East Germany

This article may require copy editing for awkward phrasing and excessive passive voice. (August 2023) |

German Democratic Republic Deutsche Demokratische Republik (German) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949–1990 | |||||||||

| Motto: "Proletarier aller Länder, vereinigt Euch!" | |||||||||

| Anthem: "Auferstanden aus Ruinen" ("Risen from Ruins") | |||||||||

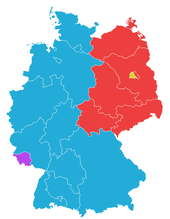

Territory of East Germany (green) in 1957 | |||||||||

| Status | Satellite State of the Soviet Union | ||||||||

| Capital and largest city | East Berlin[a] 52°31′N 13°24′E / 52.517°N 13.400°E | ||||||||

| Official languages | German Sorbian (in parts of Bezirk Dresden and Bezirk Cottbus) | ||||||||

| Religion | See Religion in East Germany | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) |

| ||||||||

| General Secretary | |||||||||

• 1946–1950[b] | Wilhelm Pieck and Otto Grotewohl[c] | ||||||||

• 1950–1971 | Walter Ulbricht | ||||||||

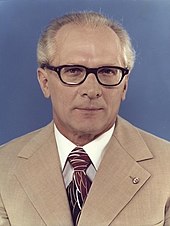

• 1971–1989 | Erich Honecker | ||||||||

• 1989[d] | Egon Krenz | ||||||||

| Head of State | |||||||||

• 1949–1960 (first) | Wilhelm Pieck | ||||||||

• 1990 (last) | Sabine Bergmann-Pohl | ||||||||

| Head of Government | |||||||||

• 1949–1964 (first) | Otto Grotewohl | ||||||||

• 1990 (last) | Lothar de Maizière | ||||||||

| Legislature | Volkskammer | ||||||||

| Länderkammer[e] | |||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

| 7 October 1949 | |||||||||

| 16 June 1953 | |||||||||

| 14 May 1955 | |||||||||

| 4 June 1961 | |||||||||

• Basic Treaty with the FRG | 21 December 1972 | ||||||||

| 18 September 1973 | |||||||||

| 13 October 1989 | |||||||||

| 9 November 1989 | |||||||||

| 12 September 1990 | |||||||||

| 3 October 1990 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 108,875 km2 (42,037 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1950 | 18,388,000[f][1] | ||||||||

• 1970 | 17,068,000 | ||||||||

• 1990 | 16,111,000 | ||||||||

• Density | 149/km2 (385.9/sq mi) | ||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 1989 estimate | ||||||||

• Total | $525.29 billion[2] | ||||||||

• Per capita | $26,631[2] | ||||||||

| HDI (1990 formula) | 0.953[3] very high | ||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||

| Time zone | (UTC+1) | ||||||||

| Drives on | Right | ||||||||

| Calling code | +37 | ||||||||

| Internet TLD | .dd[g][4] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||||

The initial Flag of East Germany (GDR) adopted in 1949 was identical to that of West Germany (FRG). In 1959, government of this country issued a new version of the flag bearing the national emblem, serving to distinguish East from West. | |||||||||

East Germany (German: Ostdeutschland, pronounced [ˈɔstˌdɔʏtʃlant] ⓘ), officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; Deutsche Demokratische Republik, pronounced [ˈdɔʏtʃə demoˈkʁaːtɪʃə ʁepuˈbliːk] ⓘ, DDR), was a country in Central Europe that existed from its formation on 7 October 1949 until its reunification with West Germany on 3 October 1990. Until 1989, it was generally viewed as a communist state, and it described itself as a socialist "workers' and peasants' state".[5] The economy of this country was centrally planned and state-owned.[6] Although the GDR had to pay substantial war reparations to the Soviet Union, it became the most successful economy in the Eastern Bloc.[7][failed verification]

Before its establishment, the country's territory was administered and occupied by Soviet forces with the autonomy of the native communists following the Berlin Declaration abolishing German sovereignty in World War II; when the Potsdam Agreement established the Soviet-occupied zone, bounded on the east by the Oder–Neisse line. It was a satellite state of the Soviet Union.[8] The GDR was dominated by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), a communist party, from 1949 to 1989, before being democratized and liberalized under the impact of the Revolutions of 1989 against the communist states, helping East Germany be united with the West. Unlike West Germany, the SED did not see its state as the successor of the German Reich (1871–1945) and abolished the goal of unification in the constitution (1974). The SED-ruled GDR was often described as a Soviet satellite state; historians described it as an authoritarian regime.[9]

Geographically, the GDR bordered the Baltic Sea to the north, Poland to the east, Czechoslovakia to the southeast and West Germany to the southwest and west. Internally, the GDR also bordered the Soviet sector of Allied-occupied Berlin, known as East Berlin, which was also administered as the country's de facto capital. It also bordered the three sectors occupied by the United States, United Kingdom, and France known collectively as West Berlin (de facto part of the FRG). Emigration to the West was a significant problem as many of the emigrants were well-educated young people; such emigration weakened the state economically. In response, the GDR government fortified its inner German border and later built the Berlin Wall in 1961.[10] Many people attempting to flee[11][12][13] were killed by border guards or booby traps such as landmines.[14]

In 1989, numerous social, economic and political forces in the GDR and abroad, one of the most notable being peaceful protests starting in the city of Leipzig, led to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the establishment of a government committed to liberalization. The following year, a free and fair election was held in the country[15] and international negotiations between four occupation Allied countries and two German countries led to the signing of the Final Settlement treaty to replace the Potsdam Agreement on the status and border of future-reunited Germany. The GDR ceased to exist when its five states ("Länder") joined the Federal Republic of Germany under Article 23 of the Basic Law and its East Berlin was also united with West Berlin into a single city of the FRG, on 3 October 1990. Several of the GDR's leaders, notably its last communist leader Egon Krenz, were later prosecuted for offenses committed during the GDR's times.[16][17]

Naming conventions

The official name was Deutsche Demokratische Republik (German Democratic Republic), usually abbreviated to DDR (GDR). Both terms were used in East Germany, with increasing usage of the abbreviated form, especially since East Germany considered West Germans and West Berliners to be foreigners following the promulgation of its second constitution in 1968. West Germans, the western media and statesmen initially avoided the official name and its abbreviation, instead using terms like Ostzone (Eastern Zone),[18] Sowjetische Besatzungszone (Soviet Occupation Zone; often abbreviated to SBZ) and sogenannte DDR[19] or "so-called GDR".[20]

The centre of political power in East Berlin was – in the West – referred to as Pankow (the seat of command of the Soviet forces in Germany was in Karlshorst, a district in the East of Berlin.).[18] Over time, however, the abbreviation "DDR" was also increasingly used colloquially by West Germans and West German media.[h]

When used by West Germans, Westdeutschland (West Germany) was a term almost always in reference to the geographic region of Western Germany and not to the area within the boundaries of the Federal Republic of Germany. However, this use was not always consistent and West Berliners frequently used the term Westdeutschland to denote the Federal Republic.[21] Before World War II, Ostdeutschland (eastern Germany) was used to describe all the territories east of the Elbe (East Elbia), as reflected in the works of sociologist Max Weber and political theorist Carl Schmitt.[22][23][24][25][26]

History

Explaining the internal impact of the GDR government from the perspective of German history in the long term, historian Gerhard A. Ritter (2002) has argued that the East German state was defined by two dominant forces – Soviet communism on the one hand, and German traditions filtered through the interwar experiences of German communists on the other.[27] Throughout its existence GDR consistently grappled with the influence of the more prosperous West, against which East Germans continually measured their own nation. The notable transformations instituted by the communist regime were particularly evident in the abolition of capitalism, the overhaul of industrial and agricultural sectors, the militarization of society, and the political orientation of both the educational system and the media.

On the other hand, the new regime made relatively few changes in the historically independent domains of the sciences, the engineering professions,[28]: 185–189 the Protestant churches,[28]: 190 and in many bourgeois lifestyles.[28]: 190 Social policy, says Ritter, became a critical legitimization tool in the last decades and mixed socialist and traditional elements about equally.[28]

Origins

At the Yalta Conference during World War II, the Allies, i.e., the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), and the Soviet Union (USSR), agreed on dividing a defeated Nazi Germany into occupation zones,[29] and on dividing Berlin, the German capital, among the Allied powers as well. Initially, this meant the formation of three zones of occupation, i.e., American, British, and Soviet. Later, a French zone was carved out of the US and British zones.

