Kinshasa

Kinshasa | |

|---|---|

Capital city and Province | |

| Ville de Kinshasa | |

| Nickname(s): Kin la belle (lit. 'Kin the beautiful') | |

Kinshasa on map of DR Congo provinces | |

| Coordinates: 04°19′19″S 15°18′43″E / 4.32194°S 15.31194°E | |

| Country | |

| Founded | 1881 (as Léopoldville) |

| City hall | La Gombe |

| Communes | |

| Government | |

| • Body | Provincial Assembly of Kinshasa |

| • Governor | Daniel Bumba |

| Area | |

• City-province | 9,965 km2 (3,848 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 600 km2 (200 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 240 m (790 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

• City-province | 17,071,000[1] |

| • Density | 1,462/km2 (3,790/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 16,316,000 |

| • Urban density | 27,000/km2 (70,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 17,239,463 |

| • Language | French and Lingala |

| Demonym(s) | Kinshasan Léopoldvillian (1881–1966) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (WAT) |

| Area code | 243 |

| ISO 3166 code | CD-KN |

| License Plate Code | |

| HDI (2019) | 0.577[5] medium1st |

Kinshasa (/kɪnˈʃɑːsə/; French: [kinʃasa]; Lingala: Kinsásá), formerly named Léopoldville until 30 June 1966, is the capital and largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kinshasa is one of the world's fastest-growing megacities, with an estimated population, in 2024, of 17,032,322.[6] It is the most densely populated city in the DRC, the most populous city in Africa, the world's fourth-most-populous capital city, Africa's third-largest metropolitan area, and the leading economic, political, and cultural center of the DRC.[7][8][9][10] Kinshasa houses several industries, including manufacturing,[11] telecommunications,[12][13] banking, and entertainment.[14][15] The city also hosts some of DRC's significant institutional buildings, such as the People's Palace, Palace of the Nation, Court of Cassation, Constitutional Court, African Union City, Marble Palace, Martyrs Stadium, Government House, Kinshasa Financial Center, and other national departments and agencies.[16][17][18][19]

Covering 9,965 square kilometers, Kinshasa stretches along the southern shores of the Pool Malebo, on the Congo River. It forms an expansive crescent across flat, low-lying terrain at an average altitude of about 300 meters.[20] Situated between latitudes 4° and 5° and longitudes East 15° and 16°32, Kinshasa shares its borders with the Mai-Ndombe Province, Kwilu Province, and Kwango Province to the east; the Congo River delineates its western and northern perimeters, constituting a natural border with the Republic of the Congo; to the south lies the Kongo Central Province. Across the river sits Brazzaville, the smaller capital of the neighboring Republic of the Congo, forming the world's second-closest pair of capital cities despite being separated by a four-kilometer-wide unbridged span of the Congo River.[21][22][20][23]

Kinshasa also functions as one of the 26 provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and is administratively divided into 24 communes, which are further subdivided into 365 neighborhoods.[24] With an expansive administrative region, over 90 percent of the province's land remains rural, while urban growth predominantly occurs on its western side.[25] Kinshasa is the largest nominally Francophone urban area globally, with French being the language of government, education, media, public services and high-end commerce, while Lingala is used as a lingua franca in the street. The city's inhabitants are popularly known as Kinois, with the term "Kinshasans" used in English terminology.[7][26][27][28]

The Kinshasa site has been inhabited by Bantus (Teke, Humbu) for centuries and was known as Nshasa before transforming into a commercial hub during the 19th and 20th centuries.[20][29] The city was named Léopoldville by Henry Morton Stanley in honor of Leopold II of Belgium.[20][30][31] The name was changed to Kinshasa in 1966 during Mobutu Sese Seko's Zairianisation campaign as a tribute to Nshasa village.[20]

The National Museum of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is DRC's most prominent and central museum, housing a collection of art, artifacts, historical objects, and modern work of arts. The College of Advanced Studies in Strategy and Defense is the highest military institution in DRC and Central Africa. The National Pedagogical University is DRC's first pedagogical university and one of Africa's top pedagogical universities. N'Djili International Airport is the largest airport in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and ranks 37th in Africa in terms of passengers carried, with 12 international flights per day.[32] In December 2015, Kinshasa was designated as a City of Music by UNESCO and has been a member of the Creative Cities Network since then.[33][34] Nsele Valley Park is the largest urban park in Kinshasa, housing a range of fauna and flora. According to the 2016 annual ranking, Kinshasa is Africa's most expensive city for expatriate employees, ahead of close to 200 global locations.[35][36][37]

Toponymy

[edit]The origin of the name Kinshasa is rooted in multiple theories proposed by scholars. Paul Raymaekers, an anthropologist and ethnologist, suggests that the name derives from the combination of the Kikongo and Kihumbu languages.[20] The prefix "Ki(n)" signifies a hill or inhabited area, while "Nsasa" or "Nshasa" refers to a bag of salt. According to Raymackers, Kinshasa was a significant trading site where people from the Lower Congo (now Kongo Central Province) and South Atlantic Ocean exchanged salt for goods like iron, slaves and ivory brought by those from the Upper Congo (now Tshopo Province).[20] However, Hendrik van Moorsel, an anthropologist, historian and researcher, proposes that Bateke fishermen traded fish for cassava with locals along the riverbank, and the place of this exchange was called "Ulio".[20][29] In Teke, "exchange" is "Utsaya", and "place of exchange" is "Intsaya". Thus, the name evolved from Ulio to Intsaya, and later, under the influence of Kikongo, transformed into Kintsaya, eventually becoming Kinshasa.[20] Kinshasa, also known as N'shasa, is regarded as the primary "place of exchange" on the southern bank of the Pool Malebo, where bartering occurred even before the commercial boom of Kintambo.[20]

The name Nshasa is believed to originate from the Teke verb "tsaya" (tsaa), meaning "to exchange", and the noun "intsaya" (insaa), referring to any market or place of exchange. It was at this location that Teke brokers traded ivory and slaves from the Banunu slave traders, often mistaken for the Yanzi, for European trade items brought by the Zombo and Kongo people.[20] Despite the various theories, the historical name of Kinshasa is known to have been Nshasa, as documented by Henry Morton Stanley during his crossing of Africa from Zanzibar to Boma in 1874–1877 when he mentioned visiting "the king of Nshasa" on 14 March 1877.[20][31][30]

History

[edit]

Prior to the establishment of Kinshasa, the area was for a time part of the Anziku Kingdom. By about 1698, it had become an essentially independent domain known as Nkonkobela.[38]

The city was established as a trading post by Henry Morton Stanley in 1881.[39] It was named Léopoldville in honor of Stanley's employer King Leopold II of the Belgians. He would then proceed to take control of most of the Congo Basin as the Congo Free State, not as a colony but as his private property. The post flourished as the first navigable port on the Congo River above Livingstone Falls, a series of rapids over 300 kilometres (190 miles) below Leopoldville. At first, all goods arriving by sea or being sent by sea had to be carried by porters between Léopoldville and Matadi, the port below the rapids and 150 km (93 mi) from the coast. The completion of the Matadi-Kinshasa portage railway, in 1898, provided an alternative route around the rapids and sparked the rapid development of Léopoldville. In 1914, a pipeline was installed so that crude oil could be transported from Matadi to the upriver steamers in Leopoldville.[40] By 1923, the city was elevated to capital of the Belgian Congo, replacing the town of Boma in the Congo estuary, pursuant to the Royal Decree of 1 July 1923, countersigned by the Minister of the Colonies, Louis Franc.[20][40] Before this, Léopoldville was designated an "urban district", encompassing exclusively the communes of Kintambo and the current Gombe, which burgeoned around Ngaliema Bay.[20][41][42] Then the communes of Kinshasa, Barumbu, and Lingwala emerged. In the 1930s, these communes predominantly housed employees of Chanic, Filtisaf, and Utex Africa.[42]

