John McCain

John McCain | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

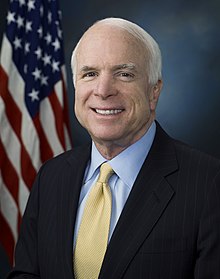

Official portrait, 2009 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United States Senator from Arizona | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office January 3, 1987 – August 25, 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Barry Goldwater | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jon Kyl | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona's 1st district | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office January 3, 1983 – January 3, 1987 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | John Jacob Rhodes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | John Jacob Rhodes III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | John Sidney McCain III August 29, 1936 Coco Solo, Panama Canal Zone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | August 25, 2018 (aged 81) Cornville, Arizona, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | United States Naval Academy Cemetery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Republican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 7, including Meghan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Joe McCain (brother) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | United States Naval Academy (BS) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Civilian awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (posthumous, 2022) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | Senate website | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | John Wayne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | United States Navy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1958–1981 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Captain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military awards |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American statesman[2] and naval officer who represented the state of Arizona in Congress for over 35 years, first as a Representative from 1983 to 1987, and then as a U.S. senator from 1987 until his death in 2018. He was the Republican Party's nominee in the 2008 U.S. presidential election.

McCain was a son of Admiral John S. McCain Jr. and grandson of Admiral John S. McCain Sr. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1958 and received a commission in the U.S. Navy. McCain became a naval aviator and flew ground-attack aircraft from aircraft carriers. During the Vietnam War, he almost died in the 1967 USS Forrestal fire. While on a bombing mission during Operation Rolling Thunder over Hanoi in October 1967, McCain was shot down, seriously injured, and captured by the North Vietnamese. He was a prisoner of war until 1973. McCain experienced episodes of torture and refused an out-of-sequence early release. He sustained wounds that left him with lifelong physical disabilities. McCain retired from the Navy as a captain in 1981 and moved to Arizona.

In 1982, McCain was elected to the House of Representatives, where he served two terms. Four years later, he was elected to the Senate, where he served six terms. While generally adhering to conservative principles, McCain also gained a reputation as a "maverick" for his willingness to break from his party on certain issues, including LGBT rights, gun regulations, and campaign finance reform where his stances were more moderate than those of the party's base. McCain was investigated and largely exonerated in a political influence scandal of the 1980s as one of the Keating Five; he then made regulating the financing of political campaigns one of his signature concerns, which eventually resulted in passage of the McCain–Feingold Act in 2002. He was also known for his work in the 1990s to restore diplomatic relations with Vietnam. McCain chaired the Senate Commerce Committee from 1997 to 2001 and 2003 to 2005, where he opposed pork barrel spending and earmarks. He belonged to the bipartisan "Gang of 14", which played a key role in alleviating a crisis over judicial nominations.

McCain entered the race for the 2000 Republican presidential nomination, but lost a heated primary season contest to George W. Bush. He secured the 2008 Republican presidential nomination, beating fellow candidates Mitt Romney and Mike Huckabee, though he lost the general election to Barack Obama. McCain subsequently adopted more orthodox conservative stances and attitudes and largely opposed actions of the Obama administration, especially with regard to foreign policy matters. In 2015, he became Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. He refused to support then-Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election and later became a vocal critic of the Trump administration. While McCain opposed the Obama-era Affordable Care Act (ACA), he cast the deciding vote against the American Health Care Act of 2017, which would have partially repealed the ACA. After being diagnosed with glioblastoma in 2017, he reduced his role in the Senate to focus on treatment, dying from the disease in 2018.

Early life and military career (1936–1981)

Early life and education

John Sidney McCain III was born on August 29, 1936, at Coco Solo Naval Air Station in the Panama Canal Zone, to naval officer John S. McCain Jr. and Roberta Wright McCain. He had an older sister, Sandy, and a younger brother, Joe.[3] At that time, the Panama Canal was under U.S. control,[4] and he was granted U.S. citizenship at the age of eleven months.[5]

His father and his paternal grandfather, John S. McCain Sr., were also Naval Academy graduates and both became four-star admirals in the United States Navy.[6] The McCain family moved with their father as he took various naval postings in the United States and in the Pacific.[3][7] As a result, the younger McCain attended a total of about 20 schools.[8] In 1951, the family settled in Northern Virginia, and McCain attended Episcopal High School, a private preparatory boarding school in Alexandria.[9][10] He excelled at wrestling and graduated in 1954.[11][12] He referred to himself as an Episcopalian as recently as June 2007, after which date he said he came to identify as a Baptist.[13]

Following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, McCain entered the United States Naval Academy, where he was a friend and informal leader for many of his classmates[14] and sometimes stood up for targets of bullying.[6] He also fought as a lightweight boxer.[15] He earned the nickname "John Wayne" "for his attitude and popularity with the opposite sex."[16] McCain did well in academic subjects that interested him, such as literature and history, but studied only enough to pass subjects that gave him difficulty, such as mathematics.[6][17] He came into conflict with higher-ranking personnel and did not always obey the rules. "He collected demerits the way some people collect stamps."[16] His class rank (894 of 899) was not indicative of his intelligence nor his IQ, which had been tested to be 128 and 133.[14][18] McCain graduated in 1958.[14]

Naval training, first marriage, and Vietnam War assignment

McCain began his early military career when he was commissioned as an ensign, and started two and a half years of training at Pensacola to become a naval aviator.[19] While there, he earned a reputation as a man who partied.[8] He completed flight school in 1960, and became a naval pilot of ground-attack aircraft; he was assigned to A-1 Skyraider squadrons[20] aboard the aircraft carriers USS Intrepid and USS Enterprise[21] in the Caribbean and Mediterranean Seas.[22] McCain began as a sub-par flier[22] who was at times careless and reckless;[23] during the early to mid-1960s, two of his flight missions crashed, and a third mission collided with power lines, but he received no major injuries.[23] His aviation skills improved over time,[22] and he was seen as a good pilot, albeit one who tended to "push the envelope" in his flying.[23]

On July 3, 1965, McCain was 28 when he married Carol Shepp, who had worked as a runway model and secretary.[24] McCain adopted her two young children, Douglas and Andrew.[21][25] He and Carol then had a daughter, Sidney.[26][27] The same year, he was a one-day champion on the game show Jeopardy![28]

McCain requested a combat assignment,[29] and was assigned to the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal flying A-4 Skyhawks.[30] His combat duty began in mid-1967, when Forrestal was assigned to a bombing campaign, Operation Rolling Thunder, during the Vietnam War.[24][31] Stationed in the Gulf of Tonkin, McCain and his fellow pilots became frustrated by micromanagement from Washington; he later wrote, "In all candor, we thought our civilian commanders were complete idiots who didn't have the least notion of what it took to win the war."[31][32]

On July 29, 1967, McCain was a lieutenant commander when he was near the center of the USS Forrestal fire. He escaped from his burning jet and was trying to help another pilot escape when a bomb exploded;[33] McCain was struck in the legs and chest by fragments.[34] The ensuing fire killed 134 sailors.[35][36] With the Forrestal out of commission, McCain volunteered for assignment with the USS Oriskany, another carrier employed in Operation Rolling Thunder.[37] There, he was awarded the Navy Commendation Medal and the Bronze Star Medal for missions flown over North Vietnam.[38]

Prisoner of war

McCain was taken prisoner of war on October 26, 1967. He was flying his 23rd bombing mission over North Vietnam when his A-4E Skyhawk was shot down by a missile over Hanoi.[39][40] McCain fractured both arms and a leg when he ejected from the aircraft,[41] and nearly drowned after he parachuted into Trúc Bạch Lake. Some North Vietnamese pulled him ashore, then others crushed his shoulder with a rifle butt and bayoneted him.[39] McCain was then transported to Hanoi's main Hỏa Lò Prison, nicknamed the "Hanoi Hilton".[40]