1949 establishment

| Eastern Bloc |

|---|

|

The ruling communist party, known as the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), formed on 21 April 1946 from the merger between the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).[30] The two former parties were notorious rivals when they were active before the Nazis consolidated all power and criminalized them, and official East German and Soviet histories portrayed this merger as a voluntary pooling of efforts by the socialist parties and symbolic of the new friendship of German socialists after defeating their common enemy; however, there is much evidence that the merger was more troubled than commonly portrayed, and that the Soviet occupation authorities applied great pressure on the SPD's eastern branch to merge with the KPD, and the communists, who held a majority, had virtually total control over policy.[31] The SED remained the ruling party for the entire duration of the East German state. It had close ties with the Soviets, which maintained military forces in East Germany until the dissolution of the Soviet regime in 1991 (Russia continued to maintain forces in the territory of the former East Germany until 1994), with the purpose of countering NATO bases in West Germany.

As West Germany was reorganized and gained independence from its occupiers (1945–1949), the GDR was established in East Germany in October 1949. The emergence of the two sovereign states solidified the 1945 division of Germany.[32] On 10 March 1952, (in what would become known as the "Stalin Note") the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, issued a proposal to reunify Germany with a policy of neutrality, with no conditions on economic policies and with guarantees for "the rights of man and basic freedoms, including freedom of speech, press, religious persuasion, political conviction, and assembly" and free activity of democratic parties and organizations.[33] The West demurred; reunification was not then a priority for the leadership of West Germany, and the NATO powers declined the proposal, asserting that Germany should be able to join NATO and that such a negotiation with the Soviet Union would be seen as a capitulation.

In 1949 the Soviets turned control of East Germany over to the SED, headed by Wilhelm Pieck (1876–1960), who became President of the GDR and held the office until his death, while the SED general secretary Walter Ulbricht assumed most executive authority. Socialist leader Otto Grotewohl (1894–1964) became prime minister until his death.[34]

The government of East Germany denounced West German failures in accomplishing denazification and renounced ties to the Nazi past, imprisoning many former Nazis and preventing them from holding government positions. The SED set a primary goal of ridding East Germany of all traces of Nazism.[35][citation needed] It is estimated that[when?] between 180,000 and 250,000 people were sentenced to imprisonment on political grounds.[36]

Zones of occupation

In the Yalta and Potsdam conferences of 1945, the Allies established their joint military occupation and administration of Germany via the Allied Control Council (ACC), a four-power (US, UK, USSR, France) military government effective until the restoration of German sovereignty. In eastern Germany, the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ – Sowjetische Besatzungszone) comprised the five states (Länder) of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia.[37] Disagreements over the policies to be followed in the occupied zones quickly led to a breakdown in cooperation between the four powers, and the Soviets administered their zone without regard to the policies implemented in the other zones. The Soviets withdrew from the ACC in 1948; subsequently, as the other three zones were increasingly unified and granted self-government, the Soviet administration instituted a separate socialist government in its zone.[38][39]

Seven years after the Allies' 1945 Potsdam Agreement on common German policies, the USSR via the Stalin Note (10 March 1952) proposed German reunification and superpower disengagement from Central Europe, which the three Western Allies (the United States, France, the United Kingdom) rejected. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, a Communist proponent of reunification, died in early March 1953. Similarly, Lavrenty Beria, the First Deputy Prime Minister of the USSR, pursued German reunification, but he was removed from power that same year before he could act on the matter. His successor, Nikita Khrushchev, rejected reunification as equivalent to returning East Germany for annexation to the West; hence reunification was off the table until the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989.

East Germany regarded East Berlin as its capital, and the Soviet Union and the rest of the Eastern Bloc diplomatically recognized East Berlin as the capital. However, the Western Allies disputed this recognition, considering the entire city of Berlin to be occupied territory governed by the Allied Control Council. According to Margarete Feinstein, East Berlin's status as the capital was largely unrecognized by the West and by most Third World countries.[40] In practice, the ACC's authority was rendered moot by the Cold War, and East Berlin's status as occupied territory largely became a legal fiction, the Soviet sector of Berlin became fully integrated into the GDR.[41]

The deepening Cold War conflict between the Western Powers and the Soviet Union over the unresolved status of West Berlin led to the Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949). The Soviet army initiated the blockade by halting all Allied rail, road, and water traffic to and from West Berlin. The Allies countered the Soviets with the Berlin Airlift (1948–49) of food, fuel, and supplies to West Berlin.[42]

Partition

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

On 21 April 1946 the Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands – KPD) and the part of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands – SPD) in the Soviet zone merged to form the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED – Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands), which then won the elections of October 1946. The SED government nationalised infrastructure and industrial plants.

In March 1948 the German Economic Commission (Deutsche Wirtschaftskomission—DWK) under its chairman Heinrich Rau assumed administrative authority in the Soviet occupation zone, thus becoming the predecessor of an East German government.[43][44]

On 7 October 1949 the SED established the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (German Democratic Republic – GDR), based on a socialist political constitution establishing its control of the Anti-Fascist National Front of the German Democratic Republic (NF, Nationale Front der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik), an omnibus alliance of every party and mass organisation in East Germany. The NF was established to stand for election to the Volkskammer (People's Chamber), the East German parliament. The first and only president of the German Democratic Republic was Wilhelm Pieck. However, after 1950, political power in East Germany was held by the First Secretary of the SED, Walter Ulbricht.[5]

On 16 June 1953, workers constructing the new Stalinallee boulevard in East Berlin according to the GDR's officially promulgated Sixteen Principles of Urban Design, rioted against a 10% production-quota increase. Initially a labour protest, the action soon included the general populace, and on 17 June similar protests occurred throughout the GDR, with more than a million people striking in some 700 cities and towns. Fearing anti-communist counter-revolution, on 18 June 1953 the government of the GDR enlisted the Soviet Occupation Forces to aid the police in ending the riot; some fifty people were killed and 10,000 were jailed (see Uprising of 1953 in East Germany).[clarification needed][45][46]

The German war reparations owed to the Soviets impoverished the Soviet Zone of Occupation and severely weakened the East German economy. In the 1945–46 period the Soviets confiscated and transported to the USSR approximately 33% of the industrial plant and by the early 1950s had extracted some US$10 billion in reparations in agricultural and industrial products.[47] The poverty of East Germany, induced or deepened by reparations, provoked the Republikflucht ("desertion from the republic") to West Germany, further weakening the GDR's economy. Western economic opportunities induced a brain drain. In response, the GDR closed the inner German border, and on the night of 12 August 1961, East German soldiers began erecting the Berlin Wall.[48]

In 1971, Ulbricht was removed from leadership after Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev supported his ouster;[49] Erich Honecker replaced him. While the Ulbricht government had experimented with liberal reforms, the Honecker government reversed them. The new government introduced a new East German Constitution which defined the German Democratic Republic as a "republic of workers and peasants".[50]

Initially, East Germany claimed an exclusive mandate for all of Germany, a claim supported by most of the Communist bloc. It claimed that West Germany was an illegally-constituted puppet state of NATO. However, from the 1960s onward, East Germany began recognizing itself as a separate country from West Germany and shared the legacy of the united German state of 1871–1945. This was formalized in 1974 when the reunification clause was removed from the revised East German constitution. West Germany, in contrast, maintained that it was the only legitimate government of Germany. From 1949 to the early 1970s, West Germany maintained that East Germany was an illegally constituted state. It argued that the GDR was a Soviet puppet-state, and frequently referred to it as the "Soviet occupation zone". West Germany's allies shared this position until 1973. East Germany was recognized primarily by socialist countries and by the Arab bloc, along with some "scattered sympathizers".[51] According to the Hallstein Doctrine (1955), West Germany did not establish (formal) diplomatic ties with any country—except the Soviets—that recognized East German sovereignty.

In the early 1970s, the Ostpolitik ("Eastern Policy") of "Change Through Rapprochement" of the pragmatic government of FRG Chancellor Willy Brandt, established normal diplomatic relations with the East Bloc states. This policy saw the Treaty of Moscow (August 1970), the Treaty of Warsaw (December 1970), the Four Power Agreement on Berlin (September 1971), the Transit Agreement (May 1972), and the Basic Treaty (December 1972), which relinquished any separate claims to an exclusive mandate over Germany as a whole and established normal relations between the two Germanies. Both countries were admitted into the United Nations on 18 September 1973. This also increased the number of countries recognizing East Germany to 55, including the US, UK and France, though these three still refused to recognize East Berlin as the capital, and insisted on a specific provision in the UN resolution accepting the two Germanies into the UN to that effect.[51] Following the Ostpolitik, the West German view was that East Germany was a de facto government within a single German nation and a de jure state organisation of parts of Germany outside the Federal Republic. The Federal Republic continued to maintain that it could not within its own structures recognize the GDR de jure as a sovereign state under international law; but it fully acknowledged that, within the structures of international law, the GDR was an independent sovereign state. By distinction, West Germany then viewed itself as being within its own boundaries, not only the de facto and de jure government, but also the sole de jure legitimate representative of a dormant "Germany as whole".[52] The two Germanies each relinquished any claim to represent the other internationally; which they acknowledged as necessarily implying a mutual recognition of each other as both capable of representing their own populations de jure in participating in international bodies and agreements, such as the United Nations and the Helsinki Final Act.