In 1941, legislative ordinance n°293/AIMO of 25 June 1941, conferred Kinshasa the status of a city and established an Urban Committee (Comité Urbain), with an allocated area of 5,000 hectares and a population of 53,000.[43][42] Concurrently, it became the colony's capital, the Congo-Kasaï Province's capital, and the Moyen Congo district. The city was demarcated into two zones: the urban zone, comprising Léo II, Léo-Ouest, Kalina, Léo-I, or Léo-Est, and Ndolo; and the indigenous zone to the south. The urban populace swelled in 1945 with the cessation of forced labor, facilitating the influx of native Africans from rural regions. Léopoldville then became predominantly inhabited by the Bakongo ethnic group.[42]

In the 1950s, planned urban centers such as Lemba, Matete, and a segment of Ndjili were established to accommodate workers from the Limete industrial zone.[42] Lovanium University, the colony's inaugural university, was founded in 1954.[42] By 1957, Léopoldville comprised eleven communes and six adjunct regions: Kalamu, Dendale (present-day Kasa-Vubu commune), Saint Jean (now Lingwala), Ngiri-Ngiri, Kintambo, Limete, Bandalungwa, Léopoldville (current Gombe), Barumbu, Kinshasa, and Ngaliema; along with the adjunct regions of Lemba, Binza, Makala, Kimwenza, Kimbanseke, and Kingasani. Subsequently, the adjunct regions of Ndjili and Matete were incorporated.[42]

After gaining its independence on 30 June 1960, following riots in 1959, the Republic of the Congo elected its first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba whose perceived pro-Soviet leanings were viewed as a threat by Western interests. This being the height of the Cold War, the U.S. and Belgium did not want to lose control of the strategic wealth of the Congo, in particular its uranium. Less than a year after Lumumba's election, the Belgians and the U.S. bought the support of his Congolese rivals and set in motion the events that culminated in Lumumba's assassination.[44] In 1964, Moïse Tshombe decreed the expulsion of all nationals of Republic of the Congo, Burundi and Mali, as well as all political refugees from Rwanda.[45][46][47][48] In 1965, with the help of the U.S. and Belgium, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu seized power in the Congo. He initiated a policy of "Authenticity", attempting to renativize the names of people and places in the country. On 2 May 1966, the government announced that the nation's major cities would be restored to their pre-colonial names, effective on 30 June, the sixth anniversary of independence.[49] Léopoldville was renamed Kinshasa, for a village named Kinshasa that once stood near the site. Kinshasa grew rapidly under Mobutu, drawing people from across the country who came in search of their fortunes or to escape ethnic strife elsewhere, thus adding to the many ethnicities and languages already found there.

In 1991 the city had to fend off rioting soldiers, who were protesting the government's failure to pay them. Subsequently a rebel uprising began, which in 1997 finally brought down the regime of Mobutu.[40] Kinshasa suffered greatly from Mobutu's excesses, mass corruption, nepotism and the civil war that led to his downfall. Nevertheless, it is still a major cultural and intellectual center for Central Africa, with a flourishing community of musicians and artists. It is also the country's major industrial center, processing many of the natural products brought from the interior.

Joseph Kabila, president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 2001 to 2019, was not overly popular in Kinshasa.[50] Violence broke out following the announcement of Kabila's victory in the contested election of 2006; the European Union deployed troops (EUFOR RD Congo) to join the UN force in the city. The announcement in 2016 that a new election would be delayed two years led to large protests in September and December which involved barricades in the streets and left dozens of people dead. Schools and businesses were closed down.[51][52]

Geography

[edit]

Location

[edit]Kinshasa is strategically situated on the southern bank of the expansive Malebo Pool, spanning 9,965 square kilometers, configured in a grand crescent shape atop a low-lying, flat terrain with an average elevation hovering around 300 meters.[53][54] Positioned between latitudes 4° and 5° and longitudinal coordinates 15° to 16°32 east, Kinshasa is flanked by the provinces of Mai-Ndombe, Kwilu, and Kwango to the east, while the Congo River delineates its western and northern boundaries, naturally demarcating the border with the Republic of the Congo. To the south, it is demarcated by the Kongo Central Province.[55]

The Congo River is the second longest river in Africa after the Nile and has the continent's greatest discharge. As a waterway it provides a means of transport for much of the Congo Basin; it is navigable for river barges between Kinshasa and Kisangani; many of its tributaries are also navigable. The river is an important source of hydroelectric power, and downstream from Kinshasa it has the potential to generate power equivalent to the usage of roughly half of Africa's population.[56]

Relief

[edit]Topographically, Kinshasa has a marshy, alluvial plain, with altitudes ranging from 275 to 300 meters, along with hilly terrain that elevates from 310 to 370 meters.[57][55][58] The city has four principal features: the Malebo Pool, a vast expanse of water with islands and islets; the Kinshasa Plain, which is a highly urbanizable space, but susceptible to drainage issues; the Terrace, which is a series of low ridges overlooking the plain; and the Hills Area, which is characterized by deep valleys and cirque-shaped formations.[55]

The Malebo Pool spans over 35 kilometers in length and 25 kilometers in width and is encircled by Ngaliema Municipality to the west and Maluku Municipality to the east, traversing through Gombe, Barumbu, Limete, Masina, and Nsele municipalities.[55] The Kinshasa Plain has a banana-like shape and is surrounded by eastward-oriented hills. Its low sandy alluvial masses extend from Maluku Municipality in the east to the western foothills of Ngaliema, covering approximately 20,000 hectares.[55]

The Terrace is mainly situated in the city's western expanse, between N'djili and Mount Ngafula. It comprises stony blocks of soft sandstone and silica-covered yellow clay, topped with brown silt, and ranges from 10 to 25 meters in height. It retains vestiges of an ancient surface.[55] The Hills Area commences several kilometers from the Malebo Pool and is characterized by deep valleys and cirque-shaped formations. These hills reach heights surpassing 700 meters and exhibit gentle, rounded contours sculpted by local rivers.[55] While their eastern counterparts may reflect remnants of the Batéké Plateau, their origins in the west and south remain enigmatic. Their natural erosion processes are exacerbated by human intervention, sometimes assuming catastrophic proportions.[55]

Hydrography

[edit]

Kinshasa's hydrographic network encompasses the Congo River and its principal left bank tributaries, traversing the city from south to north. These include the Lukunga, Ndjili, Nsele, Bombo, or Mai-Ndombe rivers and the Mbale.[55][59][60] Unfortunately, these waterways are polluted due to the city's demographic pressures and inadequate sanitation.[55]

Geology

[edit]Geologically, the soil in Kinshasa is of the Arenoferrasol category,[61][62] characterized by fine sands with a clay content typically below 20%, low organic matter, and absorbent complex saturation.[55] The basement is composed of Precambrian bedrock, featuring finely stratified red sandstone often infused with feldspar. This rock is visible at the rapids' base near Mount Ngaliema and south of the N'djili River, and effectively withstands erosive forces.[55]

Vegetation

[edit]

Kinshasa's vegetation comprises gallery forests, grassy formations, ruderal plant groups, and aquatic formations. These gallery forests, found along the main watercourses within humid valleys of the Congolese guinéo ombrophile type, have degraded into highly exploited pre-forest fallows, manifesting as reclusive foresters of varying ages.[55] Ruderal plant groups line railway tracks within narrow strips, reflecting the region's vegetation cover's discontinuity and repetition. Kinshasa is home to diverse vegetation types, each intricately linked to specific ecological parameters.[55]

Residential and commercial areas

[edit]Kinshasa is a city of sharp contrasts, with affluent residential and commercial areas and three universities alongside sprawling slums.[63] The older and wealthier part of the city (ville basse) is located on a flat area of alluvial sand and clay near the river, while many newer areas are found on the eroding red soil of surrounding hills.[2][50] Older parts of the city were laid out on a geometric pattern, with de facto racial segregation becoming de jure in 1929 as the European and African neighborhoods grew closer together. City plans of the 1920s–1950s featured a cordon sanitaire or buffer between the white and black neighborhoods, which included the central market as well as parks and gardens for Europeans.[64]