Although McCain was seriously wounded and injured, his captors refused to treat him. They beat and interrogated him and he was given medical care only when the North Vietnamese discovered that his father was an admiral.[42] His status as a prisoner of war (POW) made the front pages of major American newspapers.[43][44]

McCain spent six weeks in the hospital, where he received marginal care. He had lost 50 pounds (23 kg), he was in a chest cast, and his gray hair had turned white.[39] McCain was sent to a different camp on the outskirts of Hanoi.[45] In December 1967, McCain was placed in a cell with two other Americans, who did not expect him to live more than a week.[46] In March 1968, McCain was placed in solitary confinement, where he remained for two years.[47]

In mid-1968, his father John S. McCain Jr. was named commander of all U.S. forces in the Vietnam theater, and the North Vietnamese offered McCain early release[48] because they wanted to appear merciful for propaganda purposes,[49] and also to show other POWs that elite prisoners were willing to be treated preferentially.[48] McCain refused repatriation unless every man taken in before him was also released. Such early release was prohibited by the POWs' interpretation of the military Code of Conduct, which states in Article III: "I will accept neither parole nor special favors from the enemy."[50] To prevent the enemy from using prisoners for propaganda, officers were to agree to be released in the order in which they were captured.[39]

Beginning in August 1968, McCain was subjected to severe torture.[51] He was bound and beaten every two hours, and he was suffering from heat exhaustion and dysentery.[39][51] Further injuries brought McCain to "the point of suicide", but his preparations were interrupted by guards. Eventually, McCain made an anti-U.S. propaganda "confession".[39] He had always felt that his statement was dishonorable, but as he later wrote: "I had learned what we all learned over there: every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine."[52][53] Many U.S. POWs were tortured and maltreated to extract "confessions" and propaganda statements;[54] virtually all eventually yielded something.[55] McCain received two to three beatings weekly because of his continued refusal to sign additional statements.[56]

McCain refused to meet various anti-war groups seeking peace in Hanoi, wanting to give neither them nor the North Vietnamese a propaganda victory.[57] From late 1969, treatment of McCain and many of the other POWs became more tolerable,[58] while McCain continued to resist the camp authorities.[59] McCain and other prisoners cheered the U.S. "Christmas Bombing" campaign of December 1972, viewing it as a forceful measure to push North Vietnam to terms.[53][60]

McCain was a prisoner of war in North Vietnam for five and a half years, until his release on March 14, 1973, along with 108 other prisoners of war.[61] His wartime injuries left him permanently incapable of raising his arms above his head.[62] After the war, McCain, accompanied by his family, returned to the site on a few occasions.[63]

Commanding officer, liaison to Senate, and second marriage

McCain was reunited with his family when he returned to the United States. His wife Carol had been severely injured by an automobile accident in December 1969. She was then four inches shorter, in a wheelchair or on crutches, and substantially heavier than when he had last seen her. As a returned POW, he became a celebrity of sorts.[64]

McCain underwent treatment for his injuries that included months of physical therapy.[65] He attended the National War College at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C., during 1973–1974.[66] He was rehabilitated by late 1974, and his flight status was reinstated. In 1976, he became Commanding Officer of a training squadron stationed in Florida.[64][67] He improved the unit's flight readiness and safety records,[68] and won the squadron its first-ever Meritorious Unit Commendation.[67] During this period in Florida, he had extramarital affairs, and his marriage began to falter, about which he later stated: "The blame was entirely mine".[69][70]

McCain served as the Navy's liaison to the U.S. Senate beginning in 1977.[71] In retrospect, he said that this represented his "real entry into the world of politics, and the beginning of my second career as a public servant."[64] His key behind-the-scenes role gained congressional financing for a new supercarrier against the wishes of the Carter administration.[65][72]

In April 1979,[65] McCain met Cindy Lou Hensley, a teacher from Phoenix, Arizona, whose father had founded a large beer distributorship.[70] They began dating, and he urged his wife, Carol, to grant him a divorce, which she did in February 1980; the uncontested divorce took effect in April 1980.[25][65] The settlement included two houses and financial support for her ongoing medical treatments due to her 1969 car accident; they remained on good terms.[70] McCain and Hensley were married on May 17, 1980, with Senators William Cohen and Gary Hart attending as groomsmen.[24][70] McCain's children did not attend, and several years passed before they reconciled.[27][65] John and Cindy McCain entered into a prenuptial agreement that kept most of her family's assets under her name; they kept their finances separate and filed separate income tax returns.[73]

McCain decided to leave the Navy. It was doubtful whether he would ever be promoted to the rank of full admiral, as he had poor annual physicals and had not been given a major sea command.[74] His chances of being promoted to rear admiral were better, but he declined that prospect, as he had already made plans to run for Congress and said he could "do more good there."[75][76]

McCain retired from the Navy as a captain on April 1, 1981.[38][77] He was designated as disabled and awarded a disability pension.[78] Upon leaving the military, he moved to Arizona. His numerous military decorations and awards include: the Silver Star, two Legion of Merits, Distinguished Flying Cross, three Bronze Star Medals, two Purple Hearts, two Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medals, and the Prisoner of War Medal.[38]

House and Senate elections and career (1982–2000)

U.S. Representative

McCain set his sights on becoming a representative because he was interested in current events, was ready for a new challenge, and had developed political ambitions.[70][79][80] Living in Phoenix, he went to work for his new father-in-law's large Anheuser-Busch beer distributorship.[70] As vice president of public relations at the distributorship, he gained political support among the local business community, meeting powerful figures such as banker Charles Keating Jr., real estate developer Fife Symington III (later Governor of Arizona) and newspaper publisher Darrow "Duke" Tully.[71] In 1982, McCain ran as a Republican for an open seat in Arizona's 1st congressional district, which was being vacated by 30-year incumbent Republican John Jacob Rhodes.[81] A newcomer to the state, McCain was termed a carpetbagger.[70] McCain responded to a voter making that charge with what a Phoenix Gazette columnist later described as "the most devastating response to a potentially troublesome political issue I've ever heard":[70]

Listen, pal. I spent 22 years in the Navy. My father was in the Navy. My grandfather was in the Navy. We in the military service tend to move a lot. We have to live in all parts of the country, all parts of the world. I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and living and spending my entire life in a nice place like the First District of Arizona, but I was doing other things. As a matter of fact, when I think about it now, the place I lived longest in my life was Hanoi.[70][82]

McCain won a highly contested primary election with the assistance of local political endorsements, his Washington connections, and money that his wife lent to his campaign.[70][71] He then easily won the general election in the heavily Republican district.[70]

In 1983, McCain was elected to lead the incoming group of Republican representatives,[70] and was assigned to the House Committee on Interior Affairs. Also that year, he opposed creation of a federal Martin Luther King Jr. Day, but admitted in 2008: "I was wrong and eventually realized that, in time to give full support [in 1990] for a state holiday in Arizona."[83][84]

At this point, McCain's politics were mainly in line with those of President Ronald Reagan; this included support for Reaganomics, and he was active on Indian Affairs bills.[85] He supported most aspects of the foreign policy of the Reagan administration, including its hardline stance against the Soviet Union and policy towards Central American conflicts, such as backing the Contras in Nicaragua.[85] McCain opposed keeping U.S. Marines deployed in Lebanon, citing unattainable objectives, and subsequently criticized President Reagan for pulling out the troops too late; in the interim, the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing killed hundreds.[70][86] McCain won re-election to the House easily in 1984,[70] and gained a spot on the House Foreign Affairs Committee.[87] In 1985, he made his first return trip to Vietnam,[88] and also traveled to Chile where he met with its military junta ruler, General Augusto Pinochet.[89][90][91]