This assessment of the Basic Treaty was confirmed in a decision of the Federal Constitutional Court in 1973;[53]

the German Democratic Republic is in the international-law sense a State and as such a subject of international law. This finding is independent of recognition in international law of the German Democratic Republic by the Federal Republic of Germany. Such recognition has not only never been formally pronounced by the Federal Republic of Germany but on the contrary repeatedly explicitly rejected. If the conduct of the Federal Republic of Germany towards the German Democratic Republic is assessed in the light of its détente policy, in particular, the conclusion of the Treaty as de facto recognition, then it can only be understood as de facto recognition of a special kind. The special feature of this Treaty is that while it is a bilateral Treaty between two States, to which the rules of international law apply and which like any other international treaty possesses validity, it is between two States that are parts of a still existing, albeit incapable of action as not being reorganized, comprehensive State of the Whole of Germany with a single body politic.[54]

Travel between the GDR and Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary became visa-free from 1972.[55]

GDR identity

From the beginning, the newly formed GDR tried to establish its own separate identity.[56] Because of the imperial and military legacy of Prussia, the SED repudiated continuity between Prussia and the GDR. The SED destroyed a number of symbolic relics of the former Prussian aristocracy: Junker manor-houses were torn down, the Berliner Stadtschloß was razed, and the equestrian statue of Frederick the Great was removed from East Berlin. Instead, the SED focused on the progressive heritage of German history, including Thomas Müntzer's role in the German Peasants' War of 1524–1525 and the role played by the heroes of the class struggle during Prussia's industrialization.

Especially after the Ninth Party Congress in 1976, East Germany upheld historical reformers such as Karl Freiherr vom Stein (1757–1831), Karl August von Hardenberg (1750–1822), Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835), and Gerhard von Scharnhorst (1755–1813) as examples and role models.[57]

East Germany was elected as a member of the UN Security Council 1980–81.

In the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, partly thanks to the U.S.-led boycott, East Germany won over a total of 126 Olympic medals, finishing second place behind the Soviet Union.

Palace of the Republic was constructed in Berlin.

Remembrance of the Third Reich

The communist regime of the GDR based its legitimacy on the struggle of anti-fascist militants. A form of resistance "cult" was established in the Buchenwald camp memorial site, with the creation of a museum in 1958, and the annual celebration of the Buchenwald oath taken on 19 April 1945 by the prisoners who pledged to fight for peace and freedom. In the 1990s, the 'state anti-fascism' of the GDR gave way to the 'state anti-communism' of the FRG. From then on, the dominant interpretation of GDR history, based on the concept of totalitarianism, led to the equivalence of communism and Nazism.[58] The historian Anne-Kathleen Tillack-Graf shows, with the help of the newspaper Neues Deutschland, how the national memorials of Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen and Ravensbrück were politically instrumentalised in the GDR, particularly during the celebrations of the liberation of the concentration camps.[59]

Although officially built in opposition to the 'fascist world' in West Germany, in 1954, 32.2% of public administration employees were former members of the Nazi Party. However, in 1961, the share of former NSDAP members among the senior administration staff was less than 10% in the GDR, compared to 67% in the FRG.[60] While in West Germany, a work of memory on the resurgence of Nazism was carried out, this was not the case in the East. Indeed, as Axel Dossmann, professor of history at the University of Jena, notes, 'this phenomenon was completely hidden. For the state-SED (the East German communist party), it was impossible to admit the existence of neo-Nazis, since the foundation of the GDR was to be an anti-fascist state. The Stasi kept an eye on them, but they were considered to be outsiders or thick-skinned bullies. These young people grew up hearing double talk. At school, it was forbidden to talk about the Third Reich and, at home, their grandparents told them how, thanks to Hitler, we had the first motorways. On 17 October 1987, thirty or so skinheads violently threw themselves into a crowd of 2,000 people at a rock concert in the Zionskirche without the police intervening.[61] In 1990, the writer Freya Klier received a death threat for writing an essay on antisemitism and xenophobia in the GDR. SPDA Vice President Wolfgang Thierse, for his part, complained in Die Welt about the rise of the extreme right in the everyday life of the inhabitants of the former GDR, in particular the terrorist group NSU, with the German journalist Odile Benyahia-Kouider explaining that "it is no coincidence that the neo-Nazi party NPD has experienced a renaissance via the East".[62]

The historian Sonia Combe observes that until the 1990s, the majority of West German historians described the Normandy landings in June 1944 as an "invasion", exonerated the Wehrmacht of its responsibility for the genocide of the Jews and fabricated the myth of a diplomatic corps that "did not know". On the contrary, Auschwitz was never a taboo in the GDR. The Nazis' crimes were the subject of extensive film, theatre and literary productions. In 1991, 16% of the population in West Germany and 6% in East Germany had antisemitic prejudices. In 1994, 40 per cent of West Germans and 22 per cent of East Germans felt that too much emphasis was placed on the genocide of the Jews.[60]

The historian Ulrich Pfeil nevertheless recalls the fact that anti-fascist commemoration in the GDR had "a hagiographic and indoctrination character".[63] As in the case of the memory of the protagonists of the German labour movement and the victims of the camps, it was "staged, censored, ordered" and, during the 40 years of the regime, was an instrument of legitimisation, repression and maintenance of power.[63]

Die Wende (German reunification)

In May 1989, following widespread public anger over the faking of results of local government elections, many GDR citizens applied for exit visas or left the country contrary to GDR laws. The impetus for this exodus of East Germans was the removal of the electrified fence along Hungary's border with Austria on 2 May 1989. Although formally the Hungarian frontier was still closed, many East Germans took the opportunity to enter Hungary via Czechoslovakia, and then make the illegal crossing from Hungary to Austria and to West Germany beyond.[64] By July, 25,000 East Germans had crossed into Hungary;[65] most of them did not attempt the risky crossing into Austria but remained instead in Hungary or claimed asylum in West German embassies in Prague or Budapest.

The opening of a border gate between Austria and Hungary at the Pan-European Picnic on 19 August 1989 then set in motion a chain reaction leading to the end of the GDR and disintegration of the Eastern Bloc. It was the largest mass escape from East Germany since the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961. The idea of opening the border at a ceremony came from Otto von Habsburg, who proposed it to Miklós Németh, then Hungarian Prime Minister, who promoted the idea.[66] The patrons of the picnic, Habsburg and Hungarian Minister of State Imre Pozsgay, who did not attend the event, saw the planned event as an opportunity to test Mikhail Gorbachev's reaction to an opening of the border on the Iron Curtain. In particular, it tested whether Moscow would give the Soviet troops stationed in Hungary the command to intervene. Extensive advertising for the planned picnic was made by the Paneuropean Union through posters and flyers among the GDR holidaymakers in Hungary. The Austrian branch of the Paneuropean Union, which was then headed by Karl von Habsburg, distributed thousands of brochures inviting GDR citizens to a picnic near the border at Sopron (near Hungary's border with Austria).[67][68][69] The local Sopron organizers knew nothing of possible GDR refugees, but envisaged a local party with Austrian and Hungarian participation.[70] But with the mass exodus at the Pan-European Picnic, the subsequent hesitant behavior of the Socialist Unity Party of East Germany and the non-intervention of the Soviet Union broke the dams. Thus the barrier of the Eastern Bloc was broken. The reaction to this from Erich Honecker in the "Daily Mirror" of 19 August 1989 was too late and showed the present loss of power: "Habsburg distributed leaflets far into Poland, on which the East German holidaymakers were invited to a picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given gifts, food and Deutsche Mark, and then they were persuaded to come to the West."[citation needed] Tens of thousands of East Germans, alerted by the media, made their way to Hungary, which was no longer ready to keep its borders completely closed or force its border troops to open fire on escapees. The GDR leadership in East Berlin did not dare to completely lock down their own country's borders.[67][69][71][72]