Urban planning in post-independence Kinshasa has been limited. The Mission Française d'Urbanisme drew up some plans in the 1960s which envisioned a greater role for automobile transportation but did not predict the city's significant population growth. Thus much of the urban structure has developed without guidance from a master plan. According to UN-Habitat, the city is expanding by eight square kilometers per year. It describes many of the new neighborhoods as slums, built in unsafe conditions with inadequate infrastructure.[65] Nevertheless, spontaneously developed areas have in many cases extended the grid street plan of the original city.[63]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Kinshasa is both a city (ville in French) and a province, one of the 26 provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nevertheless, it has city subdivisions and is divided into 24 communes (municipalities), which in turn are divided into 369 quarters and 21 embedded groupings.[66] Maluku, the rural commune to the east of the urban area, accounts for 79% of the 9,965 km2 (3,848 sq mi) total land area of the city-province,[25] with a population of 200,000–300,000.[63] The communes are grouped into four districts which are not in themselves administrative divisions.

| ||

|

Abbreviations : Kal. (Kalamu), Kin. (Kinshasa), K.-V. (Kasa-Vubu), Ling. (Lingwala), Ng.-Ng. (Ngiri-Ngiri)

|

Climate

[edit]Under the Köppen climate classification, Kinshasa has a tropical wet and dry climate (Aw). Its lengthy rainy season spans from October through May, with a relatively short dry season, between June and September. Kinshasa lies south of the equator, so its dry season begins around its winter solstice, which is in June. This is in contrast to African cities further north featuring this climate where the dry season typically begins around December. Kinshasa's dry season is slightly cooler than its wet season, though temperatures remain relatively constant throughout the year.

| Climate data for Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36 (97) |

36 (97) |

38 (100) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

32 (90) |

33 (91) |

35 (95) |

35 (95) |

37 (99) |

34 (93) |

38 (100) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.6 (87.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.1 (88.0) |

28.8 (83.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.9 (84.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.9 (78.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

23.7 (74.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

20 (68) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

18 (64) |

15 (59) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

16 (61) |

17 (63) |

18 (64) |

16 (61) |

10 (50) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 163 (6.4) |

165 (6.5) |

221 (8.7) |

238 (9.4) |

142 (5.6) |

9 (0.4) |

5 (0.2) |

2 (0.1) |

49 (1.9) |

98 (3.9) |

247 (9.7) |

143 (5.6) |

1,482 (58.4) |

| Average precipitation days | 12 | 12 | 14 | 17 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 14 | 115 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 82 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 79 | 74 | 74 | 79 | 83 | 83 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 136 | 141 | 164 | 153 | 164 | 144 | 133 | 155 | 138 | 149 | 135 | 127 | 1,739 |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org (temperature)[67] Weatherbase (extremes)[68] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute (precipitation, sun, and humidity)[69] | |||||||||||||

Parks and gardens

[edit]Kinshasa is home to a diverse range of parks and gardens:

- Nsele Valley Park, the largest urban park in the city situated along the Nsele River, offers a setting for outdoor activities. It features picnic areas, walking trails, and viewpoints overlooking the river.[70]

- Parc Présidentiel, situated along the Congo River, is a park in Kinshasa. The park offers ponds, pools, and fountains, while the Théâtre de Verdure serve as venues for cultural performances. The park's mini zoo has a diverse array of animals.

- Jardin Zoologique, located in the heart of Gombe commune, is a zoo in Kinshasa. The zoo houses a wide variety of mammals, reptiles, and birds, offering an educational and entertaining experience.[71]

- Jardin Botanique de Kinshasa, situated in Gombe, is a botanical garden that showcases the city's botanical treasures. The botanical garden houses an array of plants and colorful flowers.[72]

- Lola ya Bonobo, located south of Kinshasa, is the world's only sanctuary for orphaned bonobos. Situated at the Petites Chutes de la Lukaya, it provides a safe and nurturing environment for endangered primates.[73]

Demographics

[edit]

An official census conducted in 1984 counted 2.6 million residents.[74] Since then, all estimates are extrapolations. The estimates for 2005 fell in a range between 5.3 million and 7.3 million.[63] In 2017, the most recent population estimate for the city, it has a population of 11,855,000.[75]

According to UN-Habitat, 390,000 people immigrate to Kinshasa annually, fleeing warfare and seeking economic opportunity.[76]

According to a projection (2016) the population of metropolitan Kinshasa will increase significantly, to 35 million by 2050, 58 million by 2075 and 83 million by 2100,[77] making it one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world.

Language

[edit]The official language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, of which Kinshasa is the capital, is French (See: Kinshasa French vocabulary). Kinshasa is the largest officially Francophone city in the world, albeit that the vast majority of people either cannot speak French, or struggle in speaking it.[78][79][80] Although Lingala is widely used as a spoken language, French is the language of street signs, posters, newspapers, government documents, schools; it dominates plays, television, and the press, and it is used in vertical relationships among people of different social classes. People of the same class, however, speak the Congolese languages (Kikongo, Lingala, Tshiluba or Swahili) among themselves.[81] Kinshasa hosted the 14th Francophonie Summit in October 2012.[82]

Government and politics

[edit]

The head of Kinshasa ville-province has the title of Gouverneur. Daniel Bumba has been governor since 21 June 2024.[83] Each commune has its own Bourgmestre.[63]

Although political power in the DRC is fragmented, Kinshasa as the national capital represents the official center of sovereignty, and thus of access to international organizations and financing, and of political powers such as the right to issue passports.[50] Kinshasa is also the primate city of the DRC with a population several times larger than the next-largest city, Lubumbashi.[84][65]

The United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, known by its French acronym MONUSCO (formerly MONUC) has its headquarters in Kinshasa. In 2016, the UN placed more peacekeepers on active duty in Kinshasa in response to the unrest directed against Kabila, at that time.[85] Critics, including recently[when?] the US ambassador to the UN,[86] have accused the peacekeeping mission of supporting a corrupt government.[87][88]

Other non-governmental organizations play significant roles in local governance.[89] Since 2016, the Belgian development agency (Coopération technique belge; CTB) has sponsored the Programme d'Appui aux Initiatives de Développement Communautaire (Paideco), a 6-million-euro program aimed at economic development. It began work in Kimbanseke, a hill commune with population verging on one million.[90]

Economy

[edit]

Mining sector and export growth

[edit]In 2022, Kinshasa's GDP exceeded initial expectations by expanding 8.5%, as reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The mining industry in the DRC has been instrumental in maintaining a positive economic outlook, even amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Raw material exports, particularly cobalt and copper, have experienced historically high prices, resulting in substantial investment in the industry. Parenthetically, production has increased, and Covid-related restrictions have eased, leading to sustained economic growth.[91][92]

Fiscal performance and debt sustainability

[edit]Despite facing external challenges, including the repercussions of the Russo-Ukrainian War, the DRC has shown fiscal stability. In 2022, tax performance exceeded projections, showcasing improved revenue generation. However, increased expenditures related to security concerns and internal arrears resulted in a deterioration of the overall budget balance. Nevertheless, the DRC's debt risk remains moderate, with public debt at 24.7% of GDP. The approval of the third review of the IMF program reflects the satisfactory performance of the country's reform efforts.[93][92]

Companies, foreign exchange reserves, international support

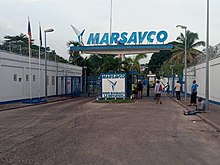

[edit]Big manufacturing companies such as Marsavco S.A., All Pack Industries and Angel Cosmetics are located in the center of town (Gombe) in Kinshasa.