Growing family

In 1984, McCain and Cindy had their first child, daughter Meghan, followed two years later by son John IV and in 1988 by son James.[92] In 1991, Cindy brought an abandoned three-month-old girl needing medical treatment to the U.S. from a Bangladeshi orphanage run by Mother Teresa.[93] The McCains decided to adopt her and named her Bridget.[94]

First two terms in the U.S. Senate

McCain's Senate career began in January 1987, after he defeated his Democratic opponent, former state legislator Richard Kimball, by 20 percentage points in the 1986 election.[71][95] McCain succeeded Arizona native, conservative icon, and the 1964 Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater upon Goldwater's retirement as U.S. senator from Arizona for 30 years.[95] In January 1988, McCain voted in favor of the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987,[96] and voted to override President Reagan's veto of that legislation the following March.[97]

Senator McCain became a member of the Armed Services Committee, with which he had formerly done his Navy liaison work; he also joined the Commerce Committee and the Indian Affairs Committee.[95] He continued to support the Native American agenda.[98] As first a House member and then a senator—and as a lifelong gambler with close ties to the gambling industry[99]—McCain was one of the main authors of the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act,[100][101] which codified rules regarding Native American gambling enterprises.[102] McCain was also a strong supporter of the Gramm–Rudman legislation that enforced automatic spending cuts in the case of budget deficits.[103]

McCain soon gained national visibility. He delivered a well-received speech at the 1988 Republican National Convention, was mentioned by the press as a short list vice-presidential running mate for Republican nominee George H. W. Bush, and was named chairman of Veterans for Bush.[95][104]

Keating Five

McCain became embroiled in a scandal during the 1980s, as one of five United States senators comprising the so-called Keating Five.[105] Between 1982 and 1987, McCain had received $112,000 in lawful[106] political contributions from Charles Keating Jr. and his associates at Lincoln Savings and Loan Association, along with trips on Keating's jets[105] that McCain belatedly repaid, in 1989.[107] In 1987, McCain was one of the five senators whom Keating contacted to prevent the government's seizure of Lincoln, and McCain met twice with federal regulators to discuss the government's investigation of Lincoln.[105] In 1999, McCain said: "The appearance of it was wrong. It's a wrong appearance when a group of senators appear in a meeting with a group of regulators, because it conveys the impression of undue and improper influence. And it was the wrong thing to do."[108] In the end, McCain was cleared by the Senate Ethics Committee of acting improperly or violating any law or Senate rule, but was mildly rebuked for exercising "poor judgment".[106][108][109]

In his 1992 re-election bid, the Keating Five affair was not a major issue,[110] and he won handily, gaining 56 percent of the vote to defeat Democratic community and civil rights activist Claire Sargent and independent former governor, Evan Mecham.[111]

Political independence

McCain developed a reputation for independence during the 1990s.[112] He took pride in challenging party leadership and establishment forces, becoming difficult to categorize politically.[112]

As a member of the 1991–1993 Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, chaired by fellow Vietnam War veteran and Democrat, John Kerry, McCain investigated the Vietnam War POW/MIA issue, to determine the fate of U.S. service personnel listed as missing in action during the Vietnam War.[113] The committee's unanimous report stated there was "no compelling evidence that proves that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia."[114] Helped by McCain's efforts, in 1995 the U.S. normalized diplomatic relations with Vietnam.[115] McCain was vilified by some POW/MIA activists who, despite the committee's unanimous report, believed many Americans were still held against their will in Southeast Asia.[115][116][117] From January 1993 until his death, McCain was Chairman of the International Republican Institute, an organization that supports the emergence of political democracy worldwide.[118]

In 1993 and 1994, McCain voted to confirm President Clinton's nominees to the U.S. Supreme Court, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, whom he considered qualified. He later explained that "under our Constitution, it is the president's call to make."[119] McCain had also voted to confirm nominees of presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, including Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas.[120]

Campaign finance reform

McCain attacked what he saw as the corrupting influence of large political contributions—from corporations, labor unions, other organizations, and wealthy individuals—and he made this his signature issue.[121] Starting in 1994, he worked with Democratic Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold on campaign finance reform; their McCain–Feingold bill attempted to put limits on "soft money".[121] The efforts of McCain and Feingold were opposed by some of the moneyed interests targeted, by incumbents in both parties, by those who felt spending limits impinged on free political speech and might be unconstitutional as well, and by those who wanted to counterbalance the power of what they saw as media bias.[121][122] Despite sympathetic coverage in the media, initial versions of the McCain–Feingold Act were filibustered and never came to a vote.[123]

The term "maverick Republican" was frequently applied to McCain, and he also used it himself.[121][124][125] In 1993, McCain opposed military operations in Somalia.[126] Another target of his was pork barrel spending by Congress, and he actively supported the Line Item Veto Act of 1996, which gave the president power to veto individual spending items[121] but was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1998.[127]

In the 1996 presidential election, McCain was again on the short list of possible vice-presidential picks, this time for Republican nominee Bob Dole.[110][128] While Dole instead selected Jack Kemp, he chose McCain to deliver the nominating speech for him in the presidential roll call vote at the 1996 Republican National Convention.[129] The following year, Time magazine named McCain as one of the "25 Most Influential People in America".[130]

In 1997, McCain became chairman of the powerful Senate Commerce Committee; he was criticized for accepting funds from corporations and businesses under the committee's purview, but in response said the small contributions he received were not part of the big-money nature of the campaign finance problem.[121] McCain took on the tobacco industry in 1998, proposing legislation to increase cigarette taxes to fund anti-smoking campaigns, discourage teenage smokers, increase money for health research studies, and help states pay for smoking-related health care costs.[121][131] Supported by the Clinton administration but opposed by the industry and most Republicans, the bill failed to gain cloture.[131]

Start of third term in the U.S. Senate

In November 1998, McCain won re-election to a third Senate term in a landslide over his Democratic opponent, environmental lawyer Ed Ranger.[121] In the February 1999 Senate trial following the impeachment of Bill Clinton, McCain voted to convict the president on both the perjury and obstruction of justice counts, saying Clinton had violated his sworn oath of office.[132] In March 1999, McCain voted to approve the NATO bombing campaign against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, saying that the ongoing genocide of the Kosovo War must be stopped and criticizing past Clinton administration inaction.[133] Later in 1999, McCain shared the Profile in Courage Award with Feingold for their work in trying to enact their campaign finance reform,[134] although the bill was still failing repeated attempts to gain cloture.[123]

In August 1999, McCain's memoir Faith of My Fathers, co-authored with Mark Salter, was published;[135] a reviewer observed that its appearance "seems to have been timed to the unfolding Presidential campaign."[136] The most successful of his writings, it received positive reviews,[137] became a bestseller,[138] and was later made into a TV film.[139] The book traces McCain's family background and childhood, covers his time at Annapolis and his service before and during the Vietnam War, concluding with his release from captivity in 1973. According to one reviewer, it describes "the kind of challenges that most of us can barely imagine. It's a fascinating history of a remarkable military family."[140]

2000 presidential campaign

McCain announced his candidacy for president on September 27, 1999, in Nashua, New Hampshire, saying he was staging "a fight to take our government back from the power brokers and special interests, and return it to the people and the noble cause of freedom it was created to serve".[135][141] The frontrunner for the Republican nomination was Texas Governor George W. Bush, who had the political and financial support of most of the party establishment, whereas McCain was supported by many moderate Republicans and some conservative Republicans.[142]

McCain focused on the New Hampshire primary, where his message appealed to independents.[143] He traveled on a campaign bus called the Straight Talk Express.[135] He held many town hall meetings, answering every question voters asked, in a successful example of "retail politics", and he used free media to compensate for his lack of funds.[135] One reporter later recounted that, "McCain talked all day long with reporters on his Straight Talk Express bus; he talked so much that sometimes he said things that he shouldn't have, and that's why the media loved him."[144] On February 1, 2000, he won New Hampshire's primary with 49 percent of the vote to Bush's 30 percent. The Bush campaign and the Republican establishment feared that a McCain victory in the crucial South Carolina primary might give his campaign unstoppable momentum.[135][145]