The next major turning point in the exodus came on 10 September 1989, when Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Horn announced that his country would no longer restrict movement from Hungary into Austria. Within two days, 22,000 East Germans crossed into Austria; tens of thousands more did so in the following weeks.[64]

Many other GDR citizens demonstrated against the ruling party, especially in the city of Leipzig. The Leipzig demonstrations became a weekly occurrence, with a turnout of 10,000 people at the first demonstration on 2 October, peaking at an estimated 300,000 by the end of the month.[73] The protests were surpassed in East Berlin, where half a million demonstrators turned out against the regime on 4 November.[73] Kurt Masur, conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, led local negotiations with the government and held town meetings in the concert hall.[74] The demonstrations eventually led Erich Honecker to resign in October; he was replaced by a slightly more moderate communist, Egon Krenz.[75]

The massive demonstration in East Berlin on 4 November coincided with Czechoslovakia formally opening its border to West Germany.[76] With the West more accessible than ever before, 30,000 East Germans made the crossing via Czechoslovakia in the first two days alone. To try to stem the outward flow of the population, the SED proposed a law loosening travel restrictions. When the Volkskammer rejected it on 5 November, the Cabinet and Politburo of the GDR resigned.[76] This left only one avenue open for Krenz and the SED: completely abolishing travel restrictions between East and West.

On 9 November 1989, a few sections of the Berlin Wall were opened, resulting in thousands of East Germans crossing freely into West Berlin and West Germany for the first time in nearly 30 years. Krenz resigned a month later, and the SED opened negotiations with the leaders of the incipient Democratic movement, Neues Forum, to schedule free elections and begin the process of democratization. As part of this process, the SED eliminated the clause in the East German constitution guaranteeing the Communists leadership of the state. The change was approved in the Volkskammer on 1 December 1989 by a vote of 420 to 0.[77]

East Germany held its last election in March 1990. The winner was Alliance for Germany, a coalition headed by the East German branch of West Germany's Christian Democratic Union, which advocated speedy reunification. Negotiations (2+4 Talks) were held involving the two German states and the former Allies, which led to agreement on the conditions for German unification. By a two-thirds vote in the Volkskammer on 23 August 1990, the German Democratic Republic declared its accession to the Federal Republic of Germany. The five original East German states that had been abolished in the 1952 redistricting were restored.[75] On 3 October 1990, the five states officially joined the Federal Republic of Germany, while East and West Berlin united as a third city-state (in the same manner as Bremen and Hamburg). On 1 July, a currency union preceded the political union: the "Ostmark" was abolished, and the Western German "Deutsche Mark" became the common currency.

Although the Volkskammer's declaration of accession to the Federal Republic had initiated the process of reunification, the act of reunification itself (with its many specific terms, conditions and qualifications, some of which involved amendments to the West German Basic Law) was achieved constitutionally by the subsequent Unification Treaty of 31 August 1990 – that is, through a binding agreement between the former Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic, now recognising each other as separate sovereign states in international law.[78] The treaty was then voted into effect prior to the agreed date for Unification by both the Volkskammer and the Bundestag by the constitutionally required two-thirds majorities, effecting on the one hand the extinction of the GDR, and on the other the agreed amendments to the Basic Law of the Federal Republic.

The great economic and socio-political inequalities between the former Germanies required government subsidies for the full integration of the German Democratic Republic into the Federal Republic of Germany. Because of the resulting deindustrialization in the former East Germany, the causes of the failure of this integration continue to be debated. Some western commentators claim that the depressed eastern economy is a natural aftereffect of a demonstrably inefficient command economy. But many East German critics contend that the shock-therapy style of privatization, the artificially high rate of exchange offered for the Ostmark, and the speed with which the entire process was implemented did not leave room for East German enterprises to adapt.[i]

Politics

There were four periods in East German political history.[79] These included: 1949–61, which saw the building of socialism; 1961–1970 after the Berlin Wall closed off escape was a period of stability and consolidation; 1971–85 was termed the Honecker Era, and saw closer ties with West Germany; and 1985–90 saw the decline and extinction of East Germany.

Organization

The ruling political party in East Germany was the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (Socialist Unity Party of Germany, SED). It was created in 1946 through the Soviet-directed merger of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in the Soviet-controlled zone. However, the SED quickly transformed into a full-fledged Communist party as the more independent-minded Social Democrats were pushed out.[57]

The Potsdam Agreement committed the Soviets to support a democratic form of government in Germany, though the Soviets' understanding of democracy was radically different from that of the West. As in other Soviet-bloc countries, non-communist political parties were allowed. Nevertheless, every political party in the GDR was forced to join the National Front of Democratic Germany, a broad coalition of parties and mass political organisations, including:

- Christlich-Demokratische Union Deutschlands (Christian Democratic Union of Germany, CDU), which merged with the West German CDU after reunification.

- Demokratische Bauernpartei Deutschlands (Democratic Farmers' Party of Germany, DBD). The party merged with the West German CDU after reunification.

- Liberal-Demokratische Partei Deutschlands (Liberal Democratic Party of Germany, LDPD), merged with the West German FDP after reunification.

- Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (National Democratic Party of Germany, NDPD), merged with the West German FDP after reunification.[57]

The member parties were almost completely subservient to the SED and had to accept its "leading role" as a condition of their existence. However, the parties did have representation in the Volkskammer and received some posts in the government.

The Volkskammer also included representatives from the mass organisations like the Free German Youth (Freie Deutsche Jugend or FDJ), or the Free German Trade Union Federation. There was also a Democratic Women's Federation of Germany, with seats in the Volkskammer.

Important non-parliamentary mass organisations in East German society included the German Gymnastics and Sports Association (Deutscher Turn- und Sportbund or DTSB), and People's Solidarity (Volkssolidarität), an organisation for the elderly. Another society of note was the Society for German-Soviet Friendship.

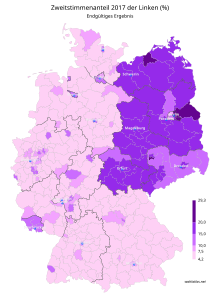

After the fall of Socialism, the SED was renamed the "Party of Democratic Socialism" (PDS) which continued for a decade after reunification before merging with the West German WASG to form the Left Party (Die Linke). The Left Party continues to be a political force in many parts of Germany, albeit drastically less powerful than the SED.[80]

State symbols

The flag of the German Democratic Republic consisted of three horizontal stripes in the traditional German-democratic colors black-red-gold with the national coat of arms of the GDR in the middle, consisting of hammer and compass, surrounded by a wreath of corn as a symbol of the alliance of workers, peasants and intelligentsia. First drafts of Fritz Behrendt's coat of arms contained only a hammer and wreath of corn, as an expression of the workers' and peasants' state. The final version was mainly based on the work of Heinz Behling.

By law of 26 September 1955, the state coat of arms with hammer, compass and wreath of corn was determined, as the state flag continues black-red-gold. By law of 1 October 1959, the coat of arms was inserted into the state flag. Until the end of the 1960s, the public display of this flag in the Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin was regarded as a violation of the constitution and public order and prevented by police measures (cf. the Declaration of the Interior Ministers of the Federation and the Länder, October 1959). It was not until 1969 that the Federal Government decreed "that the police should no longer intervene anywhere against the use of the flag and coat of arms of the GDR."

At the request of the DSU, the first freely elected People's Chamber of the GDR decided on 31 May 1990 that the GDR state coat of arms should be removed within a week in and on public buildings. Nevertheless, until the official end of the republic, it continued to be used in a variety of ways, for example on documents.

The text Resurrected from Ruins of the National Anthem of the GDR is by Johannes R. Becher, the melody by Hanns Eisler. From the beginning of the 1970s to the end of 1989, however, the text of the anthem was no longer sung due to the passage "Deutschland einig Vaterland".

-

Provisional coat of arms of the GDR

(12 January 1950 to 28 May 1953) -

Provisional coat of arms of the GDR

(28 May 1953 to 26 September 1955) -

Coat of arms of the GDR

(26 September 1955 to 2 October 1990) -

Flag of the GDR

(7 October 1949 to 1 October 1959) -

Commercial flag

(1959–1973) -

Flag of the GDR

(1 October 1959 to 3 October 1990)

Presidential standard

The first standard of the president had the shape of a rectangular flag in the colors black-red-gold with the inscription "President" in yellow in the red stripe, as well as "D.D.R." (contrary to the official abbreviation with dots) in the stripe below in black letters. The flag was surrounded by a stripe of yellow color. An original of the standard is in the German Historical Museum in Berlin.