There are many other industries, such as Trust Merchant Bank, located in the heart of the city. Food processing is a major industry, and construction and other service industries also play a significant role in the economy.[94]

Although home to only 13% of the DRC's population, Kinshasa accounts for 85% of the Congolese economy as measured by gross domestic product.[65] A 2004 investigation found 70% of inhabitants employed informally, 17% in the public sector, 9% in the formal private sector, and 3% other, of a total 976,000 workers. Most new jobs are classified as informal.[63] By the end of 2022, Kinshasa's foreign exchange reserves had seen a significant improvement, soaring past $4.5 billion. The DRC benefits from support and partnerships with several global organizations and financial institutions, including the IMF, World Bank, African Development Bank, European Union, China and France.[93]

The People's Republic of China has been heavily involved in the Congo since the 1970s, when they financed the construction of the Palais du Peuple and backed the government against rebels in the Shaba war. In 2007–2008 China and Congo signed an agreement for an $8.5 billion loan for infrastructure development.[95] Chinese entrepreneurs are gaining an increasing share of local marketplaces in Kinshasa, displacing in the process formerly successful Congolese, West African, Indian, and Lebanese merchants.[96]

Mean household spending in 2005 was the equivalent of US$2,150, amounting to $1 per day per person. The median household spending was $1,555, 66 cents per person per day. Among the poor, more than half of this spending goes to food, especially bread and cereal.[63]

Education

[edit]

Kinshasa is home to several education institutes, covering a wide range of disciplines, including civil engineering, nursing, and journalism. The city is also home to three large universities and an arts school:

- Académie de Design (AD)

- Institut Supérieur d'Architecture et Urbanisme

- Pan-African University of the Congo

- University of Kinshasa

- Université Libre de Kinshasa

- Université catholique du Congo

- Congo Protestant University

- Université Chretienne de Kinshasa

- National Pedagogy University

- National Institute of Arts

- Institut Supérieur de Publicité et Médias

- Centre for Health Training (CEFA)[97]

Primary and secondary schools:

- Lycée Prince de Liège (primary and secondary education, French Community of Belgium curriculum)

- Prins van Luikschool Kinshasa (primary education, Flanders curriculum)[98]

- Lycée Français René Descartes (primary and secondary education, French curriculum)

- The American School of Kinshasa

- Allhadeff School[99]

The education system in DRC is plagued by low coverage, low quality and poor educational infrastructure, especially in rural areas. According to USAID (2018), 3.5 million children of primary school age are out of school, and 44% of those who do attend school started only after age six. Various statistical estimates by UNESCO, (2013) regarding secondary and tertiary education also reveal the difficulties facing the country. In DRC it is difficult to get a reliable estimate on the actual proportion of the population who can read and write, however, according to data from UIS (2016), the literacy rate of the population of 15 years and older in the country, is estimated to 77.04%. This rate is 88.5% for men and 66.5% for women. There is also a shortage of reading material, and certainly no culture of reading for pleasure. [100]

Health and medicine

[edit]

There are twenty hospitals in Kinshasa, plus various medical centers and polyclinics.[101]

Culture

[edit]

Located in Kinshasa are the National Museum and the Kinshasa Fine Arts Academy.[102]

Kinshasa has a flourishing music scene which, since the 1960s, has operated under the patronage of the city's elite.[50] The Orchestre Symphonique Kimbanguiste, formed in 1994, began using improved musical instruments and has since grown in means and reputation.[103]

A pop culture ideal type in Kinshasa is the mikiliste, a fashionable person with money who has traveled to Europe. Adrien Mombele, a.k.a. Stervos Niarcos, and musician Papa Wemba were early exemplars of the mikiliste style.[50] La Sape, a linked cultural trend also described as dandyism, involves wearing flamboyant clothing.[104]

Many Kinois have a negative view of the city, expressing nostalgia for the rural way of life, and a stronger association with the Congolese nation than with Kinshasa.[105]

Places of worship

[edit]-

Église Sainte-Anne de Kinshasa (Catholic Church in the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

-

Église Francophone CBCO Kintambo (Baptist Community of Congo)

-

Eglise Saint Léopold à Ngaliema, Kinshasa

Among the places of worship, which are predominantly Christian churches and temples: Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Kinshasa (Catholic Church), Kimbanguist Church, Baptist Community of Congo (Baptist World Alliance), Baptist Community of the Congo River (Baptist World Alliance), The Salvation Army, Assemblies of God, Province of the Anglican Church of the Congo (Anglican Communion), The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints which has a temple and over 100 congregations in Kinshasa, Presbyterian Community in Congo (World Communion of Reformed Churches).[106] There are also Muslim mosques. A Baha'i House of Worship is in construction.[107] A Jewish synagogue, operated by the Chabad world movement, exists.[4]

Media

[edit]

Press freedom is very low in the DRC, especially in Kinshasa. State run channels report little political news. Journalism is strictly controlled, with DRC scoring only 48.55% on the Press Freedom Index, in 2023.[108] Nevertheless, Kinshasa is home to several media outlets, including radio and television stations, including state-run Radio-Télévision nationale congolaise (RTNC) and privately run Digital Congo and Raga TV.

Several national radio stations, including La Voix du Congo, which is operated by RTNC, UN-backed Radio Okapi are based in Kinshasa, as well as numerous local stations. The BBC is also available in Kinshasa on 92.6 FM.[109]

The state-controlled Agence Congolaise de Presse news agency is based in Kinshasa, as well as several daily and weekly newspapers and news websites, including L'Avenir (daily), La Conscience, LeCongolais (online),L'Observateur (daily), Le Phare, Le Potentiel, and Le Soft.[110]

Most of the media use French and Lingala to a large extent; very few use the other national languages.

Sports

[edit]Sports, especially football and martial arts are popular in Kinshasa. The city is home to the country's national stadium, the Stade des Martyrs (Stadium of the Martyrs). The Vita Club, Daring Club Motema Pembe and AS Dragons frequently draws large crowds, enthusiastic and sometimes rowdy, to the Stade des Martyrs. Dojos are popular and their owners influential.[50]

In 1974, Kinshasa hosted The Rumble in the Jungle boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, in which Ali defeated Foreman, to regain the World Heavyweight title.

Buildings and institutions

[edit]

Kinshasa is home to the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo including:

- the Palais de la Nation, home of the President, in Gombe;

- the Palais du Peuple, meeting place of both houses of Parliament, Senate and National Assembly, in Lingwala;

- the Palais de Justice, in Gombe;

- the Cité de l'OUA, built for the Organization of African Unity in the 1970s and now serving government functions, in Ngaliema.

The Central Bank of the Congo has its headquarters on Boulevard Colonel Tshatshi, across the street from the Mausoleum of Laurent Kabila and the presidential palace.

Notable features of the city include the Gecamines Commercial Building (formerly SOZACOM) and Hotel Memling; L'ONATRA, the building of the Ministry of Transport; the central market; the Limete Tower.

Infrastructure and housing

[edit]

The city's infrastructure for running water and electricity is generally in bad shape.[111] The electrical network is in disrepair to the extent that prolonged and periodic blackouts are normal, and exposed lines sometimes electrify pools of rainwater.[50][63]

Regideso, the national public company with primary responsibility for water supply in the Congo, serves Kinshasa only incompletely, and without uniform quality. Other areas are served by decentralized Associations des Usagers des Réseau d'Eau Potable (ASUREPs).[74] Gombe uses water at a high rate (306 liters per day per inhabitant) compared to other communes (from 71 L/d/i in Kintambo down to 2 L/d/i in Kimbanseke).[63]

The city is estimated to produce 6,300 m3 of trash and 1,300 m3 of industrial waste per day, with little to no capacity for disposal.[63]

The housing market has seen rising prices and rents since the 1980s. Houses and apartments in the central area are expensive, with houses selling for a million dollars and apartments going for $5000 per month. High prices have spread outward from the central area as owners and renters move out of the most expensive part of the city. Gated communities and shopping malls, built with foreign capital and technical expertise, began to appear in 2006. Urban renewal projects have led in some cases to violent conflict and displacement.[50][112] The high prices leave incoming refugees with few options for settlement besides illegal shantytowns such as Pakadjuma.[76]

In 2005, 55% of households had televisions and 43% had mobile phones. 11% had refrigerators and 5% had cars.[63]

Transport

[edit]