The Arizona Republic wrote that the McCain–Bush primary contest in South Carolina "has entered national political lore as a low-water mark in presidential campaigns", while The New York Times called it "a painful symbol of the brutality of American politics".[135][147][148] A variety of interest groups, which McCain had challenged in the past, ran negative ads.[135][149] Bush borrowed McCain's earlier language of reform,[150] and declined to dissociate himself from a veterans activist who accused McCain (in Bush's presence) of having "abandoned the veterans" on POW/MIA and Agent Orange issues.[135][151]

Incensed,[151] McCain ran ads accusing Bush of lying and comparing the governor to Bill Clinton, which Bush said was "about as low a blow as you can give in a Republican primary".[135] An anonymous smear campaign began against McCain, delivered by push polls, faxes, e-mails, flyers, and audience plants.[135][152] The smears claimed that McCain had fathered a black child out of wedlock (the McCains' dark-skinned daughter was adopted from Bangladesh), that his wife Cindy was a drug addict, that he was a homosexual, and that he was a "Manchurian Candidate" who was either a traitor or mentally unstable from his POW days.[135][147] The Bush campaign strongly denied any involvement with the attacks.[147][153]

McCain lost South Carolina on February 19, with 42 percent of the vote to Bush's 53 percent,[154] in part because Bush mobilized the state's evangelical voters[135][155] and outspent McCain.[156] The win allowed Bush to regain lost momentum.[154] McCain said of the rumor spreaders, "I believe that there is a special place in hell for people like those."[94] According to one acquaintance, the South Carolina experience left him in a "very dark place".[147]

McCain's campaign never completely recovered from his South Carolina defeat, although he did rebound partially by winning in Arizona and Michigan a few days later.[157] He made a speech in Virginia Beach that criticized Christian leaders, including Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell, as divisive conservatives,[147] declaring "we embrace the fine members of the religious conservative community. But that does not mean that we will pander to their self-appointed leaders."[158] McCain lost the Virginia primary on February 29,[159] and on March 7 lost nine of the thirteen primaries on Super Tuesday to Bush.[160] With little hope of overcoming Bush's delegate lead, McCain withdrew from the race on March 9, 2000.[161] He endorsed Bush two months later.[162]

Senate career (2000–2008)

Remainder of third Senate term

McCain began 2001 by breaking with the new administration on a number of matters, including HMO reform, climate change, and gun control legislation; McCain–Feingold was opposed by Bush as well.[123][163] In May 2001, McCain was one of only two Senate Republicans to vote against the Bush tax cuts.[163][164] Besides the differences with Bush on ideological grounds, there was considerable antagonism between the two remaining from the previous year's campaign.[165][166] When a Republican senator, Jim Jeffords, became an Independent, thereby throwing control of the Senate to the Democrats, McCain defended Jeffords against "self-appointed enforcers of party loyalty".[163] Indeed, there was speculation at the time, and in years since, about McCain himself leaving the Republican Party, but McCain had always adamantly denied that he ever considered doing so.[163][167][168] Beginning in 2001, McCain used political capital gained from his presidential run, as well as improved legislative skills and relationships with other members, to become one of the Senate's most influential members.[169]

After the September 11 attacks in 2008, McCain supported Bush and the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan.[163][170] He and Democratic senator Joe Lieberman wrote the legislation that created the 9/11 Commission,[171] while he and Democratic senator Fritz Hollings co-sponsored the Aviation and Transportation Security Act that federalized airport security.[172]

In March 2002, McCain–Feingold, officially known as the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, passed in both Houses of Congress and was signed into law.[123][163] It was McCain's greatest legislative achievement.[163][173]

Meanwhile, in discussions over proposed U.S. action against Iraq, McCain was a strong supporter of the Bush administration's position.[163] He stated that Iraq was "a clear and present danger" to the U.S., and voted for the Iraq War Resolution in October 2002.[163] He predicted that U.S. forces would be treated as liberators by many Iraqi people.[174] In May 2003, McCain voted against the second round of Bush tax cuts, saying it was unwise at a time of war.[164] By November 2003, after a trip to Iraq, he was publicly questioning Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, saying that more U.S. troops were needed; the following year, McCain announced that he had lost confidence in Rumsfeld.[175][176]

In October 2003, McCain and Lieberman co-sponsored the Climate Stewardship Act that would have introduced a cap and trade system aimed at returning greenhouse gas emissions to 2000 levels; the bill was defeated with 55 votes to 43 in the Senate.[177] They reintroduced modified versions of the Act two additional times, for the final time in January 2007 with the co-sponsorship of Barack Obama, among others.[178]

In the 2004 U.S. presidential election campaign, McCain was frequently mentioned for the vice-presidential slot, only this time as part of the Democratic ticket under nominee John Kerry.[179][180][181] McCain said that Kerry had never formally offered him the position and that he would not have accepted it.[180][181][182] At the 2004 Republican National Convention, McCain supported Bush for re-election, praising Bush's management of the War on Terror since the September 11 attacks.[183] At the same time, he defended Kerry's Vietnam War record.[184] By August 2004, McCain had the best favorable-to-unfavorable rating (55 percent to 19 percent) of any national politician;[183] he campaigned for Bush much more than he had four years previously, though the two remained situational allies rather than friends.[165]

McCain was also up for re-election as senator, in 2004. He defeated little-known Democratic schoolteacher Stuart Starky with his biggest margin of victory, garnering 77 percent of the vote.[185]

Start of fourth Senate term

In May 2005, McCain led the so-called Gang of 14 in the Senate, which established a compromise that preserved the ability of senators to filibuster judicial nominees, but only in "extraordinary circumstances".[186] The compromise took the steam out of the filibuster movement, but some Republicans remained disappointed that the compromise did not eliminate filibusters of judicial nominees in all circumstances.[187] McCain subsequently cast Supreme Court confirmation votes in favor of John Roberts and Samuel Alito, calling them "two of the finest justices ever appointed to the United States Supreme Court."[120]

Breaking from his 2001 and 2003 votes, McCain supported the Bush tax cut extension in May 2006, saying not to do so would amount to a tax increase.[164] Working with Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy, McCain was a strong proponent of comprehensive immigration reform, which would involve legalization, guest worker programs, and border enforcement components. The Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act was never voted on in 2005, while the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2006 passed the Senate in May 2006 but failed in the House.[176] In June 2007, President Bush, McCain, and others made the strongest push yet for such a bill, the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, but it aroused intense grassroots opposition among talk radio listeners and others, some of whom furiously characterized the proposal as an "amnesty" program,[188] and the bill twice failed to gain cloture in the Senate.[189]

By the middle of the 2000s (decade), the increased Indian gaming that McCain had helped bring about was a $23 billion industry.[101] He was twice chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, in 1995–1997 and 2005–2007, and his Committee helped expose the Jack Abramoff Indian lobbying scandal.[190][191] By 2005 and 2006, McCain was pushing for amendments to the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act which would have limited creation of off-reservation casinos,[101] and also limited the movement of tribes across state lines to build casinos.[192]