-

Presidential standard 1951–1953

(The emblem was already introduced on 12 January 1950, the standard was adopted on 29 January 1951.) -

Presidential standard 1953–1955

(The emblem of the GDR was changed on 28 May 1953 and already resembled the final coat of arms of 1955.) -

Standard of the president 1955–1960

(The standard was maintained until 7 September 1960, when Wilhelm Pieck died and the presidency was abolished.) -

Standard of the chairman of the Council of State 1960–1990

War and Service Flags and Symbols

The flags of the military units of the GDR bore the national coat of arms with a wreath of two olive branches on a red background in the black-red-gold flag.

The flags of the People's Navy for combat ships and boats bore the coat of arms with olive branch wreath on red, for auxiliary ships and boats on blue flag cloth with a narrow and centrally arranged black-red-gold band. As Gösch, the state flag was used in a reduced form.

The ships and boats of the Border Brigade Coast on the Baltic Sea and the boats of the border troops of the GDR on the Elbe and Oder carried a green bar on the Liekjust like the service flag of the border troops.

-

Service flag of the National People's Army

-

Service flag for combat ships and boats of the People's Navy

-

Service flag for auxiliary ships and boats of the People's Navy

-

Deutsche Post (1955–1973)

-

Service flag for ships and boats of the Border Brigade Coast

-

Service flag of the border troops

-

Flag of the Ministry of State Security (Stasi), East Germany, until 1990

-

Emblem of the Ministry of State Security (MfS) (Stasi) of the GDR (until 1990)

-

Coat of arms of National People's Army of the German Democratic Republic (from 1956 until 1990)

-

Emblem of the Ground Forces of National People's Army (1956–1990)

-

The coat of arms of the People's Navy with the Order of Karl Marx (between 1956 and 1990)

-

Emblem of Air Force of the National People's Army of the German Democratic Republic before 1959 (until 1956 the People's Police Air of the GDR)

-

Emblem of aircraft of National People's Army of the German Democratic Republic (1959–1990)

-

Emblem of the Grenztruppen used for vehicles (1949–1990)

-

The national ensign of the GDR Volkspolizei-Bereitschaften (from 1962 to 1990)

-

Combat Groups of the Working Class coat of arms of the fighting groups of the working class, without oak leaves (between 1953 and 1990)

-

Logo of the Organization of the Warsaw Pact (14 May 1955)

Political and social emblems

After being a member of the Thälmann Pioneers, which was for schoolchildren ages 6 to 14, East German youths would usually join the FDJ.

-

Emblem of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (1950–1990)

-

Flag of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (1950–1990)

-

Emblem of the Free German Youth

-

Flag of the Free German Youth

-

Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation Emblem (13 December 1948 – August 1990)

-

Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation Flag (13 December 1948 – August 1990)

Young Pioneer programs

Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation

Young Pioneers and the Thälmann Pioneers, was a youth organisation of schoolchildren aged 6 to 14 in East Germany.[81] They were named after Ernst Thälmann, the former leader of the Communist Party of Germany, who was executed at the Buchenwald concentration camp.[82]

The group was a subdivision of the Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ, Free German Youth), East Germany's youth movement.[83] It was founded on 13 December 1948 and broke apart in 1989 on German reunification.[84] In the 1960s and 1970s, nearly all schoolchildren between ages 6 and 14 were organised into Young Pioneer or Thälmann Pioneer groups, with the organisations having "nearly two million children" collectively by 1975.[84]

The pioneer group was loosely based on Scouting, but organised in such a way as to teach schoolchildren aged 6 – 14 socialist ideology and prepare them for the Freie Deutsche Jugend, the FDJ.[84]

The program was designed to follow the Soviet Pioneer program Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization. The pioneers' slogan was Für Frieden und Sozialismus seid bereit – Immer bereit" ("For peace and socialism be ready – always ready"). This was usually shortened to "Be ready – always ready". This was recited at the raising of the flag. One person said the first part, "Be ready!": this was usually the pioneer leader, the teacher or the head of the local pioneer group. The pioneers all answered "Always ready", stiffening their right hand and placing it against their forehead with the thumb closest and their little finger facing skywards.[84]

Both Pioneer groups would often have massive parades, honoring and celebrating the Socialist success of their nations.

Membership

Membership in the Young Pioneers and the Thälmann Pioneers was formally voluntary. On the other hand, it was taken for granted by the state and thus by the school as well as by many parents. In practice, the initiative for the admission of all students in a class came from the school. As the membership quota of up to 98 percent of the students (in the later years of the GDR) shows, the six- or ten-year-olds (or their parents) had to become active on their own in order not to become members. Nevertheless, there were also children who did not become members. Rarely, students were not admitted because of poor academic performance or bad behavior "as a punishment" or excluded from further membership.

Uniform

The pioneers' uniform consisted of white shirts and blouses bought by their parents, along with blue trousers or skirts until the 1970s and on special occasions. But often the only thing worn was the most important sign of the future socialist – the triangular necktie. At first this was blue, but from 1973, the Thälmann pioneers wore a red necktie like the pioneers in the Soviet Union, while the Young Pioneers kept the blue one. Pioneers wore their uniforms at political events and state holidays such as the workers' demonstrations on May Day, as well as at school festivals and pioneer events.[84]

The pioneer clothing consisted of white blouses and shirts that could be purchased in sporting goods stores. On the left sleeve there was a patch with the embroidered emblem of the pioneer organization and, if necessary, a rank badge with stripes in the color of the scarf. These rank badges were three stripes for Friendship Council Chairmen, two stripes for Group Council Chairmen and Friendship Council members, one stripe for all other Group Council members. In some cases, symbols for special functions were also sewn on at this point, for example a red cross for a boy paramedic. Dark blue trousers or skirts were worn and a dark blue cap with the pioneer emblem served as a cockadeas a headgear. At the beginning of the 1970s, a windbreaker/blouson and a dark red leisure blouse were added.

However, the pioneer clothing was only worn completely on special occasions, such as flag appeals, commemoration days or festive school events, but it was usually not prescribed.

From the 1960s, the requirement of trousers/skirt was dispensed with in many places, and the dress code was also relaxed with regard to the cap. For pioneer afternoons or other activities, often only the triangular scarf was worn. In contrast to the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries, a blue scarf was common in the GDR. It was not until 1973, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the organization, that the red scarf was introduced for the Thälmann pioneers, while the young pioneers remained with the blue scarf. The change of color of the scarf was solemnly designed in the pioneer organization.

From 1988 there was an extended clothing range, consisting of a Nicki in the colors white, light yellow, turquoise or pink (with an imprint of the symbol of the pioneer organization), long and short trousers with a snap belt and, for the colder months, a lined windbreaker in red for girls and gray for boys.

Suitable pioneers were trained as paramedics; after their training, they wore the badge "Young Paramedic".

Music

The Pioneer songs were sung at any opportunity, including the following titles:

- "Wir tragen die Blaue Fahne" – "We Carry the Blue Flag"

- "Unser kleiner Trompeter" – "Our Little Trumpeter"

- "Thälmann-Lied" – "Thälmann Song"

- "Pioniermarsch" – "Pioneers' March"

- "Der Volkspolizist" – " The People's Policeman"

- "Jetzt bin ich Junger Pionier" – "Now I Am a Young Pioneer"

- "Unsere Heimat" – "Our Heimat"

- "Die Heimat hat sich schön gemacht" – "Our Homeland Has Smartened Itself Up"

- "Auf zum Sozialismus" – "Onwards to Socialism"

- "Kleine weiße Friedenstaube" – "Little White Dove of Peace"

- "Lied der jungen Naturforscher" – "Song of the Young Nature Researchers"

- "Wenn Mutti früh zur Arbeit geht" – "When Mother Goes to Work in the Morning"

- "Gute Freunde" – "Good Friends"

- "Hab'n Se nicht noch Altpapier" – "Got Any Waste Paper?"

- "Pioniere voran!" – "Onwards, Pioneers!"