The city-province has 5000 km of roadways, 10% of which are paved. The Boulevard du 30 Juin (Boulevard of 30 June) links the main areas of the central district of the city. Other roads also converge on Gombe. The east–west road network linking the more distant neighborhoods is weak and thus transit through much of the city is difficult.[63] The quality of roads has improved somewhat, developed in part with loans from China, since 2000.[50]

The public bus company for Kinshasa, created in 2003, is Transco (Transport au Congo).[113]

Several companies operate registered taxis and taxi-buses, identifiable by their yellow color. In addition, an Uber-style, mobile phone, app-based, taxi hailing service was introduced in 2023.[114]

Air

[edit]The city has two airports: N'djili Airport (FIH) is the main airport with connections to other African countries as well as to Istanbul, Brussels, Paris and some other destinations. N'Dolo Airport, located close to downtown, is used for domestic flights only with small turboprop aircraft. Several international airlines serve Ndjili Airport including Kenya Airways, South African Airways, Ethiopian Airlines, Brussels Airlines, Air France and Turkish Airlines. An average of ten international flights depart each day from N'djili Airport.[115] A small number of airlines provide domestic service from Kinshasa, for example Congo Airways and CAA. Both offer scheduled flights from Kinshasa to a limited number of cities inside DR Congo.[116]

Rail

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

This section needs to be updated. (November 2022) |

The Matadi–Kinshasa Railway[117] connects Kinshasa with Matadi, Congo's Atlantic port. The line reopened in September 2015 after around a decade without regular service. There is an intermittent service, with a poor safety record.

According to the Société Commerciale des Transports et des Ports (SCTP), the Matadi-Kinshasa Railway (CFMK) has the highest transport of goods in import, 8 746 tonnes in January, 11,318 tonnes in February 10,032 tonnes in March, 7,244 tonnes in April, 5,024 tonnes in March and 7,745 tonnes in June. The monthly tonnage of exported goods reached only 1,000 tonnes in the month of March 2018. In January some 284 tonnes of goods were exported from the ports of Boma and Matadi, via the railway, and 711 tonnes in February, then 1,058 tonnes in March, 684 tonnes in April, 818 tonnes in May and 853 tonnes in June.

The monthly statistics for passenger traffic are as follows: 2,294 persons in January, 1,836 in February, 2065 in March, 2,660 in April, 1,952 in May and 2,660 in June.

The line connecting the port of Matadi to Kinshasa is 366 km long. Its distance has been since 3111 of 3112 feet or 42 inches (lane capped 1,067 meter): This railway belongs, in fact, to the National Railway Company of the Congo (Société nationale des chemins de fer du Congo; SNCC). It is only exploited by the SCTP, formerly ONATRA, according to an agreement signed by the two companies.

This line lost large shares of the market, following its lamentable state, insecurity on the rails (some trains are attacked), and the rehabilitation of the road along the rails in 2000. According to Congolese sources, an agreement with a Chinese construction company was signed in 2006, according to which this Chinese company will finance the renovation of the track, the rolling stock, the communication channels for the signaling, and the electrical power source. The ex-ONATRA has, in fact, opted for an aggressive commercial policy to revive the rails.

On June 30, 2018, the SCTP received two locomotives and 50 wagons from the African firm ARSS (African-Rolling Stock Solution).

In 2017, some 2.2 million tonnes of cement were produced by the two new start-up companies, PPC Barnet and Kongo Cement Factory (CIMKO). The SCTP did indeed transport part of this production to Kinshasa but the exact quantity was not communicated by the railway department of the company, the former DG Kimbembe Mazunga had communicated an agreed protocol of agreements with the cement manufacturers of Kongo-Central for the transport of their productions.

External transport

[edit]Kinshasa is the major river port of the Congo. The port, called 'Le Beach Ngobila' extends for about 7 km (4 mi) along the river, comprising scores of quays and jetties with hundreds of boats and barges tied up. Ferries cross the river to Brazzaville, a distance of about 4 km (2 mi). River transport also connects to dozens of ports upstream, such as Kisangani and Bangui.

There are road and rail links to Matadi, the sea port in the Congo estuary 150 km (93 mi) from the Atlantic Ocean.

There are no rail links from Kinshasa further inland, and road connections to much of the rest of the country are few and in poor condition, although there has been a road built to the city of Kikwit (around 500 km away) that has been in operation since 2015 or so. It was recently extended to the small city of Tshikapa.

Social issues

[edit]

Crime and punishment

[edit]Since the Second Congo War, the city has been striving to recover from disorder, with many youth gangs living and operating from Kinshasa's poorer areas.[118] The U.S. State Department in 2010 informed travelers that Kinshasa and other major Congolese cities are generally safe for daytime travel, but to beware of robbers, especially in traffic jams and in areas near hotels and stores.[119]

Some sources say that Kinshasa is extremely dangerous, with one source giving a homicide rate of 112 per 100,000 people per year.[120] Another source cites a homicide rate of 12.3 per 100,000.[121] By some accounts, crime in Kinshasa is not so rampant, due to relatively good relations among residents and perhaps to the severity with which even petty crime is punished.[50]

While the military and National Police operate their own jails in Kinshasa, the main detention facility under the jurisdiction of the local courts is the Kinshasa Penitentiary and Re-education center in Makala. This prison houses much more than its nominal capacity of 1,000 inmates. In 2024, the population of Makala Prison was reported at 15,000.[122] The Congolese military intelligence organization, Détection Militaire des Activités Anti-Patrie (DEMIAP) operates the Ouagadougou prison in Kintambo commune with notorious cruelty.[121][123]

Street children

[edit]In the 2010s, street children or "Shegués", often orphaned, are subject to abuse by the police and military.[124] Of the estimated 20,000 children living on Kinshasa's streets, almost a quarter are beggars, some are street vendors and about a third have some kind of employment.[125] Some have fled from physically abusive families, notably step-parents, others were expelled from their families as they were believed to be witches,[126] and have become outcasts.[127][128][129]

Street children are mainly boys,[130] but the percentage of girls is increasing according to UNICEF. Ndako ya Biso provides support for street children, including overnight accommodation for girls.[131] There are also second generation street children.[132]

These children have been the object of considerable outside study.[133]

Notable people

[edit]International relations

[edit]Kinshasa is twinned with:

Brazzaville, Republic of Congo

Brazzaville, Republic of Congo Brussels, Belgium[134]

Brussels, Belgium[134] Johannesburg, South Africa

Johannesburg, South Africa

In popular culture

[edit]With its mix of culture, history, and lively atmosphere, Kinshasa has become a focus for filmmakers, musicians, writers, and artists.[136]

Cinematic and TV representations

[edit]

Kinshasa has been represented in various films, most notably in the film When We Were Kings (1996). This documentary chronicles the historic Rumble in the Jungle boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, held in Kinshasa in 1974. The film showcases the electrifying atmosphere of the city during the momentous event.[137][138][139]

In Viva Riva! (2010), directed by Djo Tunda Wa Munga, the film offers a gritty portrayal of the city's underworld, showing the tension between corruption, ambition, and survival.[140]

Kinshasa's social complexities are explored in Félicité (2017), directed by Alain Gomis. The film explores themes of pliability, community, and the power of music in the face of adversity. The film portrayed the essence of Kinshasa, depicting its vivacious music scene and the struggles faced by its inhabitants with sensitivity and authenticity.[141]

In 2019, The Widow (TV series) was released on Amazon Prime and the UK's ITV network. The mini-series tells the story of a woman searching for her husband in Kinshasa, after believing he'd been killed in a plane crash.[142]

Literary depictions

[edit]Throughout history, authors have depicted the essence of Kinshasa in their writing, delving into its diverse cultural fabric, storied past, and the personal narratives of its residents. Fiston Mwanza Mujila's Tram 83 depicts the city's nightlife while exploring themes of postcolonial identity and the struggle for social and economic progress.[143] Meanwhile, In Koli Jean Bofane's novel Congo Inc.: Bismarck's Testament the city serves as a microcosm of post-colonial Congo, exploring themes of globalization, political corruption, and environmental degradation.[144]