Owing to his time as a POW, McCain was recognized for his sensitivity to the detention and interrogation of detainees in the War on Terror. An opponent of the Bush administration's use of torture and detention without trial at Guantánamo Bay, saying: "some of these guys are terrible, terrible killers and the worst kind of scum of humanity. But, one, they deserve to have some adjudication of their cases ... even Adolf Eichmann got a trial".[193] In October 2005, McCain introduced the McCain Detainee Amendment to the Defense Appropriations bill for 2005, and the Senate voted 90–9 to support the amendment.[194] It prohibits inhumane treatment of prisoners, including prisoners at Guantánamo, by confining military interrogations to the techniques in the U.S. Army Field Manual on Interrogation. Although Bush had threatened to veto the bill if McCain's amendment was included,[195] the President announced in December 2005 that he accepted McCain's terms and would "make it clear to the world that this government does not torture and that we adhere to the international convention of torture, whether it be here at home or abroad".[196] This stance, among others, led to McCain being named by Time magazine in 2006 as one of America's 10 Best Senators.[197] McCain voted in February 2008 against a bill containing a ban on waterboarding,[198] which provision was later narrowly passed and vetoed by Bush. However, the bill in question contained other provisions to which McCain objected, and his spokesman stated: "This wasn't a vote on waterboarding. This was a vote on applying the standards of the [Army] field manual to CIA personnel."[198]

Meanwhile, McCain continued questioning the progress of the war in Iraq. In September 2005, he remarked upon Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Richard Myers' optimistic outlook on the war's progress: "Things have not gone as well as we had planned or expected, nor as we were told by you, General Myers."[199] In August 2006, he criticized the administration for continually understating the effectiveness of the insurgency: "We [have] not told the American people how tough and difficult this could be."[176] From the beginning, McCain strongly supported the Iraq troop surge of 2007.[200] The strategy's opponents labeled it "McCain's plan"[201] and University of Virginia political science professor Larry Sabato said, "McCain owns Iraq just as much as Bush does now."[176] The surge and the war were unpopular during most of the year, even within the Republican Party,[202] as McCain's presidential campaign was underway; faced with the consequences, McCain frequently responded, "I would much rather lose a campaign than a war."[203] In March 2008, McCain credited the surge strategy with reducing violence in Iraq, as he made his eighth trip to that country since the war began.[204]

2008 presidential campaign

McCain formally announced his intention to run for President of the United States on April 25, 2007, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.[205] He stated that: "I'm not running for president to be somebody, but to do something; to do the hard but necessary things, not the easy and needless things."[206]

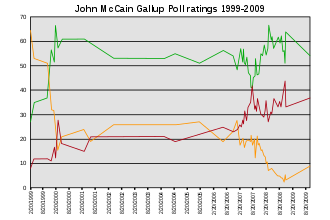

McCain's oft-cited strengths as a presidential candidate for 2008 included national name recognition, sponsorship of major lobbying and campaign finance reform initiatives, his ability to reach across the aisle, his well-known military service and experience as a POW, his experience from the 2000 presidential campaign, and an expectation that he would capture Bush's top fundraisers.[207] During the 2006 election cycle, McCain had attended 346 events[62] and helped raise more than $10.5 million on behalf of Republican candidates. McCain also became more willing to ask business and industry for campaign contributions, while maintaining that such contributions would not affect any official decisions he would make.[208] Despite being considered the front-runner for the nomination by pundits as 2007 began,[209] McCain was in second place behind former Mayor of New York City Rudy Giuliani in national Republican polls as the year progressed.

McCain had fundraising problems in the first half of 2007, due in part to his support for the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, which was unpopular among the Republican base electorate.[210][211] Large-scale campaign staff downsizing took place in early July, but McCain said that he was not considering dropping out of the race.[211] Later that month, the candidate's campaign manager and campaign chief strategist both departed.[212] McCain slumped badly in national polls, often running third or fourth with 15 percent or less support.

The Arizona senator subsequently resumed his familiar position as a political underdog,[213] riding the Straight Talk Express and taking advantage of free media such as debates and sponsored events.[214] By December 2007, the Republican race was unsettled, with none of the top-tier candidates dominating the race and all of them possessing major vulnerabilities with different elements of the Republican base electorate.[215] McCain was showing a resurgence, in particular with renewed strength in New Hampshire—the scene of his 2000 triumph—and was bolstered further by the endorsements from The Boston Globe, the New Hampshire Union Leader, and almost two dozen other state newspapers,[216] as well as from Senator Lieberman (now an Independent Democrat).[217] McCain decided not to campaign significantly in the January 3, 2008, Iowa caucuses, which saw a win by former Governor of Arkansas Mike Huckabee.

McCain's comeback plan paid off when he won the New Hampshire primary on January 8, defeating former Governor of Massachusetts Mitt Romney in a close contest, to once again become one of the front-runners in the race.[218] In mid-January, McCain placed first in the South Carolina primary, narrowly defeating Mike Huckabee.[219] Pundits credited the third-place finisher, Tennessee's former U.S. Senator Fred Thompson, with drawing votes from Huckabee in South Carolina, thereby giving a narrow win to McCain.[220] A week later, McCain won the Florida primary,[221] beating Romney again in a close contest; Giuliani then dropped out and endorsed McCain.[222]

On February 5, McCain won both the majority of states and delegates in the Super Tuesday Republican primaries, giving him a commanding lead toward the Republican nomination. Romney departed from the race on February 7.[223] McCain's wins in the March 4 primaries clinched a majority of the delegates, and he became the presumptive Republican nominee.[224]

Had he been elected, he would have become the first president physically born outside the United States. This raised a potential legal issue, since the United States Constitution requires the president to be a natural-born citizen. A bipartisan legal review,[225] and a unanimous but non-binding Senate resolution,[226] both concluded that he was a natural-born citizen. However, other legal scholars came to the opposite conclusion that although he was a citizen, at the time of his birth he was not a natural-born citizen, because the 1937 law that made him a citizen was passed one year after his birth.[227][228]

If inaugurated in 2009 at the age of 72 years and 144 days, he would have been the oldest person to become president.[229] McCain addressed concerns about his age and past health issues, stating in 2005 that his health was "excellent".[230] He had been treated for melanoma and an operation in 2000 for that condition left a noticeable mark on the left side of his face.[231] McCain's prognosis appeared favorable, according to independent experts, especially because he had already survived without a recurrence for more than seven years.[231] In May 2008, McCain's campaign briefly let the press review his medical records, and he was described as appearing cancer-free, having a strong heart, and in general being in good health.[232]

McCain clinched enough delegates for the nomination and his focus shifted toward the general election, while Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton fought a prolonged battle for the Democratic nomination.[233] McCain introduced various policy proposals, and sought to improve his fundraising.[234][235] Cindy McCain, who accounted for most of the couple's wealth with an estimated net worth of $100 million,[73] made part of her tax returns public in May.[236] After facing criticism about lobbyists on staff, the McCain campaign issued new rules in May 2008 to avoid conflicts of interest, causing five top aides to leave.[237][238]

When Obama became the Democrats' presumptive nominee in early June, McCain proposed joint town hall meetings, but Obama instead requested more traditional debates for the fall.[239] In July, a staff shake-up put Steve Schmidt in full operational control of the McCain campaign.[240] Rick Davis remained as campaign manager but with a reduced role. Davis had also managed McCain's 2000 presidential campaign; in 2005 and 2006, U.S. intelligence warned McCain's Senate staff about Davis's Russian links but gave no further warnings.[241][242][243][244]

Throughout the summer of 2008, Obama typically led McCain in national polls by single-digit margins,[245] and also led in several key swing states.[246] McCain reprised his familiar underdog role, which was due at least in part to the overall challenges Republicans faced in the election year.[213][246] McCain accepted public financing for the general election campaign, and the restrictions that go with it, while criticizing his Democratic opponent for becoming the first major party candidate to opt out of such financing for the general election since the system was implemented in 1976.[247][248] The Republican's broad campaign theme focused on his experience and ability to lead, compared to Obama's.[249]

On August 29, 2008, McCain revealed Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as his surprise choice for a running mate.[250] McCain was only the second U.S. major-party presidential nominee (after Walter Mondale, who chose Geraldine Ferraro) to select a woman as his running mate and the first Republican to do so. On September 3, 2008, McCain and Palin became the Republican Party's presidential and vice presidential nominees at the 2008 Republican National Convention in Saint Paul, Minnesota. McCain surged ahead of Obama in national polls following the convention, as the Palin pick energized core Republican voters who had previously been wary of him.[251] However, by the campaign's own later admission, the rollout of Palin to the national media went poorly,[252] and voter reactions to Palin grew increasingly negative, especially among independents and other voters concerned about her qualifications.[253]