- "Laßt Euch grüßen, Pioniere" – "Greetings, Pioneers"

- "Immer lebe die Sonne" – "May There Always Be Sunshine"

- "Friede auf unserer Erde" – "Peace on Our Earth"

Free German Youth

Freie Deutsche Jugend, organization was meant for young people, both male and female, between the ages of 14 and 25 and comprised about 75% of the young population of former East Germany.[86] In 1981–1982, this meant 2.3 million members.[87] After being a member of the Thälmann Pioneers, which was for schoolchildren ages 6 to 14, East German youths would usually join the FDJ.[88]

The FDJ increasingly developed into an instrument of communist rule and became a member of the 'democratic bloc' in 1950.[85] However, the FDJ's focus of 'happy youth life', which had characterised the 1940s, was increasingly marginalised following Walter Ulbricht's emphasis of the 'accelerated construction of socialism' at the 4th Parliament and a radicalisation of SED policy in July 1952.[89] In turn, a more severe anti-religious agenda, whose aim was to obstruct the Church youths' work, grew within the FDJ, ultimately reaching a high point in mid-April 1953 when the FDJ newspaper Junge Welt reported on details of the 'criminal' activities of the 'illegal' Junge Gemeinden FDJ gangs were sent to church meetings to heckle those inside and school tribunals interrogated or expelled students who refused to join the FDJ for religious reasons.[90]

Membership

Upon request, the young people were admitted to the FDJ from the age of 14. Membership was voluntary according to the statutes, but non-members had to fear considerable disadvantages in admission to secondary schools as well as in the choice of studies and careers and were also exposed to strong pressure from line-loyal teachers to join the organization. By the end of 1949, around one million young people had joined it, which corresponded to almost a third of the young people. Only in Berlin, where other youth organizations were also admitted due to the four-power status, the proportion of FDJ members in youth was limited to just under 5 percent in 1949. [6] In 1985, the organization had about 2.3 million members, corresponding to about 80 percent of all GDR youths between the ages of 14 and 25. Most young people tacitly ended their FDJ membership after completing their apprenticeship or studies when they entered the workforce. However, during the period of military service in the NVA, those responsible (political officer, FDJ secretary) attached great importance to reviving FDJ membership. The degree of organisation was much higher in urban areas than in rural areas.

The FDJ clothing was the blue FDJ shirt ("blue shirt")– for girls the blue FDJ blouse – with the FDJ emblem of the rising sun on the left sleeve. The greeting of the FDJers was "friendship". Until the end of the GDR, the income-dependent membership fee was between 0.30 and 5.00 marks per month.

Music

The Festival of Political Songs (Template:Lang-de) was one of the largest music events in East Germany, held between 1970 and 1990. It was hosted by the Free German Youth and featured international artists.

Uniform

The blue shirt (also: FDJ shirt or FDJ blouse) was since 1948 the official organizational clothing of the GDR youth organization Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ). On official occasions, FDJ members had to wear their blue shirts. The FDJ shirt – an FDJ blouse for girls – was a long-sleeved shirt of blue color with a folding collar, epaulettes and chest pockets. On the left sleeve was the FDJ symbol of the rising sun sewn up. Until the 1970s, the blue shirts were only made of cotton, later there was a cheaper variant made of polyester mixture.

The epaulettes of the blue shirt, in contrast to epaulettes on military uniforms, did not serve to make visible rank or unit membership, but were used at most to put a beret through. Official functions in the FDJ, for example FDJ secretary of a school or apprentice class, had no rank badges and could not be read on the FDJ shirt. However, the members of the FDJ order groups officially wore the FDJ shirt together with a red armband during their missions.

From the 1970s onwards, official patches and pins were issued for certain events, which could be worn on the FDJ shirt. There was no fixed wearing style. The orders and decorations that ordinary FDJ members received until the end of their membership at the age of 19 to 24 – usually the badge of good knowledge – were usually not worn. As a rule, only full-time FDJ members on the way to the nomenklatura at an older age achieved awards, which were also worn.

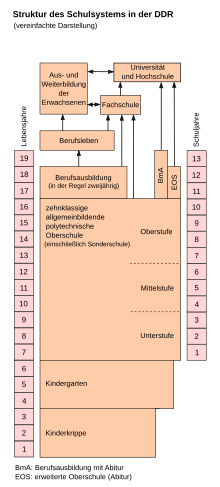

Education and social care

About 600,000 children and youth were subordinate to East German residential child care system.

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 18,388,000 | — |

| 1960 | 17,188,000 | −6.5% |

| 1970 | 17,068,000 | −0.7% |

| 1980 | 16,740,000 | −1.9% |

| 1990 | 16,028,000 | −4.3% |

| Source: DESTATIS | ||

The East German population declined by three million people throughout its forty-one year history, from 19 million in 1948 to 16 million in 1990; of the 1948 population, some four million were deported from the lands east of the Oder-Neisse line, which made the home of millions of Germans part of Poland and the Soviet Union.[91] This was a stark contrast from Poland, which increased during that time; from 24 million in 1950 (a little more than East Germany) to 38 million (more than twice of East Germany's population). This was primarily a result of emigration—about one quarter of East Germans left the country before the Berlin Wall was completed in 1961,[92] and after that time, East Germany had very low birth rates,[93] except for a recovery in the 1980s when the birth rate in East Germany was considerably higher than in West Germany.[94]

Vital statistics

| Average population (thousand)[95] | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1,000) | Crude death rate (per 1,000) | Natural change (per 1,000) | Total fertility rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | 188,679 | 413,240 | −224,561 | 10.2 | 22.4 | −12.1 | 1.30 | |

| 1947 | 247,275 | 358,035 | −110,760 | 13.1 | 19.0 | −5.9 | 1.75 | |

| 1948 | 243,311 | 289,747 | −46,436 | 12.7 | 15.2 | −2.4 | 1.76 | |

| 1949 | 274,022 | 253,658 | 20,364 | 14.5 | 13.4 | 1.1 | 2.03 | |

| 1950 | 18,388 | 303,866 | 219,582 | 84,284 | 16.5 | 11.9 | 4.6 | 2.35 |

| 1951 | 18,350 | 310,772 | 208,800 | 101,972 | 16.9 | 11.4 | 5.6 | 2.46 |

| 1952 | 18,300 | 306,004 | 221,676 | 84,328 | 16.6 | 12.1 | 4.6 | 2.42 |

| 1953 | 18,112 | 298,933 | 212,627 | 86,306 | 16.4 | 11.7 | 4.7 | 2.40 |

| 1954 | 18,002 | 293,715 | 219,832 | 73,883 | 16.3 | 12.2 | 4.1 | 2.38 |

| 1955 | 17,832 | 293,280 | 214,066 | 79,215 | 16.3 | 11.9 | 4.4 | 2.38 |

| 1956 | 17,604 | 281,282 | 212,698 | 68,584 | 15.8 | 12.0 | 3.9 | 2.30 |

| 1957 | 17,411 | 273,327 | 225,179 | 48,148 | 15.6 | 12.9 | 2.7 | 2.24 |

| 1958 | 17,312 | 271,405 | 221,113 | 50,292 | 15.6 | 12.7 | 2.9 | 2.22 |

| 1959 | 17,286 | 291,980 | 229,898 | 62,082 | 16.9 | 13.3 | 3.6 | 2.37 |

| 1960 | 17,188 | 292,985 | 233,759 | 59,226 | 16.9 | 13.5 | 3.4 | 2.35 |

| 1961 | 17,079 | 300,818 | 222,739 | 78,079 | 17.6 | 13.0 | 4.6 | 2.42 |

| 1962 | 17,136 | 297,982 | 233,995 | 63,987 | 17.4 | 13.7 | 3.7 | 2.42 |

| 1963 | 17,181 | 301,472 | 222,001 | 79,471 | 17.6 | 12.9 | 4.6 | 2.47 |

| 1964 | 17,004 | 291,867 | 226,191 | 65,676 | 17.1 | 13.3 | 3.9 | 2.48 |

| 1965 | 17,040 | 281,058 | 230,254 | 50,804 | 16.5 | 13.5 | 3.0 | 2.48 |

| 1966 | 17,071 | 267,958 | 225,663 | 42,295 | 15.7 | 13.2 | 2.5 | 2.43 |

| 1967 | 17,090 | 252,817 | 227,068 | 25,749 | 14.8 | 13.3 | 1.5 | 2.34 |

| 1968 | 17,087 | 245,143 | 242,473 | 2,670 | 14.3 | 14.2 | 0.1 | 2.30 |

| 1969 | 17,075 | 238,910 | 243,732 | −4,822 | 14.0 | 14.3 | −0.3 | 2.24 |

| 1970 | 17,068 | 236,929 | 240,821 | −3,892 | 13.9 | 14.1 | −0.2 | 2.19 |

| 1971 | 17,054 | 234,870 | 234,953 | −83 | 13.8 | 13.8 | −0.0 | 2.13 |

| 1972 | 17,011 | 200,443 | 234,425 | −33,982 | 11.7 | 13.7 | −2.0 | 1.79 |

| 1973 | 16,951 | 180,336 | 231,960 | −51,624 | 10.6 | 13.7 | −3.0 | 1.58 |

| 1974 | 16,891 | 179,127 | 229,062 | −49,935 | 10.6 | 13.5 | −3.0 | 1.54 |

| 1975 | 16,820 | 181,798 | 240,389 | −58,591 | 10.8 | 14.3 | −3.5 | 1.54 |

| 1976 | 16,767 | 195,483 | 233,733 | −38,250 | 11.6 | 13.9 | −2.3 | 1.64 |

| 1977 | 16,758 | 223,152 | 226,233 | −3,081 | 13.3 | 13.5 | −0.2 | 1.85 |

| 1978 | 16,751 | 232,151 | 232,332 | −181 | 13.9 | 13.9 | −0.0 | 1.90 |

| 1979 | 16,740 | 235,233 | 232,742 | 2,491 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 0.1 | 1.90 |

