passage and street that leads to the Quinta.[167] | — | |

| Plazuela de Presa | The public square outside the Quinta.[168] | — | |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ PROLIMA member Juan Miguel Delgado explains that, although the emblem used by the Blue Shield International (officially represented in Peru by the Comité Peruano del Escudo Azul Peruano since January 30, 2019) is a blue-and-white shield, a different colour was specifically chosen to contrast with the buildings' façades, with black serving as a neutral alternative to the standard navy blue.[3]

- ^ A population centre in which dispersed indigenous people were grouped, for the purposes of evangelisation and cultural assimilation.[161]

References

[edit]- ^ "Centro Histórico de Lima: Patrimonio Mundial". Sitios del Patrimonio Mundial del Perú.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Historic Centre of Lima". World Heritage Convention. UNESCO.

- ^ Tolentino, Scheila (9 May 2023). "Centro de Lima: ¿por qué algunas edificaciones tienen un escudo blanco y negro? Esta es la razón". La República.

- ^ Martínez Hoyos, Francisco (15 March 2018). "Lima, la joya del virreinato del Perú". La Vanguardia.

- ^ "Centro Histórico de Lima Patrimonio Cultural". UNESCO Cátedra. Universidad de San Martín de Porres.

- ^ Pereyra Colchado, Gladys (27 September 2020). "Los secretos de una Lima subterránea y su relación con el hallazgo en la plazuela San Francisco". El Comercio.

- ^ a b c "La inmortal flor de la canela". ABC. Archived from the original on 19 April 2004.

- ^ Augustin, Reinhard (2017). El Damero de Pizarro: El trazo y la forja de Lima (PDF) (in Spanish). Lima: Municipality of Lima. ISBN 978-9972-726-13-2. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Melgarejo, Víctor (5 April 2021). "Arte Express compra a Telefónica del Perú su antigua sede en el Centro de Lima". Gestión.

- ^ "Arte Express concretaría la compra de 10 edificios en el Cercado de Lima esta semana". El Comercio. 7 November 2018.

- ^ Medrano Marin, Hernán (22 September 2021). "Códigos QR y turismo cultural: la iniciativa para dar a conocer valor histórico de Casa Aliaga, edificio de El Comercio y otros sitios emblemáticos de Lima". El Comercio.

- ^ "Presidenta Boluarte destaca ley que crea régimen especial del Centro Histórico de Lima". El Peruano. 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Lima lanza su patronato con la intención de revalorizar su patrimonio". EFE. La Vanguardia. 17 January 2025.

- ^ Gamarra Galindo, Marco (14 January 2011). "Historia y anécdota del mirador Ingunza". Blog PUCP.

- ^ Calidad en el Museo Palacio Arzobispal (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Ricardo Palma. 2017. pp. 7, 17.

- ^ a b Córdova Tábori, Lili (4 December 2013). "Edificios transformados con el tiempo: De Banco Wiese a supermercado". El Comercio.

- ^ Bonfiglio, Giovanni (1993). Los italianos en la sociedad peruana: una visión histórica (in Spanish). Asociación Italianos del Perú. p. 204.

- ^ "Ex-Banco Italiano". Grid Studio.

- ^ "El Banco Perú y Londres". ArqAndina: El Portal Peruano de Arquitectura.

- ^ "El Edificio del Banco Perú y Londres". Ilustración peruana. Vol. 3, no. 91. 28 June 1911. pp. 1142–1143.

- ^ Bonilla Di Tolla 2009, p. 257.

- ^ Bonilla Di Tolla 2009, p. 189.

- ^ Fhon Bazan, Miguel (12 December 2016). "La antigua Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados". Medium.com. Cultura Para Lima.

- ^ a b Garay, Karina (28 July 2023). "Fiestas Patrias: estas son las 4 plazas de Lima donde se gritó la Independencia".

- ^ "Historia del Banco". Gob.pe. Banco de la Nación. 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Primer Héroe Bombero". Gob.pe. Municipalidad de La Punta. 3 May 2023.

- ^ Salmón Salazar, Gisella (1 February 2010). "Cinco Siglos de Historia: Casa de Aliaga" (PDF). Variedades. pp. 2–4.

- ^ "La Casa Barbieri". Medium.com. Cultura Para Lima. 25 July 2016.

- ^ Deza de la Vega, Natalia (10 January 2017). "La Casa Courret". Medium.com. Cultura Para Lima.

- ^ Coello Rodríguez, Antonio (2016). "Investigaciones histórico-arqueológicas en el antiguo claustro del noviciado, hoy Casa de la Columna, del convento de Santo Domingo de Lima". Boletín de Arqueología PUCP (21).

- ^ Quiroz Galvan, Diana Mery (17 October 2022). "Se inaugura la Casa de la Cultura Criolla, un reconocimiento a Rosa Mercedes Ayarza, autora del clásico "Congorito"". El Comercio.

- ^ Orrego Penagos, Juan Luis (16 July 2011). "Las antiguas calles de Lima". Blog PUCP.

- ^ Salas Pomarino, Jimena (23 March 2020). "Casa de Divorciadas: retorno a la belleza". Revista COSAS.

- ^ Obando, Manoel (18 April 2024). "La Casa Dubois: lo que tiene en común el Central Park de New York y el Jirón de la Unión del Centro de Lima". Infobae.

- ^ Orrego Penagos, Juan Luis (28 December 2009). "La 'casa de piedra' (Lima)". Blog PUCP.

- ^ Malpartida Tabuchi, Jorge (27 July 2017). "Fiestas Patrias: casas de los próceres están en el olvido". El Comercio.

- ^ WMF, CIDAP, AECID, p. 23.

- ^ a b Planas, Enrique. "Las casonas del Centro de Lima". El Comercio.

- ^ "Proyecto de restauración y puesta en valor de la Casa Gutiérrez de Coca: Tradición limeña y modernidad". PROYECTA. Vol. 4, no. 21. 2013. pp. 50–53.

- ^ a b "Arte Express compra casa que perteneció a una de las familias más ricas de la época colonial". Gestión. 19 March 2019.

- ^ Gonzales Obando, Diana (20 February 2023). "Agua Viva: así es el restaurante que fue elegido como el mejor 'huarique' de Lima". El Comercio.

- ^ "La jornada de la "toma de Lima" termina con enfrentamientos y el incendio en un edificio en el centro histórico de la capital peruana". BBC Mundo. 20 January 2023.

- ^ Llerena, Paula; Pacheco Ibarra, Juan José (20 January 2023). "¿Cuál es la historia detrás de la casona que se quemó y derrumbó durante las protestas en Lima?". Trome.