McCain's decision to choose Sarah Palin as his running mate was criticized; New York Times journalist David Brooks said that "he took a disease that was running through the Republican party – anti-intellectualism, disrespect for facts – and he put it right at the centre of the party".[254] Laura McGann in Vox says that McCain gave the "reality TV politics" and Tea Party movement more political legitimacy, as well as solidifying "the Republican Party's comfort with a candidate who would say absurdities ... unleashing a political style and a values system that animated the Tea Party movement and laid the groundwork for a Trump presidency."[255] Although McCain later expressed regret for not choosing the independent Senator Joe Lieberman (who had previously been Al Gore's running mate in 2000, while still elected as a Democrat) as his VP candidate instead, he consistently defended Palin's performances at his events.[256]

On September 24, McCain said he was temporarily suspending his campaign activities, called on Obama to join him, and proposed delaying the first of the general election debates with Obama, to work on the proposed U.S. financial system bailout before Congress, which was targeted at addressing the subprime mortgage crisis and the financial crisis of 2007–2008.[257][258] McCain's intervention helped to give dissatisfied House Republicans an opportunity to propose changes to the plan that was otherwise close to agreement.[259][260] After Obama declined McCain's suspension suggestion, McCain went ahead with the debate on September 26.[261] On October 1, McCain voted in favor of a revised $700 billion rescue plan.[262] Another debate was held on October 7; like the first one, polls afterward suggested that Obama had won it.[263] A final presidential debate occurred on October 15.[264] Down the stretch, McCain was outspent by Obama by a four-to-one margin.[265]

During and after the final debate, McCain compared Obama's proposed policies to socialism and often invoked "Joe the Plumber" as a symbol of American small business dreams that would be thwarted by an Obama presidency.[266][267] He barred using the Jeremiah Wright controversy in ads against Obama,[268] but the campaign did frequently criticize Obama regarding his purported relationship with Bill Ayers.[269] McCain's rallies became increasingly vitriolic,[270] with attendees denigrating Obama and displaying a growing anti-Muslim and anti-African-American sentiment.[271] During a campaign rally in Minnesota, Gayle Quinnell, a McCain supporter, told him she did not trust Obama because "he's an Arab".[272] McCain replied, "No ma'am. He's a decent family man, citizen, that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues."[271] McCain's response was considered one of the finer moments of the campaign and was still being viewed several years later as a marker for civility in American politics, particularly in light of the anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant animus of the Donald Trump presidency.[270][273] Meghan McCain said that she cannot "go a day without someone bringing up (that) moment," and noted that at the time "there were a lot of people really trying to get my dad to go (against Obama) with ... you're a Muslim, you're not an American aspect of that," but that her father had refused. "I can remember thinking that it was a morally amazing and beautiful moment, but that maybe there would be people in the Republican Party that would be quite angry," she said.[274]

The election took place on November 4, and Barack Obama was declared the projected winner at about 11:00 pm Eastern Standard Time; McCain delivered his concession speech in Phoenix, Arizona, about twenty minutes later.[275] In it, he noted the historic and special significance of Obama being elected the nation's first African American president.[275] McCain remarked, "Whatever our differences, we are fellow Americans; and please believe me when I say, no association has ever meant more to me than that."[276] In the end, McCain won 173 electoral votes to Obama's 365;[277] McCain failed to win most of the battleground states and lost some traditionally Republican ones.[278] McCain gained 46 percent of the nationwide popular vote, compared to Obama's 53 percent.[278]

Senate career after 2008

Remainder of fourth Senate term

Following his defeat, McCain returned to the Senate amid varying views about what role he might play there.[279] McCain indicated that he intended to run for re-election to his Senate seat in 2010.[280] As the inauguration neared, Obama consulted with McCain on a variety of matters, to an extent rarely seen between a president-elect and his defeated rival,[281] and President Obama's inauguration speech contained an allusion to McCain's theme of finding a purpose greater than oneself.[282]

Nevertheless, McCain emerged as a leader of the Republican opposition to the Obama economic stimulus package of 2009, saying it incorporated federal policy changes that had nothing to do with near-term job creation and would expand the growing federal budget deficit.[283] McCain also voted against Obama's Supreme Court nomination of Sonia Sotomayor—saying that while undeniably qualified, "I do not believe that she shares my belief in judicial restraint"[284]—and by August 2009 was siding more often with his Republican Party on closely divided votes than ever before in his senatorial career.[285] McCain reasserted that the War in Afghanistan was winnable[286] and criticized Obama for a slow process in deciding whether to send additional troops there.[287]

McCain also harshly criticized Obama for scrapping construction of the U.S. missile defense complex in Poland, declined to enter negotiations over climate change legislation similar to what he had proposed in the past, and strongly opposed the Obama health care plan.[287][288] McCain led a successful filibuster of a measure that would allow repeal of the military's "Don't ask, don't tell" policy towards gays.[289] Factors involved in McCain's new direction included Senate staffers leaving, a renewed concern over national debt levels and the scope of federal government, a possible Republican primary challenge from conservatives in 2010, and McCain's campaign edge being slow to wear off.[287][288] As one longtime McCain advisor said, "A lot of people, including me, thought he might be the Republican building bridges to the Obama Administration. But he's been more like the guy blowing up the bridges."[287]

In early 2010, a primary challenge from radio talk show host and former U.S. Congressman J. D. Hayworth materialized in the Senate election in Arizona and drew support from some but not all elements of the Tea Party movement.[290][291] With Hayworth using the campaign slogan "The Consistent Conservative", McCain said—despite his own past use of the term on a number of occasions[291][292]—"I never considered myself a maverick. I consider myself a person who serves the people of Arizona to the best of his abilities."[293] The primary challenge coincided with McCain reversing or muting his stance on some issues such as the bank bailouts, closing of the Guantánamo Bay detention camp, campaign finance restrictions, and gays in the military.[290]

When the health care plan, now called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, passed Congress and became law in March 2010, McCain strongly opposed the landmark legislation not only on its merits but also on the way it had been handled in Congress. As a consequence, he warned that congressional Republicans would not work with Democrats on anything else: "There will be no cooperation for the rest of the year. They have poisoned the well in what they've done and how they've done it."[294] McCain became a vocal defender of Arizona SB 1070, the April 2010 tough anti-illegal immigration state law that aroused national controversy, saying that the state had been forced to take action given the federal government's inability to control the border.[291][295] In the August 24 primary, McCain beat Hayworth by a 56 to 32 percent margin.[296] McCain easily defeated Democratic Tucson city councilman Rodney Glassman in the general election.[297]

In the lame duck session of the 111th Congress, McCain voted for the compromise Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010,[298] but against the DREAM Act (which he had once sponsored) and the New START Treaty.[299] Most prominently, he continued to lead the eventually losing fight against "Don't ask, don't tell" repeal.[300] In his opposition, he sometimes fell into anger or hostility on the Senate floor, and called its passage "a very sad day" that would compromise the battle effectiveness of the military.[299][300]