| 1980 | 16,740 | 245,132 | 238,254 | 6,878 | 14.6 | 14.2 | 0.4 | 1.94 |

| 1981 | 16,706 | 237,543 | 232,244 | 5,299 | 14.2 | 13.9 | 0.3 | 1.85 |

| 1982 | 16,702 | 240,102 | 227,975 | 12,127 | 14.4 | 13.7 | 0.7 | 1.86 |

| 1983 | 16,701 | 233,756 | 222,695 | 11,061 | 14.0 | 13.3 | 0.7 | 1.79 |

| 1984 | 16,660 | 228,135 | 221,181 | 6,954 | 13.6 | 13.2 | 0.4 | 1.74 |

| 1985 | 16,640 | 227,648 | 225,353 | 2,295 | 13.7 | 13.5 | 0.2 | 1.73 |

| 1986 | 16,640 | 222,269 | 223,536 | −1,267 | 13.4 | 13.5 | −0.1 | 1.70 |

| 1987 | 16,661 | 225,959 | 213,872 | 12,087 | 13.6 | 12.8 | 0.8 | 1.74 |

| 1988 | 16,675 | 215,734 | 213,111 | 2,623 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 0.1 | 1.67 |

| 1989 | 16,434 | 198,992 | 205,711 | −6,789 | 12.0 | 12.4 | −0.4 | 1.56 |

| 1990 | 16,028 | 178,476 | 208,110 | −29,634 | 11.1 | 12.9 | −1.8 | 1.51 |

| Source:[96] | ||||||||

Major cities

(1988 populations)

- East Berlin (1,200,000)

- Leipzig[97] (556,000)

- Dresden[98] (520,000)

- Karl-Marx-Stadt[99] (314,437) (Chemnitz until 1953, reverted to original name in 1990)

- Magdeburg[99] (290,579)

- Rostock[99] (253,990)

- Halle (Saale)[99] (236,044)

- Erfurt[99] (220,016)

- Potsdam[99] (142,862)

- Gera[99] (134,834)

- Schwerin[99] (130,685)

- Cottbus[99] (128,639)

- Zwickau[99] (121,749)

- Jena[99] (108,010)

- Dessau[99] (103,867)

Administrative districts

Until 1952, East Germany comprised the capital, East Berlin (though legally it was not fully part of the GDR's territory), and the five German states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in 1947 renamed Mecklenburg), Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt (named Province of Saxony until 1946), Thuringia, and Saxony, their post-war territorial demarcations approximating the pre-war German demarcations of the Middle German Länder (states) and Provinzen (provinces of Prussia). The western parts of two provinces, Pomerania and Lower Silesia, the remainder of which were annexed by Poland, remained in the GDR and were attached to Mecklenburg and Saxony, respectively.

The East German Administrative Reform of 1952 established 14 Bezirke (districts) and de facto disestablished the five Länder. The new Bezirke, named after their district centres, were as follows: (i) Rostock, (ii) Neubrandenburg, and (iii) Schwerin created from the Land (state) of Mecklenburg; (iv) Potsdam, (v) Frankfurt (Oder), and (vii) Cottbus from Brandenburg; (vi) Magdeburg and (viii) Halle from Saxony-Anhalt; (ix) Leipzig, (xi) Dresden, and (xii) Karl-Marx-Stadt (Chemnitz until 1953 and again from 1990) from Saxony; and (x) Erfurt, (xiii) Gera, and (xiv) Suhl from Thuringia.

East Berlin was made the country's 15th Bezirk in 1961 but retained special legal status until 1968, when the residents approved the new (draft) constitution. Despite the city as a whole being legally under the control of the Allied Control Council, and diplomatic objections of the Allied governments, the GDR administered the Bezirk of Berlin as part of its territory.

Military

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

The government of East Germany had control over a large number of military and paramilitary organisations through various ministries. Chief among these was the Ministry of National Defence. Because of East Germany's proximity to the West during the Cold War (1945–92), its military forces were among the most advanced of the Warsaw Pact. Defining what was a military force and what was not is a matter of some dispute.

National People's Army

The Nationale Volksarmee (NVA) was the largest military organisation in East Germany. It was formed in 1956 from the Kasernierte Volkspolizei (Barracked People's Police), the military units of the regular police (Volkspolizei), when East Germany joined the Warsaw Pact. From its creation, it was controlled by the Ministry of National Defence (East Germany). It was an all-volunteer force until an eighteen-month conscription period was introduced in 1962.[100][101] It was regarded by NATO officers as the best military in the Warsaw Pact.[102] The NVA consisted of the following branches:

- Land Forces of the National People's Army

- Volksmarine – People's Navy

- Air Forces of the National People's Army

Border troops

The border troops of the Eastern sector were originally organised as a police force, the Deutsche Grenzpolizei, similar to the Bundesgrenzschutz in West Germany. It was controlled by the Ministry of the Interior. Following the remilitarisation of East Germany in 1956, the Deutsche Grenzpolizei was transformed into a military force in 1961, modeled after the Soviet Border Troops, and transferred to the Ministry of National Defense, as part of the National People's Army. In 1973, it was separated from the NVA, but it remained under the same ministry. At its peak, it numbered approximately 47,000 men.

Volkspolizei-Bereitschaft

After the NVA was separated from the Volkspolizei in 1956, the Ministry of the Interior maintained its own public order barracked reserve, known as the Volkspolizei-Bereitschaften (VPB). These units were, like the Kasernierte Volkspolizei, equipped as motorised infantry, and they numbered between 12,000 and 15,000 men.

Stasi

The Ministry of State Security (Stasi) included the Felix Dzerzhinsky Guards Regiment, which was mainly involved with facilities security and plain clothes events security. They were the only public facing wing of the Stasi. The Stasi numbered around 90,000 men, the Guards Regiment around 11,000–12,000 men.[citation needed]

Combat groups of the working class

The Kampfgruppen der Arbeiterklasse (combat groups of the working class) numbered around 400,000 for much of their existence, and were organised around factories. The KdA was the political-military instrument of the SED; it was essentially a "party Army". All KdA directives and decisions were made by the ZK's Politbüro. They received their training from the Volkspolizei and the Ministry of the Interior. Membership was voluntary, but SED members were required to join as part of their membership obligation.

Conscientious objection

Every man was required to serve eighteen months of compulsory military service; for the medically unqualified and conscientious objector, there were the Baueinheiten (construction units) or the Volkshygienedienst (people's sanitation service) both established in 1964, two years after the introduction of conscription, in response to political pressure by the national Lutheran Protestant Church upon the GDR's government. In the 1970s, East German leaders acknowledged that former construction soldiers and sanitation service soldiers were at a disadvantage when they rejoined the civilian sphere.[citation needed]

Foreign policy

Support of Third World socialist countries

After receiving wider international diplomatic recognition in 1972–73, the GDR began active cooperation with Third World socialist governments and national liberation movements. While the USSR was in control of the overall strategy and Cuban armed forces were involved in the actual combat (mostly in the People's Republic of Angola and socialist Ethiopia), the GDR provided experts for military hardware maintenance and personnel training, and oversaw creation of secret security agencies based on its own Stasi model.

Already in the 1960s, contacts were established with Angola's MPLA, Mozambique's FRELIMO and the PAIGC in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde. In the 1970s official cooperation was established with other socialist states, such as the People's Republic of the Congo, People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, Somali Democratic Republic, Libya, and the People's Republic of Benin.

The first military agreement was signed in 1973 with the People's Republic of the Congo. In 1979 friendship treaties were signed with Angola, Mozambique and Ethiopia.