Music and dance

[edit]

The music scene of Kinshasa has also made a significant impact on popular culture. Congolese rumba, a genre born in the city during the 1930s, continues to resonate globally. Artists like Franco Luambo Makiadi, Syran Mbenza, Le Grand Kallé, Nico Kasanda, Tabu Ley Rochereau, M'bilia Bel, Madilu System, Papa Noël Nedule, Vicky Longomba, Awilo Longomba, Pépé Kallé, Kanda Bongo Man, Nyboma Mwan'dido, General Defao, Papa Wemba, Koffi Olomide, Werrason, Abeti Masikini, Lokua Kanza, Fally Ipupa, and Ferré Gola have played a key role in popularizing Congolese music on the international stage, infusing their compositions with Kinshasa's pulsating rhythms and infectious energy. The infectious beats of Congolese music have influenced artists across continents, shaping genres like soukous and influencing international musicians such as Paul Simon and Vampire Weekend.[145][146][147][148]

Visual arts and fashion

[edit]Kinshasa's street art scene has gained recognition globally, with talented artists using their creations to express social and political messages. Murals and graffiti, adorned with colorful imagery, can be found throughout the city.[149][150][151]

La Sape

[edit]

The La Sape subculture, characterized by extravagant and dapper fashion choices, has become an emblem of style, self-expression, and identity for the sapeurs of Kinshasa. It has gained international recognition through the lens of well-known photographers such as Daniele Tamagni. Tamagni's book Gentlemen of Bacongo (2009) showcases the impeccable style and distinct personalities of Kinshasa's sapeurs, accentuating their taste in tailored suits, bold hues, and eye-catching accessories.[152][153] The city serves as the epicenter of La Sape, with various neighborhoods, communes and districts hosting events like le concours or la fête where sapeurs can display their style. La Sape has also inspired popular music and cultural expressions in Kinshasa, with sapeurs often featured in Congolese music videos as symbols of refinement and sophistication. Musicians such as Papa Wemba have embraced La Sape as an essential part of their artistic identity.[152][154][155]

Martial arts

[edit]WWE wrestler Shinsuke Nakamura uses a running knee strike, called the Kinshasa, as his finisher, a reference to the eponymous city. The move was previously named as Bomaye (which translated to "kill him") during his time in New Japan Pro Wrestling but was renamed in 2016 when he was signed with the WWE for trademark reasons.[156] Both Bomaye and Kinshasa are homages to Nakamura's mentor, Antonio Inoki, who received Bomaye as a nickname from Muhammad Ali when Inoki and Ali fought in 1976, with Ali first hearing Bomaye in Kinshasa during the Rumble In The Jungle.[156]

See also

[edit]Films about Kinshasa

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Institut National De La Statistique. "Projections demographiques 2019–25 (in French)". Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ a b Matthieu Kayembe Wa Kayembe, Mathieu De Maeyer et Eléonore Wolff, "Cartographie de la croissance urbaine de Kinshasa (R.D. Congo) entre 1995 et 2005 par télédétection satellitaire à haute résolution Archived 17 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine", Belgeo 3–4, 2009; doi:10.4000/belgeo.7349.

- ^ "DemographiaWorld Urban Areas – 13th Annual Edition" (PDF). Demographia. April 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ "PopulationStat.com". Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Kinshasa Population 2024, World population review 30 May 2024

- ^ a b Cécile B. Vigouroux & Salikoko S. Mufwene (2008). Globalization and Language Vitality: Perspectives from Africa, pp. 103 & 109. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826495150. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Chignac, François (6 July 2023). "Conférence Risque Pays 2023 : le climat des affaires s'améliore en RDC". euronews (in French). Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Rouaud, Pierre Olivier (25 July 2022). "RD Congo: les fortes prévisions de croissance confortées par le FMI". Classe-export.com (in French). Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Kaseso, Joel Machozi (27 May 2023). "Faux, le magazine Forbes n'a pas publié un classement du "Top 10 des meilleurs villes de la RDC en 2023"". Congocheck.net (in French). Archived from the original on 30 December 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Congo-Kinshasa: Les industries manufacturières affichent une bonne croissance". AllAfrica (in French). 13 September 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Syosyo, Crispin Malingumu (2015). "Analyse du marché des télécommunications mobiles en République Démocratique du Congo: Dynamique du marché et stratégies des acteurs". hal.science (in French). Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Tuema, Jacques Kiambu Di (5 December 2009). "Déréglementation des services de télécommunications en République Démocratique du Congo et inégale répartition des ressources". Revue d'Économie Régionale & Urbaine (in French) (2009/5): 975–994. doi:10.3917/reru.095.0975. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "La culture et le divertissement au Congo". Actualite.cd (in French). 27 May 2021. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Luzonzo, Merseign (2016). "Les fondements de l'émergence économique de la République Démocratique du Congo: défis et perspectives" [The foundations of the economic emergence of the Democratic Republic of Congo: challenges and prospects] (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Université Catholique du Congo. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ "Actualité | Quelle est la nature juridique de l'autorité du ministre de la Justice sur le Parquet ?". www.mediacongo.net (in French). Kinshasa. 6 July 2020. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "En RDC, le difficile accès à la justice pour les femmes victimes de viols". RFI (in French). 25 November 2020. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Rédaction, La (28 January 2019). "Félix Tshisekedi s'installe dans "une modeste" villa à la cité de l'UA". Politico.cd (in French). Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Huband, Mark (20 May 2019). The Skull Beneath The Skin: Africa After The Cold War. Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-429-96439-8. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kinyamba, S. Shomba; Nsenda, F. Mukoka; Nonga, D. Olela; Kaminar, T.M.; Mbalanda, W. . (2015). "Monographie de la ville de Kinshasa" (PDF) (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Institut Congolais de Recherche en Développement et Etudes Stratégiques (ICREDES). pp. 9–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ Buron, Thierry (22 November 2020). "Brazzaville et Kinshasa : proches, mais séparées". Conflits : Revue de Géopolitique (in French). Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Academie, Jan Van Eyck (12 June 2006). Brakin: Brazzaville-Kinshasa : Visualizing the Visible. Baden, Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers. ISBN 978-3-03778-076-3. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Burke, Jason (17 January 2017). "Face-off over the Congo: the long rivalry between Kinshasa and Brazzaville". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ Zimi, Gutu Kia (10 January 2021). Growing Trees in Urban Kinshasa: Shrub Vegetation in Residential Plots in Kinshasa. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthoHouse. ISBN 978-1-6655-1262-6. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Géographie de Kinshasa". Ville de Kinshasa. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Magnan, Pierre (2 June 2017). "Kinshasa a dépassé Paris comme plus grande ville francophone du monde". Franceinfo (in French). Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "This is the most French-speaking city in the world". En-vols.com. 10 October 2022. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Cornall, Flo (1 June 2023). "Congolese artists wear costumes made of trash to shine a light on Kinshasa's pollution problem". CNN. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ a b Moorsel, Hendrik van (1968). Atlas de préhistoire de la plaine de Kinshasa (in French). Kinshasa, Belgian Congo: Université Lovanium.