Fifth Senate term

While control of the House of Representatives went over to the Republicans in the 112th Congress, the Senate stayed Democratic and McCain continued to be the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee. As the Arab Spring took center stage, McCain urged that the embattled Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, step down and thought the U.S. should push for democratic reforms in the region despite the associated risks of religious extremists gaining power.[301] McCain was an especially vocal supporter of the 2011 military intervention in Libya. In April of that year he visited the Anti-Gaddafi forces and National Transitional Council in Benghazi, the highest-ranking American to do so, and said that the rebel forces were "my heroes".[302] In June, he joined with Senator Kerry in offering a resolution that would have authorized the military intervention, and said: "The administration's disregard for the elected representatives of the American people on this matter has been troubling and counterproductive."[303][304] In August, McCain voted for the Budget Control Act of 2011 that resolved the U.S. debt ceiling crisis.[305] In November, McCain and Senator Carl Levin were leaders in efforts to codify in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 that terrorism suspects, no matter where captured, could be detained by the U.S. military and its tribunal system; following objections by civil libertarians, some Democrats, and the White House, McCain and Levin agreed to language making it clear that the bill would not pertain to U.S. citizens.[306][307]

In the 2012 Republican Party presidential primaries, McCain endorsed former 2008 rival Mitt Romney and campaigned for him, but compared the contest to a Greek tragedy due to its drawn-out nature with massive super PAC-funded attack ads damaging all the contenders.[308] He labeled the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision as "uninformed, arrogant, naïve", and, decrying its effects and the future scandals he thought it would bring, said it would become considered the court's "worst decision ... in the 21st century".[309] McCain took the lead in opposing the defense spending sequestrations brought on by the Budget Control Act of 2011 and gained attention for defending State Department aide Huma Abedin against charges brought by a few House Republicans that she had ties to the Muslim Brotherhood.[310]

McCain continued to be one of the most frequently appearing guests on the Sunday morning news talk shows.[310] He became one of the most vocal critics of the Obama administration's handling of the 2012 attack on the U.S. diplomatic mission in Benghazi, saying it was a "debacle" that featured either "a massive cover-up or incompetence that is not acceptable" and that it was worse than the Watergate scandal.[312] As an outgrowth of this strong opposition, he and a few other senators were successful in blocking the planned nomination of Ambassador to the UN Susan Rice to succeed Hillary Rodham Clinton as U.S. Secretary of State; McCain's friend John Kerry was nominated instead.[313]

Regarding the Syrian civil war that had begun in 2011, McCain repeatedly argued for the U.S. intervening militarily in the conflict on the side of the anti-government forces. He staged a visit to rebel forces inside Syria in May 2013, the first senator to do so, and called for arming the Free Syrian Army with heavy weapons and for the establishment of a no-fly zone over the country. Following reports that two of the people he posed for pictures with had been responsible for the kidnapping of eleven Lebanese Shiite pilgrims the year before, McCain disputed one of the identifications and said he had not met directly with the other.[314] Following the 2013 Ghouta chemical weapons attack, McCain argued again for strong American military action against the government of the Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad, and in September 2013 cast a Foreign Relations committee vote in favor of Obama's request to Congress that it authorize a military response.[315] McCain took the lead in criticizing a growing non-interventionist movement within the Republican Party, exemplified by his March 2013 comment that Senators Rand Paul and Ted Cruz and Representative Justin Amash were "wacko birds".[316]

During 2013, McCain was a member of a bi-partisan group of senators, the "Gang of Eight", which announced principles for another try at comprehensive immigration reform.[317] The resulting Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013 passed the Senate by a 68–32 margin, but faced an uncertain future in the House.[318] In July 2013, McCain was at the forefront of an agreement among senators to drop filibusters against Obama administration executive nominees without Democrats resorting to the "nuclear option" that would disallow such filibusters altogether.[319][320] However, the option would be imposed later in the year anyway, to the senator's displeasure.[321] These developments and some other negotiations showed that McCain had become the leader of a power center in the Senate for cutting deals in an otherwise bitterly partisan environment.[322][323][324] They also led some observers to conclude that the "maverick" McCain had returned.[320][324]

McCain was publicly skeptical about the Republican strategy that precipitated the U.S. federal government shutdown of 2013 and U.S. debt-ceiling crisis of 2013 to defund or delay the Affordable Care Act; in October 2013 he voted in favor of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014, which resolved them and said, "Republicans have to understand we have lost this battle, as I predicted weeks ago, that we would not be able to win because we were demanding something that was not achievable."[325] He was one of nine Republican senators who voted for the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 at the end of the year.[326] By early 2014, McCain's apostasies were enough that the Arizona Republican Party formally censured him for having what they saw as a liberal record that had been "disastrous and harmful".[327] McCain remained stridently opposed to many aspects of Obama's foreign policy, however, and in June 2014, following major gains by the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant in the 2014 Northern Iraq offensive, decried what he saw as a U.S. failure to protect its past gains in Iraq and called on the president's entire national security team to resign. McCain said, "Could all this have been avoided? ... The answer is absolutely yes. If I sound angry it's because I am angry."[328]

McCain was a supporter of the Euromaidan protests against Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych and his government, and appeared in Independence Square in Kyiv in December 2013.[329] Following the overthrow of Yanukovych and subsequent 2014 Russian military intervention in Ukraine, McCain became a vocal supporter of providing arms to Ukrainian military forces, saying the sanctions imposed against Russia were not enough.[330] In 2014, McCain led the opposition to the appointments of Colleen Bell, Noah Mamet, and George Tsunis to the ambassadorships in Hungary, Argentina, and Norway, respectively, arguing they were unqualified.[331] Unlike many Republicans, McCain supported the release and contents of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture in December 2014, saying "The truth is sometimes a hard pill to swallow. It sometimes causes us difficulties at home and abroad. It is sometimes used by our enemies in attempts to hurt us. But the American people are entitled to it, nonetheless."[332] He added that the CIA's practices following the September 11 attacks had "stained our national honor" while doing "much harm and little practical good" and that "Our enemies act without conscience. We must not."[333] He opposed the Obama administration's December 2014 decision to normalize relations with Cuba.[334]

The 114th United States Congress assembled in January 2015 with Republicans in control of the Senate, and McCain achieved one of his longtime goals when he became chairman of the Armed Services Committee.[335] In this position, he led the writing of proposed Senate legislation that sought to modify parts of the Goldwater–Nichols Act of 1986 to return responsibility for major weapons systems acquisition back to the individual armed services and their secretaries and away from the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics.[336] As chair, McCain tried to maintain a bipartisan approach and forged a good relationship with ranking member Jack Reed.[335] In April 2015, McCain announced that he would run for a sixth term in Arizona's 2016 Senate election.[337] During 2015, McCain strongly opposed the Obama administration's proposed comprehensive agreement on the Iranian nuclear program (later finalized as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)), saying that Secretary of State Kerry was "delusional" and "giv[ing] away the store" in negotiations with Iran.[338] McCain supported the Saudi Arabian-led military intervention in Yemen against the Houthis and forces loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh.[339]

McCain accused President Obama of being "directly responsible" for the Orlando nightclub shooting "because when he pulled everybody out of Iraq, al-Qaeda went to Syria, became ISIS, and ISIS is what it is today thanks to Barack Obama's failures."[340][341]

During the 2016 Republican primaries, McCain said he would support the Republican nominee even if it was Donald Trump, in spite of his personal disagreements with Trump.