It was estimated that altogether, 2,000–4,000 DDR military and security experts were dispatched to Africa. In addition, representatives from African and Arab countries and liberation movements underwent military training in the GDR.[103]

East Germany and the Middle East conflict

East Germany pursued an anti-Zionist policy; Jeffrey Herf argues that East Germany was waging an undeclared war on Israel.[104] According to Herf, "the Middle East was one of the crucial battlefields of the global Cold War between the Soviet Union and the West; it was also a region in which East Germany played a salient role in the Soviet bloc's antagonism toward Israel."[105] While East Germany saw itself as an "anti-fascist state", it regarded Israel as a "fascist state"[106] and East Germany strongly supported the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in its armed struggle against Israel. In 1974, the GDR government recognized the PLO as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people".[107] The PLO declared the Palestinian state on 15 November 1988 during the First Intifada, and the GDR recognized the state prior to reunification.[108] After becoming a member of the UN, East Germany "made excellent use of the UN to wage political warfare against Israel [and was] an enthusiastic, high-profile, and vigorous member" of the anti-Israeli majority of the General Assembly.[104]

Ba'athist Iraq, due to its wealth of unexploited natural resources, was sought out as an ally of East Germany, with Iraq being the first Arab country to recognise East Germany on 10 May 1969, paving the way for other Arab League states to later do the same. East Germany attempted to play a decisive role in mediating the conflict between the Iraqi Communist Party and the Ba'ath Party and supported the creation of the National Progressive Front. The East German government also attempted to foster close relations with the Ba'athist regime of Hafez al-Assad during the early years of Assad's regime and, as it did in Iraq, used its influence to minimise tensions between the Syrian Communist Party and the Ba'athist regime.[109]

Western Europe

During the Cold War, especially during its early years, the East German government attempted to build closer diplomatic relations and trade links between Iceland and East Germany. By the 1950s, East Germany had become Iceland's fifth largest trading partner. East German influence in Iceland significantly declined in the 1970s and 1980s following a schism between the Socialist Unity Party of Germany and the Icelandic Socialist Party over the Prague Spring, along with free market economic reforms implemented by Iceland during the 1960s.[110]

Soviet military occupation

Economy

The East German economy began poorly because of the devastation caused by the Second World War; the loss of so many young soldiers, the disruption of business and transportation, the allied bombing campaigns that decimated cities, and reparations owed to the USSR. The Red Army dismantled and transported to Russia the infrastructure and industrial plants of the Soviet Zone of Occupation. By the early 1950s, the reparations were paid in agricultural and industrial products; and Lower Silesia, with its coal mines and Szczecin, an important natural port, were given to Poland by the decision of Stalin and in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement.[47]

The socialist centrally planned economy of the German Democratic Republic was like that of the USSR. In 1950, the GDR joined the COMECON trade bloc. In 1985, collective (state) enterprises earned 96.7% of the net national income. To ensure stable prices for goods and services, the state paid 80% of basic supply costs. The estimated 1984 per capita income was $9,800 ($22,600 in 2015 dollars) (this is based on an unreal official exchange rate). In 1976, the average annual growth of the GDP was approximately five percent. This made the East German economy the richest in all of the Soviet Bloc until reunification in 1990.[7]

Notable East German exports were photographic cameras, under the Praktica brand; automobiles under the Trabant, Wartburg, and the IFA brands; hunting rifles, sextants, typewriters and wristwatches.

Until the 1960s, East Germans endured shortages of basic foodstuffs such as sugar and coffee. East Germans with friends or relatives in the West (or with any access to a hard currency) and the necessary Staatsbank foreign currency account could afford Western products and export-quality East German products via Intershop. Consumer goods also were available, by post, from the Danish Jauerfood, and Genex companies.

The government used money and prices as political devices, providing highly subsidised prices for a wide range of basic goods and services, in what was known as "the second pay packet".[111] At the production level, artificial prices made for a system of semi-barter and resource hoarding. For the consumer, it led to the substitution of GDR money with time, barter, and hard currencies. The socialist economy became steadily more dependent on financial infusions from hard-currency loans from West Germany. East Germans, meanwhile, came to see their soft currency as worthless relative to the Deutsche Mark (DM).[112] Economic issues would also persist in the east of Germany after the reunification of the west and the east. According to the federal office of political education (23 June 2009) 'In 1991 alone, 153 billion Deutschmarks had to be transferred to eastern Germany to secure incomes, support businesses and improve infrastructure... by 1999 the total had amounted to 1.634 trillion Marks net... The sums were so large that public debt in Germany more than doubled.'[113]

Consumption and jobs

| East Germany | West Germany | |

| 1945–1960 | 6.2 | 10.9 |

| 1950–1960 | 6.7 | 8.0 |

| 1960–1970 | 2.7 | 4.4 |

| 1970–1980 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| 1980–1989 | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| Total 1950–1989 | 3.1 | 4.3 |

Loyalty to the SED was a primary criterion for getting a good job, professionalism was secondary to political criteria in personnel recruitment and development.[115]

Beginning in 1963 with a series of secret international agreements, East Germany recruited workers from Poland, Hungary, Cuba, Albania, Mozambique, Angola and North Vietnam. They numbered more than 100,000 by 1989. Many, such as future politician Zeca Schall (who emigrated from Angola in 1988 as a contract worker) stayed in Germany after the Wende.[116]

Religion

Religion became contested ground in the GDR, with the governing communists promoting state atheism, although some people remained loyal to Christian communities.[117] In 1957, the state authorities established a State Secretariat for Church Affairs to handle the government's contact with churches and with religious groups;[118] the SED remained officially atheist.[119]

In 1950, 85% of the GDR citizens were Protestants, while 10% were Catholics. In 1961, the renowned philosophical theologian Paul Tillich claimed that the Protestant population in East Germany had the most admirable Church in Protestantism, because the communists there had not been able to win a spiritual victory over them.[120] By 1989, membership in the Christian churches had dropped significantly. Protestants constituted 25% of the population, Catholics 5%. The share of people who considered themselves non-religious rose from 5% in 1950 to 70% in 1989.

State atheism

When it first came to power, the Communist party asserted the compatibility of Christianity and Marxism-Leninism and sought Christian participation in the building of socialism. At first, the promotion of Marxist-Leninist atheism received little official attention. In the mid-1950s, as the Cold War heated up, atheism became a topic of major interest for the state, in both domestic and foreign contexts. University chairs and departments devoted to the study of scientific atheism were founded and much literature (scholarly and popular) on the subject was produced. This activity subsided in the late 1960s amid perceptions that it had started to become counterproductive. Official and scholarly attention to atheism renewed beginning in 1973, though this time with more emphasis on scholarship and on the training of cadres than on propaganda. Throughout, the attention paid to atheism in East Germany was never intended to jeopardise the cooperation that was desired from those East Germans who were religious.[121]

Protestantism

East Germany, historically, was majority Protestant (primarily Lutheran) from the early stages of the Protestant Reformation onwards. In 1948, freed from the influence of the Nazi-oriented German Christians, Lutheran, Reformed and United churches from most parts of Germany came together as the Protestant Church in Germany (Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland, EKD) at the Conference of Eisenach (Kirchenversammlung von Eisenach).

In 1969, the regional Protestant churches in East Germany and East Berlin[j] broke away from the EKD and formed the Federation of Protestant Churches in the German Democratic Republic (Template:Lang-de, BEK), in 1970 also joined by the Moravian Herrnhuter Brüdergemeinde. In June 1991, following the German reunification, the BEK churches again merged with the EKD ones.

Between 1956 and 1971, the leadership of the East German Lutheran churches gradually changed its relations with the state from hostility to cooperation.[122] From the founding of the GDR in 1949, the Socialist Unity Party sought to weaken the influence of the church on the rising generation. The church adopted an attitude of confrontation and distance toward the state. Around 1956 this began to develop into a more neutral stance accommodating conditional loyalty. The government was no longer regarded as illegitimate; instead, the church leaders started viewing the authorities as installed by God and, therefore, deserving of obedience by Christians. But on matters where the state demanded something which the churches felt was not in accordance with the will of God, the churches reserved their right to say no. There were both structural and intentional causes behind this development. Structural causes included the hardening of Cold War tensions in Europe in the mid-1950s, which made it clear that the East German state was not temporary. The loss of church members also made it clear to the leaders of the church that they had to come into some kind of dialogue with the state. The intentions behind the change of attitude varied from a traditional liberal Lutheran acceptance of secular power to a positive attitude toward socialist ideas.[123]