- ^ a b Ness, Immanuel (19 September 2017). Encyclopedia of World Cities. Thames, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317471585. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ a b Boya, Loso Kiteti (2010). D.R. Congo. Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris Corporation. p. 175. ISBN 9781450082495. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ [Airport rankings: Africa https://gettocenter.com/airports/continent/africa Archived 16 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine]

- ^ "Kinshasa: Ville Créative de la Musique" [Kinshasa: Creative City of Music] (PDF). en.unesco.org (in French). Paris, France. 2016–2019. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "Kinshasa: About the Creative City". En.unesco.org. 2015. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Velluet, Quentin (31 October 2018). "Offres d'emploi : les meilleures opportunités en Afrique – Jeune Afrique". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Karuri, Ken (22 June 2016). "Luanda, Kinshasa ranked among world's most expensive cities for expats". Africanews. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Hughes, Martin (3 July 2016). "Kinshasa Is Most Expensive City To Live For Expats". Money International. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ John K. Thornton. History of West Central Africa. Cambridge University Press, 2020. p. 208

- ^ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 144

- ^ a b c "Kinshasa – national capital, Democratic Republic of the Congo". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Moulin, Léon de Saint (1971). Les anciens villages des environs de Kinshasa (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Université Lovanium. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Luaka, Evrard Nkenku (2005). "La gestion et la gouvernance des déchets dans la ville-province de Kinshasa" [Waste management and governance in the city-province of Kinshasa] (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: University of Kinshasa. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Kinyamb, S. Shomba; Nsenda, F. Mukoka; Nonga, D. Olela; Kaminar, T.M.; Mbalanda, W. (2015). "Monographie de la ville de Kinshasa" [Monograph of the city of Kinshasa] (PDF) (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Institut Congolais de Recherche en Développement et Etudes Stratégiques (ICREDES). p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja (17 January 2011). "Patrice Lumumba: the most important assassination of the 20th century". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ Jules Gerard-Libois and Benoit Verhaegen, Congo 1964: Political Documents of a Developing Nation, Princeton University Press, 2015, p. 450

- ^ "Congo Starts Expulsions". The New York Times. 22 August 1964. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Daouda Gary-Tounkara, 1964 : le Mali réinsère ses ressortissants expulsés, In: Plein droit 2016/1 (n° 108), GISTI, 2016, p. 35-38

- ^ United States. Central Intelligence Agency, Daily Report, Foreign Radio Broadcasts, Issues 11–15, 1967

- ^ "Congo Cities Get Back Old Names", Vancouver Sun, May 3, 1966, p.11

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Joe Trapido, "Kinshasa's Theater of Power Archived 17 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine", New Left Review 98, March/April 2016.

- ^ "DR Congo election: 17 dead in anti-Kabila protests Archived 16 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine", BBC, 19 September 2016.

- ^ Merritt Kennedy, "Congo A 'Powder Keg' As Security Forces Crack Down On Whistling Demonstrators Archived 17 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine", NPR, 21 December 2016.

- ^ PhD, Gutu Kia Zimi (10 January 2021). Growing Trees in Urban Kinshasa: Shrub Vegetation in Residential Plots in Kinshasa. Bloomington, Indiana, United States: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-6655-1262-6. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Iyenda, Guillaume (2007). Households' Livelihoods and Survival Strategies Among Congolese Urban Poor: Alternatives to Western Approaches to Development. Edwin Mellen Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7734-5269-5. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kinyamba, S. Shomba; Nsenda, F. Mukoka; Nonga, D. Olela; Kaminar, T.M.; Mbalanda, W. . (2015). "Monographie de la ville de Kinshasa" (PDF) (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Institut Congolais de Recherche en Développement et Etudes Stratégiques (ICREDES). pp. 9–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Wachter, Sarah J. (19 June 2007). "Giant dam projects aim to transform African power supplies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Redwood, Mark, ed. (16 May 2012). Agriculture in Urban Planning: Generating Livelihoods and Food Security. Thames, Oxfordshire United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-136-57205-0. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Congo Republic Energy Policy, Laws and Regulations Handbook - Strategic Information and Basic Laws. Miami, Florida, United States: Global Pro Info USA. 22 November 2017. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-5145-1238-8. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Kitambo, Benjamin; Papa, Fabrice; Paris, Adrien; Tshimanga, Raphael M.; Calmant, Stephane; Fleischmann, Ayan Santos; Frappart, Frederic; Becker, Melanie; Tourian, Mohammad J.; Prigent, Catherine; Andriambeloson, Johary (12 April 2022). "A combined use of in situ and satellite-derived observations to characterize surface hydrology and its variability in the Congo River basin". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 26 (7): 1857–1882. Bibcode:2022HESS...26.1857K. doi:10.5194/hess-26-1857-2022. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived from the original on 2 May 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Michael, Mukendi Tshibangu; Henri, Mbale Kunzi; Meti, Ntumba Jean; Felicien, Lukoki Luyeye (15 May 2020). "Floristic Inventory of Invasive Alien Aquatic Plants Found in Malebo Pool in Congo Rivers, Kinshasa, DR. Congo (Case of MOLONDO, MIPONGO, and JAPON Islands)". Global Journal of Science Frontier Research. 20 (C6): 31–44. ISSN 2249-4626. Archived from the original on 2 May 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Monographie de la province du Maniema (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: République démocratique du Congo, Ministères de l'agriculture et de l'élevage. 1998. p. 9. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ African Soils: Volumes 16-18. Paris, France: Commission Scientifique, technique et de la recherche de l'Organisation de l'unité Africaine. 1971. p. 169. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jean Flouriot, "Kinshasa 2005. Trente ans après la publication de l’Atlas de Kinshasa Archived 17 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine", Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer 261, January–March 2013; doi:10.4000/com.6770.

- ^ Luce Beeckmans & Liora Bigon, "The making of the central markets of Dakar and Kinshasa: from colonial origins to the post-colonial period”; Urban History 43(3), 2016; doi:10.1017/S0963926815000188.

- ^ a b c Innocent Chirisa, Abraham Rajab Matamanda, & Liaison Mukarwi, "Desired and Achieved Urbanisation in Africa: In Search of Appropriate Tooling for a Sustainable Transformation”; in Umar Benna & Indo Benna, eds., Urbanization and Its Impact on Socio-Economic Growth in Developing Regions; IGI Global, 2017, ISBN 9781522526605; pp. 101–102.

- ^ Commission Électorale Nationale Indépendante. "La Cartographie Electorale des 26 Provinces—Kinshasa". www.ceni.cd (in French). Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Climate: Kinshasa". AmbiWeb GmbH. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "KINSHASA, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "STATIONSNUMMER 64210" (PDF). Danish Meteorological Institute. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "LE PARC – Parc de la Vallée de la N'sele". parcdelavalleedelansele.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Driving directions to Jardin Zoologique, 1 Avenue Kasa-Vubu, Kinshasa". Waze. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Memoire Online – Tfc: inventaire dendrométrique et floristique des arbres du jardin botanique de Kinshasa – Samuel ABANDA". Memoire Online. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Friends of Bonobos | We save bonobos and their Congo rainforest home". Bonobos. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ a b Bédécarrats, Florent; Lafuente-Sampietro, Oriane; Leménager, Martin; Lukono Sowa, Dominique (2019). "Building commons to cope with chaotic urbanization? Performance and sustainability of decentralized water services in the outskirts of Kinshasa". Journal of Hydrology. 573: 1096–1108. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.07.023.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Gianluca Iazzolino, "Kinshasa, megalopolis of 12 million souls, expanding furiously on super-charged growth Archived 9 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine"; Mail & Guardian Africa, 2 April 2016.

- ^ Hoornweg, Daniel; Pope, Kevin (2017). "Population predictions for the world's largest cities in the 21st century". Environment and Urbanization. 29 (1): 195–216. Bibcode:2017EnUrb..29..195H. doi:10.1177/0956247816663557.

- ^ "Populations of 150 Largest Cities in the World". World Atlas. 7 March 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Nadeau, Jean-Benoit (2006). The Story of French. St. Martin's Press. p. 301; 483. ISBN 9780312341831.