However, following Mitt Romney's 2016 anti-Trump speech, McCain endorsed the sentiments expressed in that speech, saying he had serious concerns about Trump's "uninformed and indeed dangerous statements on national security issues".[342] Relations between the two had been fraught since early in Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, when McCain referred to a room full of Trump supporters as "crazies", and the real estate mogul then said of McCain: "He insulted me, and he insulted everyone in that room ... He is a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren't captured ... perhaps he was a war hero, but right now he's said a lot of very bad things about a lot of people."[342][343] This was widely condemned by much of the Republican Party, with Senator Marco Rubio referring to Trump's comments as "offensive rantings", commentator Rick Santorum tweeting that "@SenJohnMcCain is an American hero, period", and Governor Scott Walker using the comments as the basis for his denunciation of Trump in a campaign event in Sioux City.[344] Following Trump becoming the presumptive nominee of the party on May 3, McCain said that Republican voters had spoken and he would support Trump.[345]

McCain himself faced a primary challenge from Kelli Ward, a fervent Trump supporter, and then was expected to face a potentially strong challenge from Democratic Congresswoman Ann Kirkpatrick in the general election.[346] The senator privately expressed worry over the effect that Trump's unpopularity among Hispanic voters might have on his own chances but also was concerned with more conservative pro-Trump voters; he thus kept his endorsement of Trump in place but tried to speak of him as little as possible given their disagreements.[347][348][349] However McCain defeated Ward in the primary by a double-digit percentage point margin and gained a similar lead over Kirkpatrick in general election polls, and when the Donald Trump Access Hollywood controversy broke, he felt secure enough to on October 8 withdraw his endorsement of Trump.[346] McCain stated that Trump's "demeaning comments about women and his boasts about sexual assaults" made it "impossible to continue to offer even conditional support" and added that he would not vote for Hillary Clinton, but would instead "write in the name of some good conservative Republican who is qualified to be president."[350][351] McCain defeated Kirkpatrick, securing a sixth term as United States Senator from Arizona.[352]

In November 2016, McCain obtained a copy of a dossier regarding the Trump presidential campaign's links to Russia compiled by Christopher Steele.[353] In December 2016, McCain passed on the dossier to FBI Director James Comey. McCain later wrote that he felt the dossier's "allegations were disturbing" but unverifiable by himself, so he let the FBI investigate.[354]

Sixth and final Senate term

McCain chaired the January 5, 2017, hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee where Republican and Democratic senators and intelligence officers, including James R. Clapper Jr., the Director of National Intelligence, Michael S. Rogers, the head of the National Security Agency and United States Cyber Command presented a "united front" that "forcefully reaffirmed the conclusion that the Russian government used hacking and leaks to try to influence the presidential election."[356]

McCain visited the American missile destroyer USS John S McCain, which docked in Vietnam on 2 June 2017.[357]

In June 2017, McCain voted to support President Trump's controversial arms deal with Saudi Arabia.[358][359]

Repeal and replacement of Obamacare was a centerpiece of McCain's 2016 re-election campaign,[360] and in July 2017, he said, "Have no doubt: Congress must replace Obamacare, which has hit Arizonans with some of the highest premium increases in the nation and left 14 of Arizona's 15 counties with only one provider option on the exchanges this year."[361]

In September 2017, as the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar became ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya Muslim minority, McCain announced moves to scrap planned future military cooperation with Myanmar.[362]

In October 2017, McCain praised President Trump's decision to decertify Iran's compliance with the Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA) while not yet withdrawing the U.S. from the agreement, saying that the Obama-era policy failed "to meet the multifaceted threat Iran poses. The goals President Trump presented in his speech today are a welcomed long overdue change."[363]

Brain tumor diagnosis and surgery

On July 14, 2017, McCain underwent a minimally invasive craniotomy at Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, Arizona, to remove a blood clot above his left eye. His absence prompted Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to delay a vote on the Better Care Reconciliation Act.[364] Five days later, Mayo Clinic doctors announced the presence of a glioblastoma, which is a very aggressive cancerous brain tumor.[365] Even with treatment, average survival time is approximately 14 months.[365] McCain was a survivor of previous cancers, including melanoma.[231][366]

President Donald Trump publicly wished Senator McCain well,[367] as did many others, including former president Obama.[368] On July 19, McCain's senatorial office issued a statement that he "appreciates the outpouring of support he has received over the last few days. He is in good spirits as he continues to recover at home ... and is confident that any future treatment will be effective."[369]

Return to the Senate

McCain returned to the Senate on July 25, less than two weeks after brain surgery. He cast a deciding vote allowing the Senate to begin consideration of bills to replace the Affordable Care Act. He delivered a speech criticizing the party-line voting process and urged a "return to regular order" using the usual committee hearings and deliberations.[370][371][372] On July 28, he cast the decisive vote against the Republicans' final proposal that month, the so-called "skinny repeal" option, which failed 49–51.[373] McCain supported the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

McCain did not vote in the Senate after December 2017, remaining in Arizona to undergo cancer treatment. On April 15, 2018, he underwent surgery for an infection relating to diverticulitis.[374]

Committee assignments

- Committee on Armed Services (Chair)

- as chair of the full committee may serve as an ex-officio member of any subcommittee

- Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

- Committee on Indian Affairs

- Committee on Intelligence (ex-officio)

Caucus memberships

- International Conservation Caucus

- Senate Diabetes Caucus

- Senate National Security Caucus (Co-chair)

- Sportsmen's Caucus

- Senate Wilderness and Public Lands Caucus

- Senate Ukraine Caucus[375]

- Republican Main Street Partnership.[376]

Death and funeral

On August 24, 2018, McCain's family announced that he would no longer receive treatment for his cancer.[377] He died the following day at his home in Cornville, Arizona.[378][379]

McCain lay in state in the Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix on August 29, which would have been his 82nd birthday. This was followed by a service at North Phoenix Baptist Church on August 30. His remains were then moved to Washington, D.C., to lie in state in the United States Capitol rotunda[380] on August 31, which was followed by a service at the Washington National Cathedral on September 1. He was a "lifelong Episcopalian" who attended, but did not join, a Southern Baptist church for at least 17 years; memorial services were scheduled in both denominations.[381][382]

Prior to his death, McCain requested that former presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama deliver eulogies at his funeral and asked that neither President Donald Trump nor his former running mate Sarah Palin attend any of the services.[383][384] McCain himself planned the funeral arrangements and selected his pallbearers for the service in Washington, including former vice president and former Delaware Senator (and future president) Joe Biden, former Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold, former Secretary of Defense William Cohen, actor Warren Beatty, and Russian dissident Vladimir Kara-Murza.[385]

Multiple foreign leaders attended McCain's service: Secretary General of NATO Jens Stoltenberg, President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko, Speaker of Taiwan's Congress Su Jia-chyuan, National Defense Minister of Canada Harjit Sajjan, defense minister Jüri Luik and foreign minister Sven Mikser of Estonia, Foreign Minister of Latvia Edgars Rinkēvičs, Foreign Minister of Lithuania Linas Antanas Linkevičius, and Foreign Affairs Minister of Saudi Arabia Adel al-Jubeir.[386][387][388]

Dignitaries who gave eulogies at the Memorial Service in Washington National Cathedral included Barack Obama, George W. Bush, Henry Kissinger, Joe Lieberman, and his daughter Meghan McCain. The New Yorker described the service as the biggest meeting of anti-Trump figures during his presidency.[389] Those who attended the funeral included former United States presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush, Bill Clinton; First Ladies Michelle Obama, Laura Bush, Hillary Clinton; and former vice presidents Joe Biden, Dick Cheney, Al Gore, and Dan Quayle. Former president Jimmy Carter and former vice president Walter Mondale did not attend; former president George H. W. Bush was too ill to attend the service; and President Trump was not invited. Other attendees included Tom Brokaw, Charlie Rose, Bob Dole, Madeleine Albright, John Kerry, Mitch McConnell, Paul Ryan, Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, Mitt Romney, Lindsey Graham, Warren Beatty, Elizabeth Warren, Jay Leno, and Kamala Harris. President Trump's daughter and son-in-law Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner attended to the displeasure of Meghan McCain.[390][391]

On September 2, the funeral cortege traveled from Washington, D.C., through Annapolis, Maryland, to the Naval Academy.[392] A private service was held at the Naval Academy Chapel and McCain was buried at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery.[393]

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) announced that he would introduce a resolution to rename the Russell Senate Office Building after McCain.[394] A quarter peal of Grandsire Caters in memory of McCain was rung by the bellringers of Washington National Cathedral the day following his death.[395] Another memorial quarter peal was rung on September 6 on the Bells of Congress at the Old Post Office in Washington.[396]