- ^ Trefon, Theodore (2004). Reinventing Order in the Congo: How People Respond to State Failure in Kinshasa. London and New York: Zed Books. p. 7. ISBN 9781842774915. Archived from the original on 30 December 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2009. A third factor is simply a demographic one. At least one in ten Congolese live in Kinshasa. With its population exceeding eleven million, it is the second-largest city in sub-Saharan Africa (after Lagos). It is also the second-largest French-speaking city in the world, according to Paris (even though only a small percentage of Kinois speak French correctly),

- ^ Manning, Patrick (1998). Francophone sub-Saharan Africa: Democracy and Dependence, 1985–1995. London and New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 9780521645195. Retrieved 31 May 2009.[permanent dead link] While the culture is dominated by the Francophonie, a complex multilingualism is present in Kinshasa. Many in the francophonie of the 1980s labelled Zaïre as the second-largest francophone country, and Kinshasa as the second-largest francophone city. Yet Zaïre seemed unlikely to escape a complex multilingualism. Lingala was the language of music, of presidential addresses, of daily life in government and in Kinshasa. But if Lingala was the spoken language of Kinshasa, it made little progress as a written language. French was the written language of the city, as seen in street signs, posters, newspapers and in government documents. French dominated plays and television as well as the press; French was the language of the national anthem and even for the doctrine of authenticity. Zairian researchers found French to be used in vertical relationships among people of uneven rank; people of equal rank, no matter how high, tended to speak Zairian languages among themselves. Given these limits, French might have lost its place to another of the leading languages of Zaïre – Lingala, Tshiluba, or Swahili – except that teaching of these languages also suffered from limitations on its growth.

- ^ "XIVe Sommet de la Francophonie". OIF. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ "Kinshasa : Daniel Bumba a pris officiellement les commandes de la ville". Actualite.cd (in French). 21 June 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Pain (1984), p. 56.

- ^ "UN beefs up peacekeeping force in DR Congo capital Archived 13 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine", East African / AFP, 19 October 2016.

- ^ "US Ambassador: UN Aiding 'Corrupt' Government in Congo Archived 31 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine", VOA News, 29 March 2017.

- ^ Terry M. Mays, Historical Dictionary of Multinational Peacekeeping, Third Edition; Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2011; p. 330.

- ^ "UN troops open fire in Kinshasa Archived 10 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine", BBC, 3 June 2004.

- ^ Inge Wagemakers, Oracle Makangu Diki, & Tom De Herdt, "Lutte Foncière dans la Ville: Gouvernance de la terre agricole urbaine à Kinshasa Archived 18 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine"; L’Afrique des grands lacs: Annuaire 2009–2010.

- ^ Inge Wagemakers & Jean-Nicholas BCH, "Les Défis de l’Intervention: Programme d'aide internationale et dynamiques de gouvernance locale dans le Kinshasa périurbain Archived 18 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine"; Politique africaine 2013/1 no. 129; doi:10.3917/polaf.129.0113.

- ^ "IMF revises Congo's 2022 growth up to 8.5%, rebel conflict a concern". Reuters. 15 February 2023. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ a b "IMF Staff Concludes Visit to the Democratic Republic of the Congo". IMF. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ a b "La situation économique de la RD Congo en 2022 – Perspectives 2023". Direction générale du Trésor. 27 April 2023. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "Kinshasa – national capital, Democratic Republic of the Congo". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Emizet Francois Kisangani, Scott F. Bobb, "China, People's Republic of, Relations with"; Historical Dictionary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2010; pp. 74 Archived 1 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine–75.

- ^ Nuah M. Makungo, "Is the Democratic Republic of Congo being Globalized by China? The Case of Small Commerce at Kinshasa Central Market Archived 17 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine", Quarterly Journal of Chinese Studies 2(1), 2012.

- ^ "Cefacongo.org". Cefacongo.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "Onze school". Prins van Luikschool Kinshasa. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Collection_Congo_ Art: School Alhadeff". www.collectioncongo-art.nl. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ [1] UNESCO :The Congo Literacy Project (The Democratic Republic of Congo)

- ^ "Provincial Health Division of Kinshasa" Archived 14 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine African Development Information Services

- ^ Cybriwsky, Roman Adrian (23 May 2013). Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-248-9. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Morgan, Andy (9 May 2013). "The scratch orchestra of Kinshasa". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ CNN Archived 11 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Dedicated followers of fashion: Congo’s designer dandies Mark Tutton, CNN 13 February 2012

- ^ Bill Freund, "City and Nation in an African Context: National Identity in Kinshasa”; Journal of Urban History 38(5), 2012; doi:10.1177/0096144212449141.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ‘‘Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices’’, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 777

- ^ "Les travaux de construction de la Maison d'Adoration Nationale en bonne progression !". 20 May 2021. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ [Statistica: Africa Press Freedom https://www.statista.com/statistics/1221101/press-freedom-index-in-africa-by-country/ Archived 22 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine]

- ^ "Democratic Republic of Congo country profile – Media". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ "Countries: Democatric Republic of the Congo: News" (Archive). [sic] Stanford University Libraries & Academic Information Resources. Retrieved on 28 April 2014.

- ^ Nzuzi (2008), p. 14.

- ^ Aurélie Fontaine, "Housing: Kinshasa is for the rich”; Africa Report 5 May 2015.

- ^ "Trans urbain kinshasa". Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Request a ride in Kinshasa via the Yango app!". Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Flightera.net". 21 August 2022. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ "N'djili Airport website". Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "DRC Unveils $956 Million Plan to Modernize Matadi-Kinshasa Railway – Efficacy News". efficacynews.africa. 21 February 2024. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ^ Jonny Hong, "Gang crime threatens the future of Congo's capital", Reuters, 19 June 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Dept. of State – Congo, Democratic Republic of the Country Specific Information". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Bruce Baker. "Nonstate Policing: Expanding the Scope for Tackling Africa's Urban Violence" (PDF). Africacenter.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ a b O. Oko Elechi and Angela R. Morris, “Congo, Democratic Republic of the (Congo-Kinshasa)”; in Mahesh K. Nalla & Graeme R. Newman (eds.), Crime and Punishment around the World, Volume 1: Africa and the Middle East; Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2010; pp. 53–56.

- ^ [2] BBC News - 'Hell behind bars' - life in DR Congo's most notorious jail

- ^ Prisons in the Democratic Republic of Congo Archived 18 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, ed. Ryan Nelson, Refugee Documentation Center, Ireland; May 2002.

- ^ Manson, Katrina (22 July 2010). "Congo's children battle witchcraft accusations". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "Street Children in Kinshasa". Africa Action. 8 July 2009. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "A night on the streets with Kinshasa's 'child witches'". War Child UK – Warchild.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "Danballuff – Children of Congo: From War to Witches(video)". Gvnet.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "Africa Feature: Around 20,000 street children wander in Kinshasa". English.people.com.cn. 1 June 2007. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "Prevalence, Abuse & Exploitation of Street Children". Gvnet.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ "At the centre – Street Childrens". streetchildrenofkinshasa.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Ross, Aaron (13 March 2016). "Beaten and discarded, Congo street children are strangers to mining boom". reuters.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ "What Future? Street Children in the Democratic Republic of Congo: IV. Background". hrw.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Camille Dugrand, “Subvertir l’ordre? Les ambivalences de l’expression politique des Shégués de Kinshasa”; Revue Tiers Monde 4(228), 2016; doi:10.3917/rtm.228.0045. "Figures incontournables de l’urbanité kinoise, les Shégués ont fait l’objet de plusieurs travaux scientifiques (Biaya, 1997, 2000; De Boeck, 2000, 2005; Geenen, 2009)."

- ^ "Brussels". efus.eu. European Forum for Urban Security. 21 January 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Ankara". Ankara.bel.tr. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Congolese Culture". Friends of the Congo. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Ali, Muhammad (24 October 1999). "Muhammad Ali Remembers the Rumble in the Jungle". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Yocum, Thomas (15 October 2014). "Forty years on from the Rumble in the Jungle, Kinshasa is a city of chaos". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Erenberg, Lewis A. (22 May 2019). The Rumble in the Jungle: Muhammad Ali and George Foreman on the Global Stage. Chicago, United States: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226059570. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Catsoulis, Jeannette (9 June 2011). "'Viva Riva!'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (9 November 2017). "Félicité review – gritty story of Kinshasa bar singer". the Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ [3] Archived 16 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Rotten Tomatoes Season 1 The Widow 8 July 2019

- ^ Mujula, Fiston Mwanza (7 January 2016). "Tram 83, the Congolese novel that's wowing the literary world – extract". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2023.